![]()

1

All escape and evasion is a battle of minds, yours against your opponent’s. Try to imagine yourself in the enemy’s position, and use all your intelligence to stay one step ahead.

Hiding and Evading

Hiding and evading is a test of nerve, intelligence and skil, and demands a high level of mental stamina. The central point is to consider the implications of every action before making it.

Although most modern military forces provide training in prisoner of war (POW) survival, it is obviously far more advisable to avoid capture in the first place. The conditions in which soldiers are likely to fall prisoner change according to the nature of the conflict. During major set-piece battles, such as those which took place during World War II, soldiers are most likely to be captured en masse when their unit is outmanoeuvred or outfought by the enemy. In June 1941, for example, some 287,000 Soviet soldiers became prisoners after they were encircled by the German Army Group Centre during the battle of Bialystok–Minsk, just one of several strategic disasters that threatened to overwhelm the Soviet Union during Operation Barbarossa. No conflict since 1945 has matched World War II for its scale of captives, but the Indochina War (1945–54), Vietnam War (1963–75), Indo–Pakistan War (1971), Iran–Iraq War (1980–88) and the 1991 Gulf War all saw substantial prisoner counts following conventional engagements.

On an individual level, there is often little a soldier can do to prevent capture if his unit is encircled and disarmed. In some instances, pretending to be dead has merit, especially if an enemy is moving quickly and will not hang around to consolidate ground. During the airborne component of the D-Day landings in June 1944, US soldier John Steele of the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment snagged his parachute on the church tower in the centre of Sainte-Mère-Église, France. Even though the town was bustling with Germans, Steele hung there silently, as if dead, and did so until the Germans pulled out the next day and the town fell into American hands. Such an approach has its risks. If an enemy soldier has an inkling that someone is feigning death, he is more likely to put a bullet or bayonet into the body than inspect closely. For these reasons, it is often far better to find a good hiding place (see below for recommendations), and wait until nightfall to move and cross friendly lines.

Threat Levels

Soldiers moving into potentially hostile areas must maintain constant awareness of potential and actual threats. In this scenario, the absence of children and women on the street should give cause for concern, as should the figure in the background, watching over the wall. This individual could be a hostile observer, monitoring his enemy’s patrol movements in preparation for a possible ambush or kidnap attempt.

Basic Precautions

In the context of modern counter-insurgency warfare, more personal threats to liberty have arisen. Terrorist factions and insurgent groups can extract dark publicity from the capture of just one enemy soldier. On Sunday 25 June 2006, Corporal Gilad Shalit of the Armor Corps, Israel Defence Forces (IDF), was kidnapped by members of the Palestinian militant organization Hamas, following a raid on an Israeli outpost in the southern Gaza Strip. (Two other IDF soldiers were killed, and three wounded.) At the time of writing (2011), Shalit was still in captivity, his vulnerable position used as a political bargaining chip in the troubled region.

British Army Tip: Kidnapping

For small military units conducting patrols, manning checkpoints or outposts, mounting raids and performing general peacekeeping, there are common ingredients in many kidnap situations:

• Small units become lost within urban or remote rural areas, primarily through navigational errors or having to follow detours because of unexpected obstructions or troublesome terrain.

• Soldiers manning outposts or checkpoints are too few in number to make a convincing defence, and are often isolated from reinforcements.

• Units have to travel regularly along particularly dangerous routes, in areas where the rule of law is weak and insurgent groups dominate the local population.

• Kidnappings can sometimes involve local people known to the prisoners; certain individuals can feign friendship, while at the same time leading soldiers into compromising situations.

• Getting caught in an ambush – many kidnappings happen opportunistically, when a soldier or small unit is isolated during an ambush or improvised explosive device (IED) attack.

• A vehicle is disabled, either through an ambush or because of mechanical failure, leaving those aboard stranded in a single, vulnerable location while they wait for assistance.

• Special forces soldiers, through their common repurposing as VIP bodyguards, are all too aware of these factors, and so have developed a rigorous set of tactical behaviours that dramatically lessen the chances of being kidnapped in the first place. We will look at some of these rules in this chapter, before turning to explore in detail the fundamental techniques of evasion on the ground.

With the ongoing deployments of Western forces in Afghanistan and Iraq, kidnap awareness training has become critical, albeit erratically distributed. Such training focuses on key techniques and tactical policies to reduce the chances of being taken prisoner.

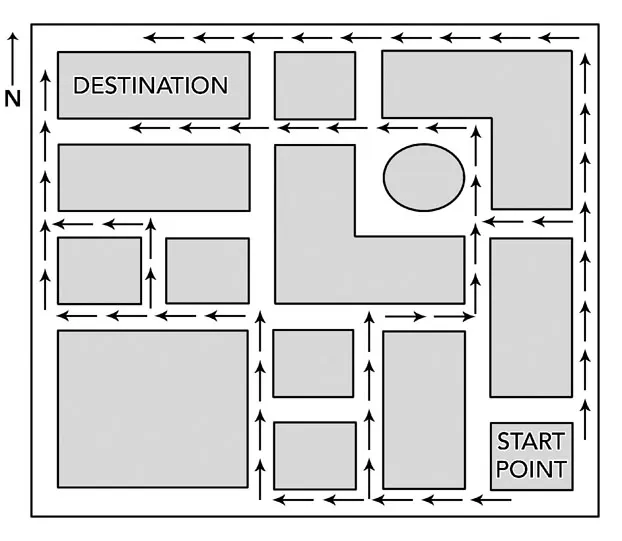

Varied Routes

For military units moving regularly between fixed destinations in hostile territory, it is imperative to vary the journey regularly and inventively, to prevent the enemy identifying a predictable route along which they can set up an ambush.

Iraq Kidnapping, 2007

On 29 May 2007 in Baghdad, at 11:50 (local time), five British nationals were kidnapped by Iraqi militants in Baghdad. The kidnapping was not the first in the country since the invasion of 2003, but its circumstances set alarm bells ringing amongst the security community. The incident did not occur on an isolated rural road or in an enemy-held urban zone, but in the Finance Ministry building in east Baghdad. Nor were the victims all amateurs – four of them were ex-military working as bodyguards and security personnel (the other man was a local IT consultant). Eyewitness accounts revealed that the militants arrived in force – possibly up to 100 men – most dressed in police and military uniforms and carrying authentic documentation (they were led by what appeared to be a police major). They entered the building, bursting into a lecture room and shouting ‘Where are the foreigners?’ Once a group of Westerners were identified, they were overwhelmed, bundled into a van and taken away for a long period of captivity. The four security guards were eventually executed, while the IT consultant was freed. A sixth man, another IT consultant, avoided kidnapping by hiding under floorboards during the initial attack.

Vary your route, vary your times

Insurgents and terrorist groups thrive on predictability. If, for example, they know that a military supply convoy travels along a main road between two cities every weekday morning at 08:30–09:30, they are able to plan and coordinate the most efficient attack possible, based on days of observational intelligence. For this reason, in contested areas foot patrols or vehicular units have to vary their routes of travel on a daily basis, to avoid forming any regular patterns of movement of which the enemy can take advantage. Times of travel must also change regularly – military bases are often under enemy watch, and insurgents can report predictable times of departure to ambush or pursuit groups. Good knowledge of local threat areas is critical in all defensive route planning. Except on offensive operations, or if there is literally no choice, any route should avoid areas of particular danger – ie, those that have known heavy concentrations of enemy forces. If a high-threat route must be taken, a unit needs to make sure that it has the offensive firepower to handle itself in an attack.

Know your route

Getting lost is one of the most dangerous situations for a small unit in insurgent-dominated territory. Preparation is the key to preventing this situation. Each member of the patrol, especially the team leaders (officers and NCOs), should have a sound grasp of the overall area of operations (AO), including all its major and minor roads, bridges, rivers and streams,...