![]()

Adolf Hitler, as Chancellor, bows to President von Hindenburg at a memorial service in Berlin in June 1934. Immediately on Hindenburg’s death Hitler merged the offices of Chancellor and President to become Der Führer.

CHAPTER ONE

BEGINNINGS

From the birth of his Nazi movement, Adolf Hitler set out to tap into a promising source of recruits in the various groups and societies associated with German youth. He appealed to the latent patriotism of a generation anxious to build a new Germany from the ruins of the old.

Germany has a rich tradition of organizations for youth. Over the decades, there have been groups with a variety of beliefs and persuasions, including Pfadfinder, or boy scout, organizations that promoted little beyond good fellowship and camp fire camaradie. At the end of World War II, apologists for Nazi Germany tended to link the Hitler Jugend, or Hitler Youth, with the scouting fraternity, suggesting that its activities were largely confined to competitive sports and country rambles.

This was certainly a view that newsreels and the Nazi propaganda machine were keen to encourage. But this was only part of the story. Soon after securing power in 1933, Hitler announced his intention to create a state in which strict obedience and discipline were mandatory with the harshest penalties being reserved for dissenters. There was to be a very specific role for German youth, who were be mustered as instruments of war. The Führer’s rousing call for a ‘Thousand Year Reich’ and his proclamation that, ‘He alone who owns the youth gains the future’, awoke a latent patriotism within the German people, who had till then been crippled by cynicism. A generation of youth was urging the rebirth of a Germany that had endured the twin fevers of political agitation and street violence during the Weimar Republic.

PATRIOTIC FERVOUR

At general mobilization in 1914, Germany had been gripped by a patriotic fervour and had faith in ultimate victory. In the Reichstag, differences had been set aside. Kaiser Wilhelm II, with his withered arm and imperial ambitions, had proclaimed triumphantly: ‘I see no parties any more, only Germans.’ By November, the German advance on the Western Front towards Paris had been halted on the Marne river. The German Fourth Army was given the order to cut through the defences that had been established by the Allies between Ypres and the Channel. The few regular soldiers in the Fourth Army were mainly young volunteers, many of them students and schoolboys who, with their last year at school remitted, had swarmed with enthusiasm to the colours. Typical of them was Walter Flex, a schoolteacher’s son, who declared: ‘We need a tough, hard-headed national idealism that is prepared for every sacrifice.’

Middle-class young men, impatient with politicians and theorists, believed firmly that victory in the war would be seized by them, rather than a fumbling older generation. Indeed, the potent idealism of Flex’s contemporaries, who rejected the rhetoric of both Left and Right, had already led to the foundation of the German youth movement dedicated to freedom, embodied by the Wandervogel, or ‘Birds of Passage’, organization. Followers emphasized the rediscovery of nature, a rejection of materialism and an awareness of pre-industrial ways of life. Members were keen to adopt an individual, often rustic style of dress, and greeted one another with ‘Heil’.

The year before the outbreak of World War I saw the centenary of the Battle of the Nations at Leipzig, in which Prussian, Austrian and German forces had decisively beaten Napoleon. In commemoration, Kaiser Wilhelm II unveiled a monument at the scene of the fighting. The Wandervogel and other leagues of youth seized on the occasion to come together under the banner of the Bündische Jugend. A Festival of Youth was held on the evening of 11 October, when groups of boys and girls, including socialists and students from the nearby universities of Marburg, Göttingen and Jena, converged on a site at the Hohe Meissner, a mountain south of Kassel. The area was steeped in romantic legend; here, according to ancient folklore, lived Frau Holle, the legendary maker of snow. One speaker declared, ‘The Free German Youth is determined to shape its own life, to be responsible to itself and guided by the innate feeling of truth. To defend this inner liberty, they close their ranks.’

With the outbreak of war in August 1914 came the belief that the conflict would sweep away the machinery of capitalist bureaucracy, together with the materialism so many of the Wandervogel despised. Disillusion was not long in coming. In Flanders, the XXVI Reserve Corps of the Fourth Army was sent into battle with orders to take the village of Langemarck, a heavily-defended strongpoint within the British position. The XXVI Reserve Corps, made up from young volunteers, was all but annihilated. To this day the visitor to the salient is faced with a cemetery containing 25,000 soldiers, buried together in a mass grave.

Above the chaos of battle at Langemarck, according to legend, an ardent voice could be heard intoning the future German national anthem, Deutschland Lied, Deutschland über Alles. The voice was taken up by others until there was mass singing amid the thunder of the English guns. While the stretcher bearers and the medics strove to remove the wounded and the dead, the singing could be heard across the battlefield, unceasing even while knots of survivors, clutching their rifles, returned to the action.

Whatever the truth of the legend, Langemarck served as useful propaganda, which the Nazis were quick to exploit when later sacrifices were required by German youth. The heady romanticism and youthful idealism that characterized the Wandervogel was coarsened by the sufferings of war. Within some of the youth groups, only praise for the virtues of peasant life survived intact.

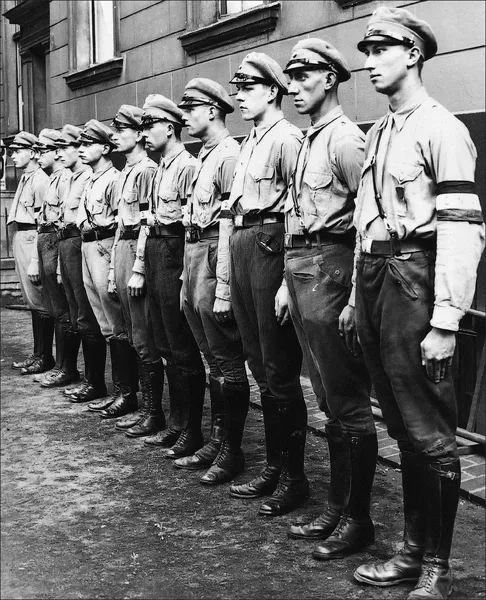

Alongside those who strove to keep the ideals of the Wandervogel alive were such groups as the Bündische Jugend, whose followers looked back to the highlights of German military history, their factions adopting such titles as Bismarck, Tannenberg, Hindenberg or Scharnhorst. One of the most significant indications of the way in which such groups were developing was a widespread adoption of uniforms. These often took the form of shorts and a particular colour of shirt, whether white, blue, brown or grey. Distinctive headgear, notably the beret, was widely favoured and there were individual emblems and banners.

MUNICH PUTSCH

November 1923 saw Hitler, in a disastrous misjudgement, make a bid in Munich to seize power and overthrow the state government of Bavaria. The attempt ended in farce: Hitler was arrested and sentenced to five years’ penal servitude, although he was released under amnesty within the year. During that time, 19-year-old Gustav Adolf Lenk was leader of the Jugendbund, an adjunct of the brown-shirted Sturmabteilung (Storm Troopers), or SA. Lenk was soon facing a rival, however.

Members of the Bismarck Jugend, one of the youth groups which had always been on the political Right and which lost little time in proclaiming its alliance to Adolf Hitler after he became Chancellor in January 1933.

Prescribed uniforms and insignia were slow to evolve in the early days of the Hitler Jugend, as this picture at an HJ rally on 1 May 1933 clearly shows. The distinctive HJ badge was yet to be adopted.

Kurt Gruber was a 20-year-old law student who had formed the Grossdeutsche Jugendbewegung (GDJB, Greater German Youth Movement). In an ensuing power struggle, Gruber emerged as the predominant force, his organization being recognized as the official youth movement of the National Socialist German Workers (Nazi) Party. During the course of the second Reichsparteitag (National Party Rally) at Weimar in July 1926, the GDJB was renamed Hitler Jugend, Bund Deutscher Arbeiterjugend (Hitler Youth, Union of German Worker Youth), inevitably shortened to Hitler Jugend. Gruber was appointed Reichsführer with responsibility for Youth Affairs throughout the whole of Germany and Austria.

Hitler, while careful to praise the endeavours of the Hitler Youth, was at the same time notoriously distrustful of any groups within his National Socialist organization that might pose even the remotest threat. To make sure Gruber’s powers remained strictly limited, Hitler appointed a powerful corrective in Hauptmann Franz Felix Pfeffer von Salomon, a Prussian of Huguenot extraction and already a veteran Nazi. He had served in Westphalia as a member of the Freikorps, the private army of ex-soldiers that was raised at the end of the World War I. More significantly, von Salomon had served as Chief of the SA and, as Hitler intended, the links with the Storm Troopers remained.

The Hitler Jugend was organized on a regional basis. This map shows the various districts in 1938, after the Anschluss (union) with Austria and the absorption of the Sudetenland into the Greater German Reich.

Hitler and Ernst Röhm, head of the Sturm Abteilung (Storm Troopers or SA) which initially controlled the Hitler Jugend. The two organizations frequently made joint appearances at party rallies until the fall of the SA.

The SA’s most formidable presence was Ernst Röhm, the hardline professional soldier who considered his Storm Troopers to be the very essence of the Nazi revolution. By the end of 1931, the ranks of the SA’s brown-shirted bully boys, addicted to intimidation and street violence, had been expanded to 170,000 men. This constituted the main force within the National Socialist Pa...