![]()

CHAPTER ONE

One-with-Nature Theory

“Nature can never be completely described, for such a description of nature would have to duplicate nature. No name can fully express what it represents. It is nature itself, and not any part abstracted from nature, which is the ultimate source of all that happens, all that comes and goes, begins and ends, is and is not. But to describe nature as the ‘ultimate source of all’ is still only a description, and such a description is not nature itself Yet since, in order to speak of it, we must use words, we shall have to describe it as ‘the ultimate source of all.’”

Lao Tze

translated by Archie Bahm

“Once Chuang Chou dreamt he was a butterfly, a butterfly flitting and fluttering around, happy with himself and doing as he pleased. He didn’t know he was Chuang Chou. Suddenly he woke up and there he was, solid and unmistakable, Chuang Chou. But he didn’t know if he was Chuang Chou who had dreamt he was a butterfly, or a butterfly dreaming he was Chuang Chou.”

Chuang Chou Tze

Nature and the Self

Coaxed by curiosity, a trait we consider an intrinsic part of human nature, we make great discoveries and succeed in little, important ways in our daily lives. But most great discoveries do not come easily, especially when dealing with fundamental questions about the self and nature. We continue to debate ancient philosophical questions about the relationship of humans to nature. And we probe these questions with science. Who are we? What is nature? What is our place in nature? Chuang Chou, more than 2,000 years ago, described not just human imagination, but a fleeting perception of the self as integral to nature.

Philosophers, scientists, literary men and women, and other thinkers have provided diverse answers to these important questions. But answers to these questions must lie within the mind and heart, where scientific and philosophical modes merge. Scientists make hypotheses to describe physical systems, as Sir Isaac Newton did when describing the motion of a physical force. Consider his hypothesis that for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction.

This hypothesis allowed Newton to develop classical mechanics, a discipline still used by scientists today to physically describe nature. The word action is usually not defined in terms of reactions at all, but it is a definition of action that scientists can use. You, however, might not find it useful in everyday life.

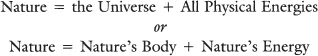

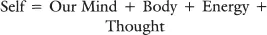

If we are to understand, in a scientific way, the relationship between nature and the self, we must also begin with a hypothesis. For me, as an engineering physicist, nature is a physical system composed of matter and energy. We can call the matter constituting nature the “universe,” or the “body of nature.” And we can call the physical energies in nature “nature’s energy.” With these simple terms, we can describe nature in this equation.

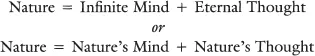

We can use a similar equation to describe nature philosophically. We can begin with a hypothesis based on the assumption that nature is composed of an infinite mind (nature’s mind) and an eternal thought (nature’s thought). So, we can describe nature in these terms.

Some people have described God in similar terms; one dictionary defines God as “infinite mind,” “eternal,” “that which is without beginning and end.” Eternal thought, then, is thought which has no beginning and no end. For simplicity, we can refer to these attributes as nature’s mind and nature’s thought.

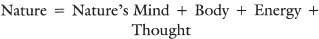

If we combine these scientific and philosophical approaches to describing nature into one, here is the resulting definition of nature.

The word nature in this equation represents a physical–philosophical system composed of four essential elements. Since we are part of this physical–philosophical system, our being has the same composition as nature. Therefore, these same four elements may describe ourselves.

Note the distinction between thought and the mind. This is because thoughts may be considered things existing within the mind. The mind, in other words, acts as the thoughts’ body just as the brain acts as the mind’s body. Also, remember that the word ch’i means “inner energy,” or energy inside the body.

These diagrams illustrate the four elements of each system.

The Tao of Becoming One with Nature

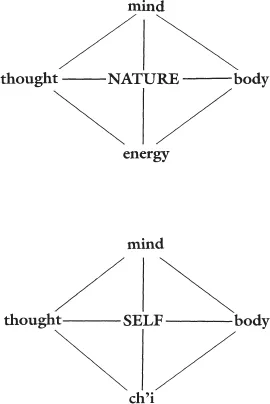

Let’s use the four basic elements of nature and the self to describe the four conditions of being one with nature.

I am one with nature . . .

when my mind is with nature’s mind

when my body is with nature’s body

when my ch’i is with nature’s energy

when my thought is with nature’s thought

The four elements of being one with nature can be understood in the diagram on p. 19 in which the self, one’s own existence, is surrounded by nature, expressed as universal, infinite, and eternal.

Bringing our state of being in line with that of nature is necessary if we are to make use of nature to heal ourselves. We can begin the process by asking ourselves these four basic questions.

How can my mind be with nature’s mind?

How can my body be with nature’s body?

How can my ch’i be with nature’s energy?

How can my thought be with nature’s thought?

We can answer these questions in a simple way by recognizing that since nature created us, nature can also help us become one with itself. In accord with nature, the one-with-nature method described in this book can facilitate this process. Consider the words of Lao Tze.

“Things which act naturally do not need to be told how to act. The wind and rain begin without being ordered and quit without being commanded. This is the way with all natural beginnings and endings. If nature does not have to instruct the wind and rain, how much less should humans try to direct them? Whoever acts naturally is nature itself acting.”

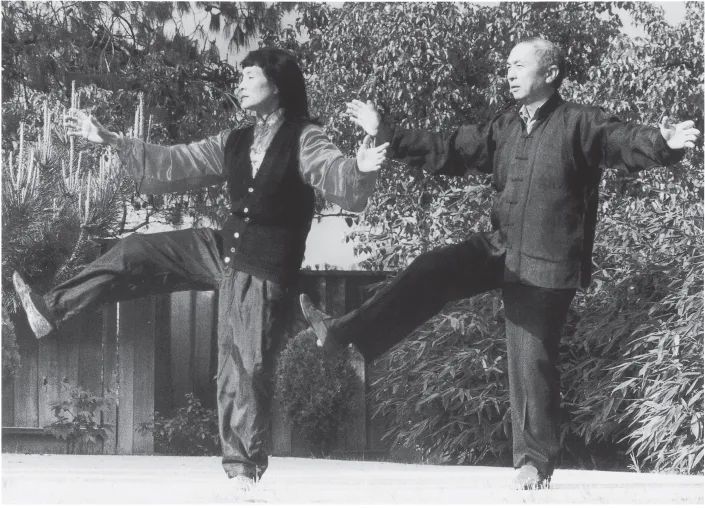

Tai Chi Masters Dr. Martin Lee and Emily Lee (shown above) received a grant from the National Institute of Aging to conduct a study from 1999 to 2002 on the benefits of tai chi for seniors under the Wellness Intervention for Self-Enrichment (WISE) project in association with the Stanford Center for Research on Disease Prevention.

The participants, most of whom were in their mid-70s, were volunteers over age 65. Before the study began, all seniors were in good general health, able to walk without assistance, and classed as “sedentary” because they exercised less than 60 minutes a week.

In this study, the Lees gave the seniors free tai chi instruction.

Study participants practiced tai chi twice a week for 6 months, then once a week for 6 months. The sedentary seniors found many of the same benefits as younger tai chi students. Most seniors were able to incorporate tai chi principles and practice into their daily lives almost immediately. In fact, these seniors, the Lees found, have achieved the same benefits as more active senior students enrolled in their regular Tai Chi for Total Fitness classes.

![]()

CHAPTER TWO

Becoming One with Nature

Drawing on more than 20 years’ experience of teaching tai chi to thousands of students, I devised a simple, practical way of teaching my students how to become one with nature. I often tell beginning students:

“I am a scientist. As a scientist I work with physical systems. But I am also a tai chi master, and as a tai chi master, I also understand the body as a mental and physical system. Let’s see what we have inside this mental and physical system: We all have a mind and a body, and inside the mind, we have thoughts. Thoughts are like the coffee inside a cup. The cup, then, is the mind and the coffee represents the thoughts. Similarly, inside the body, we have energy. Because this energy is inside us, we may think of it as inner energy”

We are all familiar with the concept of energy. Sunlight outside is, for example, full of energy. Scientists learn about energy by looking outward at nature, and many neglect attending to the energy that exists inside the body. Since nature does not distinguish between outside and inside, energy that exists outside the body must also exist inside. So, the ch’i inside us is the same as the energy to be found outside the body.

In the diagram of the self, four parts—mind, body, ch’i, and thought—are connected and form a single system. Well-being can be defined in terms of the relationships among these four parts. If all these relationships are intact, you are healthy, but if any relationship is not intact, you may get sick. What disrupts the vital, natural relationship of mind, body, ch’i, and thou...