- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This volume contains a series of essays aimed at illuminating the theory, history, and roots of imperialism, which extend the analysis developed in Magdoff's The Age of Imperialism.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Imperialism by Harry Magdoff in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Volkswirtschaftslehre & Volkswirtschaft. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

4

Imperialism Without Colonies

The sudden upsurge during the late nineteenth century in the aggressive pursuit of colonies by almost all the great powers is, without doubt, a primary distinguishing trait of the “new imperialism.” It is surely the dramatic hallmark of this historic process, and yet it is by no means the essence of the new imperialism. In fact, the customary identification of imperialism with colonialism is an obstacle to the proper study of the subject, since colonialism existed before the modern form of imperialism and the latter has outlived colonialism.

While colonialism itself has an ancient history, the colonialism of the last five centuries is closely associated with the birth and maturation of the capitalist socioeconomic system. The pursuit and acquisition of colonies (including political and economic domination, short of colonial ownership) was a significant attribute of the commercial revolution which contributed to the disintegration of feudalism and the foundation of capitalism. The precapitalist regional trade patterns around the globe were not destroyed by the inexorable forces of the market. Instead, it was superior military power that laid the basis for transforming these traditional trade patterns into a world market centered on the needs and interests of Western Europe. The leap ahead in naval power-based on advances in artillery and in sailing vessels able to carry the artillery—created the bludgeoning force used to annex colonies, open trading ports, enforce new trading relations, and develop mines and plantations. Based on mastery of seapower, this colonialism was mainly confined to coastal areas, except for the Americas where the sparse population had a primitive technology and was highly susceptible to European infectious diseases.1 Until the nineteenth century, economic relations with these colonies were, from the European standpoint, import-oriented, largely characterized by the desire of the metropolitan countries to obtain the esoteric goods and riches that could be found only in the colonies. For most of those years, in fact, the conquering Europeans had little to offer in exchange for the spices and tropical agricultural products they craved, as well as the precious metals from the Americas.

The metropolitan-colonial relation changed under the impact of the Industrial Revolution and the development of the steam railway. With these, the center of interest shifted from imports to exports, resulting in the ruination of native industry, the penetration of large land areas, a new phase in international banking, and increasing opportunity for the export of capital. Still further changes were introduced with the development of large-scale industry based on new metallurgy, the industrial application of organic chemistry, new sources of power, and new means of communication and of ocean transport.

In the light of geographic and historical disparities among colonies and the different purposes they have served at different times, the conclusion can hardly be avoided that attempts such as have been made by some historians and economists to fit all colonialism into a single model are bound to be unsatisfactory. There is, to be sure, a common factor in the various colonial experiences; namely, the exploitation of the colonies for the benefit of the metropolitan centers.2 Moreover, there is unity in the fact that the considerable changes in the colonial and semicolonial world that did occur were primarily in response to the changing needs of an expanding and technically advancing capitalism. Still, if we want to understand the economics and politics of the colonial world at some point in time, we have to recognize and distinguish the differences associated with the periods of mercantile capitalism, competitive industrial capitalism, and monopoly capitalism, just as we have to distinguish these stages of development in the metropolitan centers themselves if we want to understand the process of capital development.

The identification of imperialism with colonialism obfuscates not only historical variation in colonial-metropolitan relations, but makes it more difficult to evaluate the latest transformation of the capitalist world system, the imperialism of the period of monopoly capitalism. This obfuscation can often be traced to the practice of creating rigid, static, and ahistoric conceptual models to cope with complex, dynamic phenomena. I propose to examine some of the more common misconceptions on which models of this kind are often based in the belief that it will help clarify the theme of imperialism without colonies. Two such misconceptions are particularly common, both of which relate to the vital role played by the export of capital: those based on arguments concerning the export of surplus capital and the falling rate of profit in the advanced capitalist countries.

1. The Pressure of Surplus Capital

A distinguishing feature of the new imperialism associated with the period of monopoly capitalism (that is, when the giant corporation is in the ascendancy and there is a high degree of economic concentration) is a sharp rise in the export of capital. The tie between the export of capital and imperialist expansion is the obvious need on the part of investors of capital for a safe and friendly environment.

But why the upsurge in the migration of capital during the last quarter of the nineteenth century and its continuation to this day? A frequently-met explanation is that the advanced capitalist nations began to be burdened by a superabundance of capital that could not find profitable investment opportunities at home and therefore sought foreign outlets. While a strong case can be made for the proposition that the growth of monopoly leads to increasing investment difficulties, it does not follow that the export of capital was stimulated primarily by the pressure of a surplus of capital.3

The key to answering the question lies, in my opinion, in understanding and viewing capitalism as a world system. The existence of strong nation states and the importance of nationalism tend to obscure the concept of a global capitalist system. Yet the nationalism of capitalist societies is the alter ego of the system’s internationalism. Successful capitalist classes need the power of nation states not only to develop inner markets and to build adequate infrastructures but also, and equally important, to secure and protect opportunities for foreign commerce and investment in a world of rival nation states. Each capitalist nation wants protection for itself, preferential trade channels, and freedom to operate internationally. Protectionism, a strong military posture, and the drive for external markets are all part of the same package.

The desire and need to operate on a world scale is built into the economics of capitalism. Competitive pressures, technical advances, and recurring imbalances between productive capacity and effective demand create continuous pressures for the expansion of markets. The risks and uncertainties of business, interrelated with the unlimited acquisitive drive for wealth, activate the entrepreneur to accumulate ever greater assets and, in the process, to scour every corner of the earth for new opportunities. What stand in the way, in addition to technical limits of transportation and communication, are the recalcitrance of natives and the rivalry of other capitalist nation states.

Viewed in this way, export of capital, like foreign trade, is a normal function of capitalist enterprise. Moreover, the expansion of capital export is closely associated with the geographic expansion of capitalism. Back in the earliest days of mercantile capitalism, capital began to reach out beyond its original borders to finance plantations and mines in the Americas and Asia. With this came the growth of overseas banking to finance trade with Europe as well as to help lubricate foreign investment operations. Even though domestic investment opportunities may have lagged in some places and at some times, the primary drive behind the export of capital was not the pressure of surplus capital but the utilization of capital where profitable opportunities existed, constrained, of course, by the technology of the time, the economic and political conditions in the other countries, and the resources of the home country. For example, since military power was needed to force an entry into many of these profit-making opportunities, shortages of manpower and economic resources that could readily be devoted to such purposes also limited investment opportunities.

As mentioned above, a reversal in trade relations occurs under the impact of the industrial revolution and the upsurge of mass-produced manufactures. Capitalist enterprise desperately searches out export markets, while it is the overseas areas which suffer from a shortage of goods to offer in exchange. As a result, many of the countries which buy from industrialized countries fall into debt, since their imports tend to exceed their exports. Under such conditions opportunities and the need for loan capital from the metropolitan centers expand. Capital exports thus become an important prop to the export of goods. As is well known, the real upsurge in demand for British export capital came with the development of the railway. It was not only British industry that supplied the iron rails and railroad equipment over great stretches of the globe, but also British loan and equity capital that made the financing of these exports possible. In addition, the financial institutions which evolved in the long history of international trade and capital export acquired vested interests in the pursuit of foreign business. Following their own growth imperatives, they sought new opportunities for the use of capital overseas, while energetically collecting and stimulating domestic capital for such investments.

The important point is that capital export has a long history. It is a product of (1) the worldwide operations of the advanced capitalist nations, and (2) the institutions and economic structure that evolved in the ripening of capitalism as a world system. It is not the product of surplus capital as such. This does not mean that there is never a “surplus capital” problem (fed at times by the return flow of interest and profits from abroad), nor that at times capital will not move under the pressure of such surpluses. Once sophisticated international money markets exist, various uses will be made of them. Short-term funds, for instance, will move across borders in response to temporary tightness or ease of money in the several markets. Money will be loaned for more general political and economic purposes, for one country to gain influence and preferential treatment in another. But the main underpinning of the international financial markets is the international network of trade and investment that was generated by the advanced industrial nations in pursuit of their need to operate in world markets. Thus, while surplus domestic capital may at times be a contributing factor to capital movements abroad, the more relevant explanation, in our opinion, is to be found in the interrelations between the domestic economic situation of the advanced capitalist nations and that of their overseas markets.4

Why then the sudden upsurge of capital exports associated with modern imperialism? The answer, in my opinion, is consistent with the above analysis as well as with the nature of this later stage of capitalism. First, the onset of the new imperialism is marked by the arrival of several industrial states able to challenge Britain’s hegemony over international trade and finance. These other nations expand their capital exports for the same purposes—increased foreign trade and preferential markets. Thus, instead of Britain being the dominant exporter of capital among very few others, a new crop of exporters comes to the fore, with the result that the total flow of capital exports greatly expands. Second, associated with the intensified rivalry of advanced industrial nations is the growth of protective tariff walls: one means of jumping these tariff walls is foreign investment. Third, the new stage of capitalism is based on industries requiring vast new supplies of raw materials, such as oil and ferrous and nonferrous metal ores. This requires not only large sums of capital for exploration and development of foreign sources, but also loan capital to enable foreign countries to construct the needed complementary transportation and public utility facilities. Fourth, the maturation of joint stock companies, the stock market, and other financial institutions provides the means for mobilizing capital more efficiently for use abroad as well as at home. Finally, the development of giant corporations hastens the growth of monopoly. The ability and desire of these corporations to control markets provides another major incentive for the expansion of capital abroad.

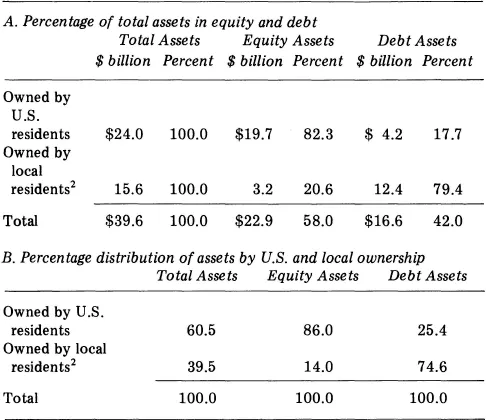

The facts on U.S. investment abroad in the present era are quite revealing on the issue of “surplus” capital; they can help us to answer the historical questions as well. One would expect that if a major, if not the major, reason for the export of U.S. capital today were the pressure of a superabundance of domestic capital, then as much capital as could be profitably used abroad would be drawn from the United States. But that is not the case. We have the data on the capital structure of U.S. direct investments abroad in the year 1957. (This is the latest year for which such data are available. Another census of foreign investments was taken in 1966, but the results have not yet been published.) What we find is that 60 percent of the direct investment assets of U.S.-based corporations are owned by U.S. residents and 40 percent by non-U.S. residents, mainly local residents, but including overseas European and Canadian capital invested in Latin America, etc. (see Table I.B).

Now there is an interesting twist to these data. If we separate equity and debt assets, we discover that U.S. residents own 86 percent of the equity and only 25 percent of the debt. What this reflects is the practice employed by U.S. firms to assure control oyer their foreign assets and to capture most of the “perpetual” flow of profits. As for the debt capital (long- and short-term), which in time will be repaid out of the profits of the enterprise, it is just as well to give the native rich a break. The supposedly pressing “surplus” funds of the home country are tapped very little for the debt capital needs of foreign enterprise.

Table I

U.S. Direct-Investment Enterprise in Other Countries in 19571: Assets Owned by U.S. and Local Residents

U.S. Direct-Investment Enterprise in Other Countries in 19571: Assets Owned by U.S. and Local Residents

(Details may not add up to totals because of rounding off of decimals.)

1. Finance and insurance investments are excluded.

2. More accurately, non-U.S. residents. The owners are primarily residents of the areas in which U.S. enterprise is located, though there was probably a flow of funds from Europe and Canada to U.S.-owned enterprise in other areas.

1. Finance and insurance investments are excluded.

2. More accurately, non-U.S. residents. The owners are primarily residents of the areas in which U.S. enterprise is located, though there was probably a flow of funds from Europe and Canada to U.S.-owned enterprise in other areas.

Source: Calculated from U.S. Business Investments in Foreign Countries (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Commerce, 1960), Table 20.

But we should also be aware that the 60-40 share of the capital assets, mentioned above, exaggerates the capital funds supplied from the United States. Here is how a businessman’s publication, Business Abroad, describes the overseas investment practices of U.S. corporations:

In calculating the value of capital investment, General Motors, for example, figures the intangibles such as trademarks, patents, and know-how equivalent to twice the actual invested capital. Some corporations calculate know-how, blueprints, and so on as one third of capital investment, and then supply one third in equity by providing machinery and equipment.5

Hence, a good share of the 60 percent of the assets owned by U.S. firms does not represent cash investment but a valuation of their knowledge, trademarks, etc., and their own machinery valued at prices set by the home office.6

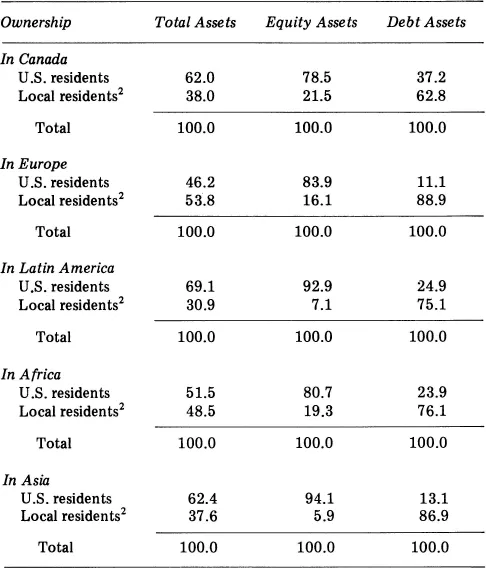

One may ask whether this phenomenon of using local capital is a feature predominantly of investment practices in wealthier foreign countries. The answer is no. It is true that the share supplied by local capital is larger in European countries (54 percent) and lower in Latin American countries (31 percent), but the practice of obtaining debt capital locally is characteristic of all regions in which U.S. capital is invested (see Table II).

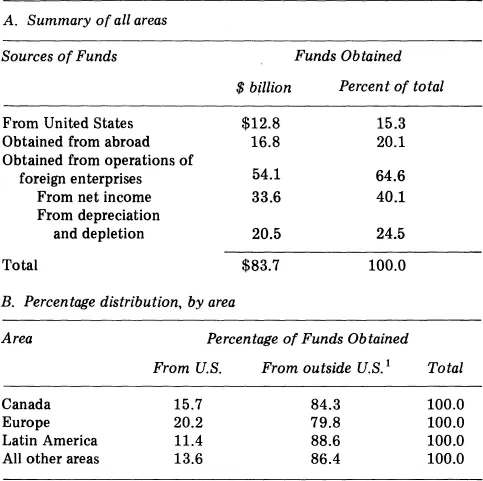

The facts on the flow of funds to finance U.S. direct investments abroad are even more striking. We have data on the source of funds used to finance these enterprises for the period 1957 to 1965. While this information is for a limited period, other available evidence indicates that there is no reason to consider this period as atypical.7

These data reveal that during the period in question some $84 billion were used to finance the expansion and operations of direct foreign investments. Of this total, only a little more than 15 percent came from the United States. The remaining 85 percent was raised outside the United States: 20 percent from locally raised funds and 65 percent from the cash generated by the foreign enterprise operations themselves (see Table III.A).

Table II

Percentage Distribution of Assets of U.S. Direct-Investment Enterprises in Other Countries, by Ownership and Area (in 1957)1

Percentage Distribution of Assets of U.S. Direct-Investment Enterprises in Other Countries, by Ownership and Area (in 1957)1

Notes and source: As Table I.

Table III

Sources of Funds of U.S. Direct-Investment Enterprises in Other Countries: 1957-1965

Sources of Funds of U.S. Direct-Investment Enterprises in Other Countries: 1957-1965

1. Includes funds raised abroad from non-U.S. residents and from operations of foreign enterprises.

Source: 1957 data—same as Table 1; 1958-1965 data from Survey of Current Business, September 1961; September 1962; November 1965; January 1967.

Here again the pattern is similar for rich countries and poor countries. If anything, the U.S. capi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- A Technical Note

- History

- Theory and the Third World

- Reply to Critics