![]()

Chapter One

War and Cinema

Chapter I traces historical accounts happening prior to the outbreak of World War II and before the spread of motion pictures in Asia. Events narrated in this chapter may appear remote from the actual subject taken up in this book. They are, however, necessary in providing the background to explain the tragic wartime events and the role played by cinema in the Japanese occupation, themes that will be adequately discussed in subsequent chapters. No matter how distant and remote the geopolitical reasons which shaped Japan’s desire to dominate the region, this chapter’s detour provides a historical perspective essential to the understanding of Japan’s occupation of the Philippines and its use of motion pictures to achieve its colonial ambition.

The presence of Japanese settlers in the country was felt centuries prior to the military invasion in the 20th century. Whether engaging in maritime trade or fishing or fleeing from Christian persecution—several Japanese communities started to settle in the country while it was under Spanish colonial rule.1 While individual persons fancied transforming parts of the country into Japanese territories, no personal desires were fulfilled. It took the violent invasion by the Japanese Imperial Army to fulfill such dreams, although this army had higher ambitions than merely owning a few scattered islands. The Japanese military wanted to take control of the entire Philippine Islands, as it had done with its neighboring islands and territories.2 Fueling the desire to conquer its neighbors was Japan’s implicit political ambition to dominate the Asian region with the army’s much sought-after dream of establishing the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.3

The sudden Japanese invasion in 1941 caught those charged with the Philippine defense security unprepared. The U.S. air and naval forces stationed in the country were decimated by the surprise attacks of Japanese war planes. These allowed Japanese naval forces to land in various parts of the country without much resistance. To avoid a bloodbath, the combined U.S.-Filipino forces left the capital, Manila, with the plan to make a last stand in Bataan and Corregidor where, faced by a barrage of military attacks by the Japanese, the defense forces eventually surrendered to the Japanese occupation army, but only after a brave, although desperate, fight. With this defeat, the entire country also fell.

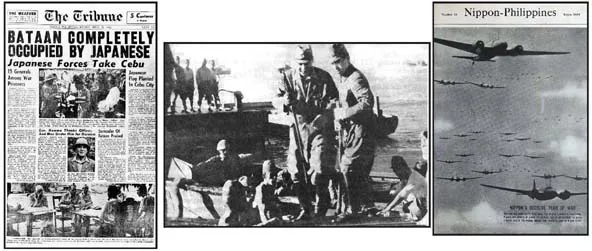

Propaganda newspaper Tribune (L), announced the Japanese occupation as Gen. Masaharu Homma landed with his troops in Lingayen on December 24, 1941. At far right, Japanese publication shows Japan’s flying fortress

Similarly affected by the arrival of the Japanese army was the infant local movie industry. Japanese occupation resulted in the untold devastation befalling the film community. Severe unemployment greeted hordes of movie workers after they lost their jobs when movie theaters, production studios, and distribution houses were shut down. Also lost were ancillary jobs dependent on the film industry. Local audiences were left viewing recycled and heavily censored films. The total decimation of the film business came with the liberation of Manila, when retreating Japanese soldiers and the invading U.S. army engaged in an orgy of destruction that left the city in ruins. Lost were movie theaters and studios, and more importantly, the lives of people working in the movie industry, bringing the entire movie business to its knees.

WINDS OF WAR OVER ASIA

The invasion of the Philippines by the Japanese Imperial Army may best be seen when the sequence of events leading to the war is viewed within the larger context of the geopolitics in Asia and the Pacific prior to the outbreak of World War II.4 The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii on December 7, 1941 prompted the U.S. to declare war against Japan. In hindsight, one could see this as a consequence of an earlier act of U.S. aggression, when American naval and military forces took over the Philippine Islands in 1898. This came after the war flotilla under the command of then-Commodore George Dewey invaded las islas Filipinas (later to become the Philippine Islands), a Spanish colony. This resulted in the Battle of Manila Bay which happened on May 1, 1898. 5

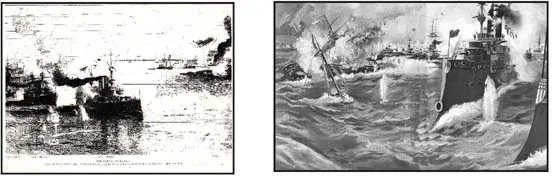

An illustration (L) and a painting (R) depict Cdr. George Dewey’s naval fleet defeating the Spanish armada in the Battle of Manila Bay

Events that took place in the country from the said naval conflict resulting to the ceding of the Philippine territory to the victorious Americans, and the earlier Western occupation of other Southeast Asian neighbors, did not escape the notice of Japanese observers, among which was the powerful Japanese Imperial Army. America’s foothold in the Pacific region raised alarm signals, as the U.S. manifested signs of joining older powers like England, France, Spain, Holland, and Portugal, among others, in partitioning the entire Asian continent into their respective colonial territories. A few decades earlier, Japan had its own brush with the American navy. In 1853, Commodore Matthew C. Perry forced the late Tokugawa Shogunate to sign a trade treaty with the U.S. This forcibly opened Japan to outside trade after centuries of isolationism. It also spelled the collapse of the shogunate and ultimately led to the country’s modernization. Now finding itself as a rising military power, this narrow strip of islands that had limited resources wanted to preserve the gains it made. Asserting its military strength in the region, Japan annexed nearby territories like Choson (present-day Korea), Formosa (present-day Taiwan), as well as Manchuria (in China) and parts of Russia.

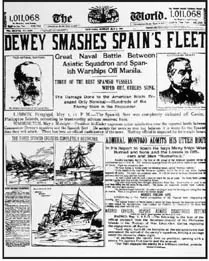

Cdr. Dewey’s naval success celebrated in U.S. newspaper

Japan’s imperialist impulse can be historically traced back to the Meiji Restoration of 1868, when feudalism was brought to an end. This epoch in Japan’s history unified the country. At the ideological center of the state’s governance was the emperor system. Much of the drive and ambition which Japan’s national leaders displayed while expanding their country’s territory was motivated by their allegiance to the emperor. Meiji leaders developed their own ideology for turning Japan into a major player in the world arena. They embarked upon what Akira Shimizu describes as “a policy of economic growth achieved by militarization, epitomized by the motto, ‘rich country, strong army (fukoku kyohei).’”6 The strong desire to modernize, as Shimizu avers, formed an ideological basis for Japan’s imperialist policy which, in years to come, would see Japan encroach on its neighboring territories. As Shimizu notes, “imperialism was seen as the only way toward progress and material enrichment.”7

Triumphant Japanese soldiers shout “Banzai!” At right stand wartime monarchs, Emperor Hirohito with Empress Nagako (a.k.a. Kojun) beside him

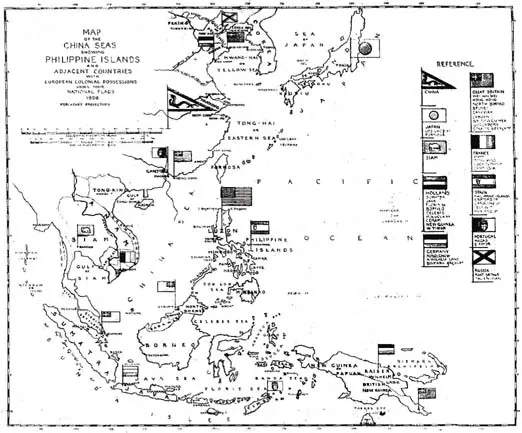

Given this ideological perspective, Japan looked at Asia as its potential domain that could be acquired with strong military action. This idea was further fueled by the fact that, one by one, countries in the region kept falling into the hands of Western imperialist powers. Hong Kong, India, and Singapore were under British rule; the Dutch East Indies (present-day Indonesia) was under the Dutch; Indochina (comprising of present-day Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos) was under the French; and the Philippines, in 1898, changed hands from Spanish to American rule. Asia appeared to be a plaything of Western colonial powers. Countries could be grabbed, owned, or bartered among Western colonizers. Japan, as history later shows, wanted to become a major player in the game.

In order to assure Japan’s own survival and to catch up with world powers, leaders of the Meiji era also looked towards Asia. They were brimming with ambition to one day have the country play a major role in the region’s transformation. What they needed to overcome was the Western colonial domination gripping the region then.

The veil of colonialism was cast across East and Southeast Asia as Western powers spread their territorial claims in countries this side of the continent

This intense desire to rule convinced Japan of its self-avowed moral right to wrestle Asian countries away from Western powers. Japan believed that if these Western powers were to continue exercising control over Asian countries, they would forever bear the yoke of colonization. Consequently, the threat of Japan getting subjugated one day by a Western power was a real one. As years went by, Japan’s ambition and drive found its realization in the overriding idea of the “Asian renaissance” (or “developing Asia”), an idea which hazarded the thought that if Asia were to be left alone, it would one day be completely dominated by England, France, Holland, and the new-kid-on-the-block, the U.S.

The promise of Japan leading Asia gained advocates in Japan’s Imperial court. Although it did make sense for the country to awaken its Asian neighbors from colonial domination, the idea of “developing Asia” served as an ideology guiding the invasion of countries in the region. When Japan finally took steps to free Asian countries from Western control, its invasion of those countries clearly revealed the real reason for its dastardly act—Japan’s own expansionist ambition.

The belief in “rich country, strong army (fukoku kyohei),” coupled with the ideology of “developing Asia,” elicited an imperialist attitude that led to Japan assuming a two-pronged strategy on how to achieve a unified Asia: the “northern-southern” policies of conquest. Shimizu describes these policies:

Japan had been vacillating a long time between the choice of the northern policy intending to advance into Siberia with the enemy being Soviet Russia, and the southern policy, chasing after the key commodities of South East Asia, which led to the expected friction with England, the U.S. and the Netherlands; finally advancing into the Southern Indochina was the first step of the fulfillment of the southern policy.8

The northern policy saw Japan overwhelming its enemies with the wars it waged against China, all through Manchuria and Russia. It provided Japan with the euphoric experience of becoming a world power. Japan’s success in this northern option achieved two climaxes: first, in the Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895), in which the military weakness of the Ching Empire gave Japan’s military the initial boost it needed; and second, in the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905), where Japan triumphed over Imperial Russia. There was, however, a deadlock in the war situation in China that compelled Japan to put into action its southern option. The policy to move southward in order to conquer the South Seas would have dire consequences for countries like the Philippines.

Japanese army advancing its troo...