![]()

Contingents of the Leibstandarte assemble as their Führer’s Guard of Honour during the Nuremberg Rally of 1937, notable for Hitler’s assurance that the Third Reich would last for 1000 years.

CHAPTER ONE

FOUNDATION

After her defeat in World War I, Germany was ripe for revolution, with various gangs fighting for power on the streets. Cocooned by bodyguards and followers addicted to ongoing violence, Adolf Hitler sought protection in the creation of a new elite, the Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler.

Newsreel propaganda films produced in Nazi Germany during the life of the Third Reich featured footage of elite members of Heinrich Himmler’s Schutzstaffel (SS Protection Squad), immaculate in their black and silver uniforms, standing like robots before the Berlin Reich Chancellery. These were the troops of the Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler, responsible for the safety of their Führer, a bodyguard contingent destined to rise under the clash of arms to become the premier panzer division of the Waffen-SS.

Those who served in the Leibstandarte and in the armed SS as a whole enjoyed a special status and glamour, the remnants of which, even amid the ashes of defeat, the dwindling number of veterans are keen to preserve. There is some justification for this. The armed echelons of the Schutzstaffel, with their double-S runic sleeve flash and belt buckles inscribed with the motto Meine Ehre heisst Treue (‘My Honour Is Loyalty’) fought with considerable bravery on the front line during World War II. What this does not take into account, however, and what apologists to this day conveniently ignore, are the many crimes of brutality which can be laid directly at the door of the Leibstandarte.

ORIGINS

To reach the truth means taking a look beyond the popular image of the immaculate uniforms and marching bands of these SS paragons. The origins lie deep in a Germany still in the shadow of the 11th day of the 11th month of the year 1918. Kaiser Wilhelm II, who had vainly intended to abdicate only as German Emperor, but still retain his rights as King of Prussia, had finally taken his withered arm and shattered imperial ambitions into exile. For the army, rich in the traditions of battle triumphs stretching back to the days of Frederick the Great, there was a legacy of shame and submission at its enforced emasculation by the victors, following the Treaty of Versailles. But for many whose husbands, brothers and sons had perished on the battlefields of France and Flanders, there was weary resignation and a longing to be rid of militarism. There was little sympathy for those that found the Allied terms unacceptable and even less for the notion that, in the words of Philipp Scheidemann, first Chancellor of the Weimar Republic, the ‘hand should wither’ before any shameful demands – ‘intolerable for any nation’ – were agreed by signature.

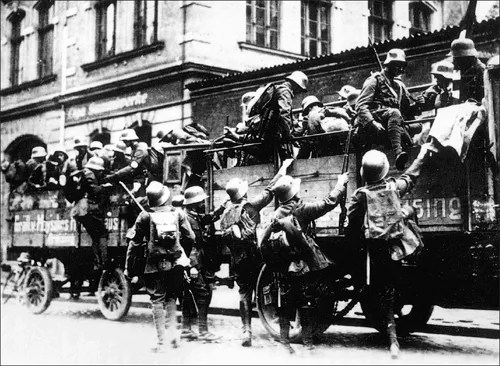

Members of the Freikorps dismount from lorries in post-war Berlin. The Freikorps was a right-wing organisation staffed by former soldiers, and a number were later to join Hitler’s Sturmabteilung, or SA.

Other voices of resentment and fury, however, drowned all calls for moderation. Mass meetings were held throughout the country which were ripe with sullen threat to national order. Aggression soon followed. Cities became minor battlefields – convenient areas of violence for a variety of terrorist groups such as the Spartacists, forerunner of the German Communist Party, and groups of ex-servicemen formed as the Stahlhelm and the Freikorps, who clashed with the manpower of the Reichswehr, the standing army acting as the Chancellor’s Guard. In Bavaria, a Soviet-style regime assumed power with an optimistic programme of land reform, workers’ control and participation in government. Although such heresies were defeated with consummate savagery, the legacy of Bavarian socialism was to be the birth of a new movement. Adolf Hitler, its chief architect, was fuelled by two hatreds: the teachings of Karl Marx and, above all, a loathing of Jews, whom he saw as ‘rats, parasites and bloodsuckers’.

During World War I, Hitler had served as a Lance Corporal (Gefreiter) in the 16th Bavarian Infantry (List Regiment). Before his discharge, he had attended one of the soldiers’ indoctrination classes with which the Reichswehr supplemented its armed combat of left-wing subversion. As a Bildungsoffizier (Instruction Officer), he received orders to investigate – in fact, spy on – a collection of nationalist veterans and beer-swilling nationalists, as well as general misfits, who made up the all but bankrupt Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (German Workers’ Party). The group certainly had some resonance for Hitler, especially where the fifth of its 25 Points was concerned: ‘None but members of the nation may be citizens of the state. None but those of German blood, whatever their creed, may be members of the nation. No Jew, therefore, may be a member of the nation.’

The future Führer joined as Party Member No. 555 and, by January 1920, had emerged as its leader. During the next month, in an impassioned speech held in a Munich beer hall, he demanded the adoption of all 25 points. He was already thinking ahead, however, and planning a far more radical programme, paramount to which was the demand that all Jews be denied office and citizenship. The name of the party was changed that April to National-sozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (the NSDAP, or National Socialist Party).

FOUNDATION

Before long came the call for a campaign of hate and subversion where blood would literally spill onto the streets of German towns and cities. In such dangerous times, none was exempt from the threat of violence, party leaders and would-be dictators least of all. Hence, in 1923, came the emergence of the Stabswache (Headquarters Guard), a pretentious name for the activities of its two leading strongmen, Joseph Berchtold, a stationer, and Julius Schreck, a chauffeur, both of whom were assigned a crude bodyguard role by Hitler. This pair were joined by several adherents who were, for the most part, labourers from the lower middle or working classes of Munich, the likes of Ulrich Graf, butcher by trade and amateur boxer by night; Emil Maurice, a watchmaker with a criminal record; and Christian Weber, a penniless former groom.

The Stosstrupp (Shock Troop) Adolf Hitler, which incorporated the Stabswache, at first consisted of some 30 thugs much addicted to punch-ups with opponents and the copious use of boots, knives, blackjacks and rubber truncheons. These toughs, many of them recruited from the Freikorps, in time became members of the infinitely more powerful Sturmabteilung (SA, or Storm Troopers). This was the creation of Freikorps leader Ernst Röhm, who built up a 2000-strong private army, boosted by Freikorps volunteers who became SA storm troopers. The original Stabswache, nevertheless, does deserve at least a footnote in the history of pre-war Germany, laying as it did the foundations for a force responsible solely to Hitler with the task of protecting him from all enemies, by whatever method and, if necessary, with individuals’ lives. The Leibstandarte of the future was to exist essentially for the same purpose.

On 9 November 1923, a crucial event took place, although few foresaw its repercussions at the time. In Munich, a 600-strong group of SA, led by Hitler, made an ill-judged bid to snatch power from the nationalist and rigidly independent leaders of Bavaria and proclaim a new government, in the so-called Beer Hall Putsch. This intended political coup was an embarrassing failure which degenerated into semi-farce, at a cost of around a dozen Stosstrupp lives, SA casualties and short-term imprisonment for Hitler. While Hitler languished in Landsberg jail, the various factions became even more fragmented and uncontrollable. On release, Hitler made up his mind. He had need for a single, cohesive protection force.

In April 1925, eight men came together to create a new Stabswache. Within two weeks, it had become the SS, destined to be controlled by the myopic Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler, the one-time industrial chemist who was dedicated to the pursuit of homeopathy, herbal cures and, most of all, dreams of a racially pure Germany. Even within the tight embrace of the SS, however, Hitler wanted the services of men who would be loyal to him exclusively, as he made clear in one of his countless dissertations:

‘Being convinced that there are always circumstances in which elite troops are called for, I created in 1922–23 “the Adolf Hitler Shock Troops”. They were made up of men who were ready for revolution and knew that some things would come to hard knocks. When I came out of Landsberg everything was broken up and scattered in sometimes rival bands. I told myself then that I needed a bodyguard, even a very restricted one, but made up of men who would be enlisted without conditions, even to march against their own brothers, only 20 men to a city (on condition that one counts on them absolutely) rather than a dubious mass … But it was with Himmler that the SS became an extraordinary body of men, devoted to an ideal, loyal to death.’

The Munich Putsch, 9 November 1923. The bespectacled figure with the Imperial Eagle flag is Heinrich Himmler, future Reichsfuhrer-SS and supreme chief of the Gestapo and the Waffen-SS, including the Leibstandarte.

DIETRICH THE BAVARIAN

Hitler had no intention of being saddled with a ‘dubious mass’. Less than two months after coming to power as Chancellor of the Reich in January 1933, he turned to an old party comrade and former bodyguard, Josef (familiarly known as ‘Sepp’) Dietrich, a strong-jawed, thick-accented Bavarian, and former artilleryman. That same year, in May, Dietrich was able to report to Hitler that he had formed a headquarters guard of loyal SS men titled the SS-Stabswache Berlin, conveniently quartered near the Reich Chancellery. Then came two more Stabswache incarnations, with two more successive changes of title. First, there was the SS-Sonderkommando Zossen (Special Commando), a designation which signified something of the guard’s elite character. Secondly, as a result of its merger with Sonderkommando Juterbog, it received first the title Adolf-Hitler-Standarte. Then, at the behest of Hitler himself, this was changed to Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler, (SS Bodyguard Regiment Adolf Hitler), a name chosen deliberately to prompt memories of the old Bavarian Life Guards.

The announcement of the name change was made on the last day of the Nazi Party rally held in the Luitpoldhalle at Nuremberg in September 1933, nine months after Hitler came to power. The ceremonial event, staged with all the elaborate spectacle that Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels could muster, carried the self-confident title ‘Congress of Victory’. Here, the towers of Kleig lights shone on 60,000 Hitler Youth, parading with the slogans of ‘Blood and Honour’ and ‘Germany Awake’. At the rear of the stage was the German eagle, its talons enclosing the golden laurel-wreathed swastika, and beneath which stood 60 stalwarts of the SS in their uniforms of black and silver, their dress swords drawn and shouldered.

Once Hitler had arrived precisely at 17:00 hours, flanked by Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler and Reinhard Heydrich, head of the Reich Central Security Office, he took his place on his podium. The spectators were then treated to a lengthy, bombastic speech lasting over an hour, the overall theme of which was ‘the reward of virtue’ (Turgenheld). Deserving of such rewards, Hitler made clear, were those who had kept the faith, not only with him personally, but also to the ideals of Germany and National Socialism. Keeping that faith had meant conducting a ceaseless, ruthless campaign against treachery, wherever it was manifest. Special tribute was paid to Heinrich Himmler – ‘my Ignatius Loyola’ – and to those who served with him, Hitler’s faithful guards, his Stabswache. It was to be their reward to have a special name created for them, ‘a name indelibly ...