- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

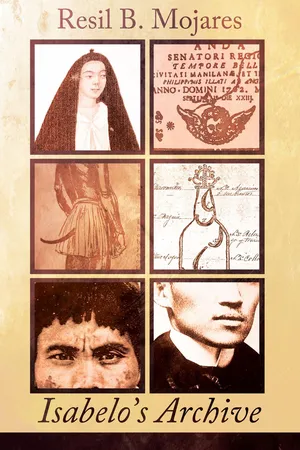

Isabelo's Archive

About this book

Isabelo's Archive reenacts El Folk-Lore Filipino (1889), Isabelo de los Reyes's eccentric but groundbreaking attempt to build an "archive" of popular knowledge in the Philippines.

Inspired by Isabelo's ghostly project, this collection mixes essays, vignettes, extracts, and notes on Philippine history and culture... Blending the literary and the academic, wondrously diverse in its range, it has many gems to offer the reader.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Publisher

Anvil Publishing, Inc.eBook ISBN

9789712729270Topic

HistoireNotes

Isabelo’s Archive

This is a revised version of a paper first published in The Cordillera Review, I:1 (2009), 105–120.

1. El Comercio (21 March 1885), n.p., datelined “Malabon, March 19, 1885.” I have not found a copy of the March 15 letter cited by Isabelo (El Comercio does not have an issue on this day, a Sunday; it may have appeared in another paper). The March 21 letter in El Comercio is reprinted in Jaime C. de Veyra & Mariano Ponce, Efemerides Filipinas (Manila: Imprenta y Libreria de I.R. Morales, 1914), 278–83.

De los Reyes wrote about this appeal in El Folk-Lore Filipino (Manila: Tipografia de Chofre y Cia., 1889), I:12–18. The first volume of this work was translated into English by Salud C. Dizon & Maria Elinora P. Imson and published by the University of the Philippines Press in 1994.

Two important essays have been written on this subject: William Henry Scott, “Isabelo de los Reyes, Father of Philippine Folklore,” Cracks in the Parchment Curtain and Other Essays in Philippine History (Quezon City: New Day Publishers, 1982), 245–65; Benedict Anderson, “The Rooster’s Egg: Pioneering World Folklore in the Philippines,” Debating World Literature, ed. C. Prendergast (London: Verso, 2004), 197–213; first published in New Left Review, 2 (March/April 2000). Also see Resil B. Mojares, Brains of the Nation: Pedro Paterno, T.H. Pardo de Tavera, Isabelo de los Reyes, and the Production of Modern Knowledge (Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2006).

2. On del Pan: Enciclopedia Universal Ilustrada Europeo-Americana (Bilbao: Espasa-Calpe, 1920), XLI:635–36. On Isabelo’s journalism: Megan C. Thomas, “Isabelo de los Reyes and the Philippine Contemporaries of La Solidaridad,” Philippine Studies, 54:3 (2006), 381–411.

3. Catalogo de la Exposicion General de las Islas Filipinas (Madrid: Est. Tipografico de Ricardo Fe, 1887), 584, 589. For examples of these articles, signed by Isabelo de los Reyes or “R,” see La Oceania Española (13 January 1885), 3; (15 January 1885), 3; (17 February 1885), 2; (12 March 1885), 3; (19 March 1885), 3; (22 March 1885), 3.

4. Alejandro Guichot y Sierra, Noticia Historica del Folklore. Origenes en todos los paises hasta 1890; desarrollo en España hasta 1921 (Sevilla: Hijos de Guillermo Alvarez, 1922), which has a brief account of Isabelo de los Reyes and folklore studies in the Philippines. I thank Michael Cullinane for a copy of the book.

Also see Sabas de Hoces Bonavilla, “Demofilo, ese desconocido,” Revista de Folklore, I:7 (1981), 23–30; Salvador Rodriguez Becerra, “El Folklore, Ciencia del Saber Popular, Historia y Estado Actual en Andalucia,” Revista de Folklore, 19:225 (1999), 75–80.

Antonio Machado y Alvarez was the father of the great Spanish poet Antonio Machado y Ruiz (1875–1939), whose views on literature and culture trace ideas similar to Isabelo’s. See James Whiston, Antonio Machado’s Writings and the Spanish Civil War (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 1996).

5. In this article, “Terminologia del Folk-Lore,” Isabelo comments on whether folk-lore is a science or not, citing such British folklorists as George Laurence Gomme, Edwin Sidney Hartland, and Alfred Nutt. Clearly, he did not see himself as a mere informant but a contributor to the “theory” of the field. The article is reprinted in de los Reyes, Folk-Lore Filipino, I:20–27.

6. See Guichot, Noticia Historica, 165–166.

7. Enciclopedia Universal, XXI:450–51.

8. On the domestic situation in Spain: C.A.M. Hennesy, The Federal Republic in Spain (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1962), 53–56, 210–11; Enric Ucelay da Cal, “The Nationalisms of the Periphery: Culture and Politics in the Construction of National Identity,” Spanish Cultural Studies, ed. H. Graham & J. Labanyi (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), 32–39.

9. Christopher Schmidt-Nowara, The Conquest of History: Spanish Colonialism and National Histories in the Nineteenth Century (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2006), 55; Antonio Feros, “‘Spain and America: All is One’: Historiography of the Conquest and Colonization of the Americas and National Mythology in Spain, c.1892–c.1992,” Interpreting Spanish Colonialism: Empires, Nations, and Legends, ed. C. Schmidt-Nowara & J.M. Nieto-Phillips (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2005), 109–34.

10. Guichot, Noticia Historica, 166.

11. In historiography, this impulse is illustrated in Manila Spaniard Ricardo de Puga’s lament on the lack of a modern historia general of Spain and her territories. Criticizing the fragmented, localistic character of existing cronicas and historias, he calls for integrating the histories of “different kingdoms” in the creation of “Spanish nationality” (nacionalidad Española). See R. de Puga, “Reflecsiones acerca de las publicaciones historicas relativas a Filipinas,” Ilustracion Filipina, II:13 (1 July 1860), 150. II:6 (15 June 1859) – II:13 (1 July 1860).

12. Antonio de Morga, Sucesos de las Islas Filipinas… anotada por Jose Rizal (Paris: Libreria de Garnier Hermanos, 1890). Facs. ed. published in Manila in 1961; English ed., 1962.

13. Pedro A. Paterno, La Antigua Civilizacion Tagalog (Madrid: Tipografia de Manuel G. Hernandez, 1887), Los Itas (Madrid: Imprenta de los Sucesores de Cuesta, 1890), El Barangay (Madrid: Imprenta de los Sucesores de Cuesta, 1892), La Familia Tagalog en la Historia Universal (Madrid: Imprenta de los Sucesores de Cuesta, 1892), and El Individuo Tagalog (Madrid: Sucs. de Cuesta, 1893). The last three-mentioned works appeared as a single volume entitled Los Tagalog (Madrid: Sucesores de Cuesta, 1894).

14. Isabelo de los Reyes, Las Islas Visayas en la epoca de la conquista (Iloilo: Imprenta de “El Eco de Panay,” 1887), Historia de Filipinas: Prehistoria de Filipinas (Manila: Imprenta de D. Esteban Balbas, 1889), Historia de Ilocos (Manila: Establecimiento Tipografica de “La Opinion,” 1890), 2 vols.

15. Robert Darnton, “Philosophers Trim the Tree of Knowledge: The Epistemological Strategy of the Encyclopedie,” The Great Cat Massacre and Other Episodes in French Cultural History (New York: Basic Books, 1999), 191–213.

16. See Jacques Derrida, Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression, trans. E. Prenowitz (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995), 4n. Also Michel Foucault, The Archaeology of Knowledge and the Discourse on Language, trans. A.M. Sheridan Smith (New York: Pantheon, 1972), 126-31; Sandhya Shetty & Elizabeth Jane Bellamy, “Postcolonialism’s Archive Fever,” Diacritics, 30:1 (2000), 25–48.

17. Juan Goytisolo, State of Siege, trans. H. Lane (London: Serpent’s Tail, 2003), 94, 97, 116.

18. See, for instance, Catherine Gallagher, “Counterhistory and the Anecdote,” Practicing New Historicism, ed. C. Gallagher & S. Greenblatt (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000), 49–74.

19. Jorge Luis Borges, “The Book of Sand,” The Book of Sand and Shakespeare’s Memory, trans. A. Hurley (London: Penguin Books, 1998), 89–93.

20. There was in the Spanish folklore movement a basic contradiction not quite resolved in the stress on “the people” and the bourgeois intellectualist bias for systematization and modernization, a contradiction to be found in Isabelo as well. See Mojares, Brains of the Nation, 313–31; Ignacio R. Mena-Cabezas, “Recepcion y Apropriacion del Folklore en un Contexto Local: Cipriana Alvarez Duran en Llerena (Badajoz),” Revista de Folklore, 23:271 (2003), 6–15.

21. Isabelo de los Reyes, Filipinas. Independencia y Revolucion (Madrid: Imp. y Lit. de Jose Corrales, 1900), 118–36.

The Haze of History

1. Antonio Pigafetta, The First Voyage Around the World, ed. T.J. Cachey, Jr. (New York: Marsilio, 1995), 67–68. While its exact location has not been determined, Kipit (Ch...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Isabelo’s Archive

- The Haze of History

- Maidens Shrouded in Darkness

- A Woman Named Virgin Mary

- Men With Tails

- A History of Shame

- Remembering the Body

- Densities of Time

- Dragon and Leech

- A Poem of All the Names of the Rivers

- National Geographics

- The Verses of Bartolome Saguinsin

- The Aritmetica of Rufino Baltazar

- The Book That Did Not Exist

- Unicorns in the Garden of Reason

- Isabelo’s Almanac

- History of the World in Seventeen Lines

- Blumenbach’s Model

- Claiming “Malayness”

- Tales of Manilamen

- The Traveling Filipino

- The Itineraries of Mariano Ponce

- Atlas Versified

- Ilocanizing Verdi

- Notes for the Production of a Brechtian Komedya

- Musica Moralia

- Jose Rizal and the Invention of a National Literature

- The Mysteries of Gabriel Beato Francisco

- Canonizing Balagtas

- The Making of a National Pantheon

- Beheading Heads, Changing Heads

- The Dangerous Beauty of the Headhunter

- Broken Branches

- Illustration Credits

- Notes

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Isabelo's Archive by Resil B. Mojares in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Histoire & Théorie et critique de l'histoire. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.