State-of-the-Art Nanopharmaceutical Drug Delivery Platforms for Antineoplastic Agents

Georgi Ts. Momekov*, 1, 2, Denitsa B. Momekova1, 2, Plamen T. Peykov1, Nikolay G. Lambov1, 2 1Faculty of Pharmacy, Medical University-Sofia, 2 Dunav Str., 1000Sofia, Bulgaria; 2National Centre for Advanced Materials UNION, Sofia, Bulgaria

Abstract

The anticancer agents share the distinction of having the lowest therapeutic indices among clinically utilized drug classes and hence antineoplastic chemotherapy is associated with dose-limiting toxicities. Moreover, many of the cytotoxic agents are characterized with pharmacokinetic problems, e.g., limited stability, fast elimination and low level of tissue penetration, further limiting their usefulness. The advances in our understanding of the tumor biology and microenvironment characteristics and the evolvement of nano-sized systems, suitable as drug-delivery platforms have conditioned immense research interest towards design and elaboration of tumor-targeted nano carriers. Based on the possibilities for ensuring tumor- or organ targeted delivery and triggered or controlled release nanocarriers allow for augmented and sustained anticancer activity of loaded agents, with a concomitant decreased systemic exposure and toxicity. Moreover, nano-carriers could also aid for improvement of the biopharmaceutical, stability and solubility characteristics of encapsulated drugs. The presented review gives a concise outline of the liposomes, polymeric micelles and related polymeric carriers, and molecular hosts as anticancer drug delivery platforms.

Keywords: : Antineoplastic agents, targeted drug delivery, EPR effect, PEG, liposomes, nanoparticles, polymeric micelles, dendrimers, molecular hosts.

* Address correspondence to Georgi Ts. Momekov: Department of Pharmacology, Pharmacotherapy and Toxicology, Faculty of Pharmacy, MU-Sofia, Bulgaria; Tel: +3592 9236 509; Fax: +3592 9879 874;, E-mails: [email protected], [email protected] Introduction

The poor physicochemical and pharmacokinetic properties of the majority of classical anticancer drugs conditions the obvious inability to deliver them at adequate amounts within the malignant formations with concomitant avoidance of the normal non-target organs and tissues [1]. Thus the rapid clearance and the

associated need for repetitive administration of antineoplastic agents, particularly in high dose chemotherapy, in turn lead to significant adverse effects or toxicities on rapidly proliferating or specifically susceptible cellular populations, requiring a dose reduction or even treatment cessation [2-7]. This efficacy vs safety dilemma has been a paramount caveat limiting the clinical success of anticancer chemotherapy [1, 8].

One of the most intriguing strategies to overcome the limitations of classical cytotoxic drugs is their formulation into nanopharmaceutical platforms, i.e., nano-scale carriers, such as liposomes [9-11], polymeric nanoparticles (nanospheres, nanocapsules, polymeric micelles, multi-arm core-shell co-polymers, protein or polysaccharide conjugates) [12-14], and more recently into nano-containers based on host-guest interactions [15-20]. Due to their unique properties the nanopharmaceuticals offer significant advantages over classical parenteral formulations of anticancer drugs and have been well demonstrated to decrease drug binding to non-pharmacological targets, to favorably alter the systemic and intratumoral trafficking of encapsulated agents and to greatly ameliorate the debilitating dose-limiting toxicities, associated with this class of therapeutic agents (Table 1) [21, 22].

Table 1 Rationale for Nanopharmaceutical Delivery of Anticancer Drugs | Advantages Over Free Drug | Nanopharmaceutical Delivery Systems |

| Liposomes | Polymeric Micelles/

Dendrimers/Stars | Molecular

Hosts |

| Passive tumor targeting | • | • | • |

| Active tumor targeting | • | • | • |

| Possibilities for triggered drug release | • | • | |

| Increased bioavailability | • | • | • |

| Protection of encapsulated cargo and increased chemical stability | • | • | • |

| Prolonged half-life | • | • | |

| Sustained drug release | • | • | |

| Modified biodistribution and lower organ toxicity | • | • | |

| Enhanced cytosolic delivery | • | • | |

| Increased solubility of lipophilic drugs | • | • | • |

| Co-delivery of drug combinations | • | • | |

To a great extent this is due to the fact that drugs are encapsulated within nanocontainers with controlled microenvironment, whereby the drug is protected from side interactions with body tissue components, xenobiotic efflux transporters and biotransformation systems. Thus the pharmacokinetics and tissue distribution of a drug encapsulated in a nanoplatform are no more dependent on its intrinsic pharmacokinetic properties, but are governed by the tissue disposition and elimination patterns of the carrier [23, 24]. Moreover, additional benefits of nanoparticulate systems include sustained or trigerrable release kinetics, increased bioavailability at the respective targets sites with concomitant increased efficacy, reduction of the nominal dosage required and amelioration of the severity and incidence of adverse reactions [23-25].

This review is focused on representative examples of nanopharmaceutical platforms with special emphasize on liposomes, globular architecture polymeric nanoparticles (micelles, dendrimers and stars) and macrocyclic molecular hosts.

Passive tumor Targeting by nanopharmaceuticals

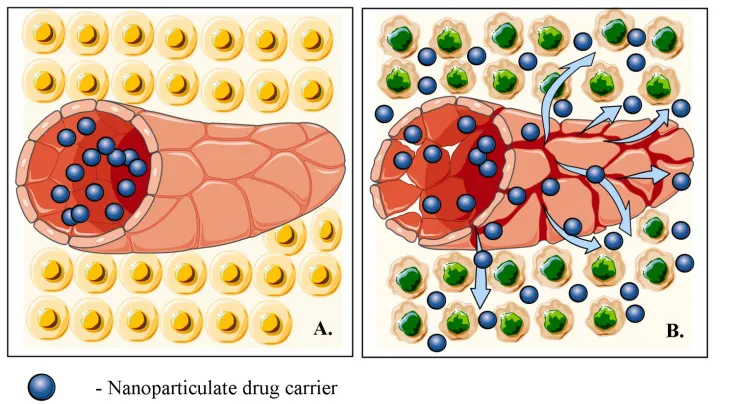

It is well known that the growth of solid malignant tumors is dependent on a process of de novo formation of blood vessels known as angiogenesis [26, 27]. The newly formed vasculature of tumors however is leaky relative to the vessels in normal tissues which makes solid tumors hyperpermeable towards colloid-sized carriers, e.g., liposomes and polymer nanoparticles [10, 28, 29]. This specific compromised barrier function of the vasculature, together with the inadequate lymphatic drainage of tumors conditions the accelerated accumulation of blood-borne nanoparticles, i.e., the ‘enhanced permeability and retention effect’ (EPR effect) (Fig. 1). EPR has been the central paradigm that has fuelled the development of antineoplastic nanopharmaceuticals during the last three decades [26, 28-32].

One of the hallmark challenges associated with nanocarriers is that these have to circulate long enough in order to attain enough accumulation at tumor lesions via the EPR [24, 33, 34]. Due to the colloidal size of nanocarriers these are recognized and phagocytized by the cells of the mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS) (previously designated as reticuloendothelial system or RES) which leads to disappointingly short circulation half-lives [10, 35-37]. The most important approach towards bypassing MPS sequestration has been the incorporation of PEG residues on the surface of polymer particles or liposomes [33, 38-41]. PEGylation creates a hydrophilic repulsive barrier around nanocarriers which increases their colloidal stability, hinders interactions with serum components and opsonins, and eventually prevents recognition by the MPS cells [33]. This imparts MPS-avoidance or “stealth” properties to the delivery device, increasing its systemic circulation time significantly [21, 33, 40, 42]. Moreover, PEGylation of macromolecular carriers has been well documented to favorably decrease their immunogenicity [43], although some of the adverse effects associated with stealth liposomes, have been attributed to immune responses (see below).

Fig. (1)) Schematic representation of the EPR effects based on the discrepanci...