![]()

CHAPTER 1

Innovation and National Competitiveness

Introduction

Since the industrial revolution in the late 1700s, innovation has been the driving force behind economic growth and advancement in the military might of nations; namely, USA, UK, and a number of European countries. The emergence of science in the 1600s created the environment for the development of technology to power the world ahead for the next three centuries. Yet, one problem persists; very few nations have truly mastered the art to manage innovation, which is the manner to institutionalize the process to advance science and technology, to accelerate economic growth and empower the government.

The process of innovation begins with ‘research’ and moves to ‘development’. This is called ‘Research & Development’ (R&D). Research discovers and explains nature, sometimes even inventing a new way to manipulate things. Using new technology, development creates new products or services to generate revenue. R&D develops, from science, technology and invents new products.

Take, for example, the discovery of DNA. As scientists, Watson and Crick discovered the geometric form of the gene, the double-stranded helix model, through scientific investigation. That inspired Boyer and Cohen (also as scientists) to discover a way to manipulate and alter genes through the technique of recombinant DNA. This paved the way for Boyer and Swanson to start the first biotech company, Genentech, to produce therapeutic proteins by manipulating the genes of e-Coli bacteria. From this (1) science of DNA, (2) technology of recombinant DNA, and (3) commercialization of therapeutic proteins, the new biotechnology industry was born. This has been the pattern of innovation: (1) scientific discoveries, (2) technological inventions, and (3) commercial ventures to produce new products using new technology. Innovation is science combined with invention plus commercialization of new ways to use nature.

However, we face another problem. As most new scientific researches are normally carried out in universities, while most new commercialization efforts are undertaken in industry, conflicts of interest do exist between the two parties. We have the pursuit of knowledge and new discoveries by university scientists on the one hand, and the need to generate revenue and profits for shareholders and CEOs on the other. How can they cooperate so as to simultaneously advance science and develop technology?

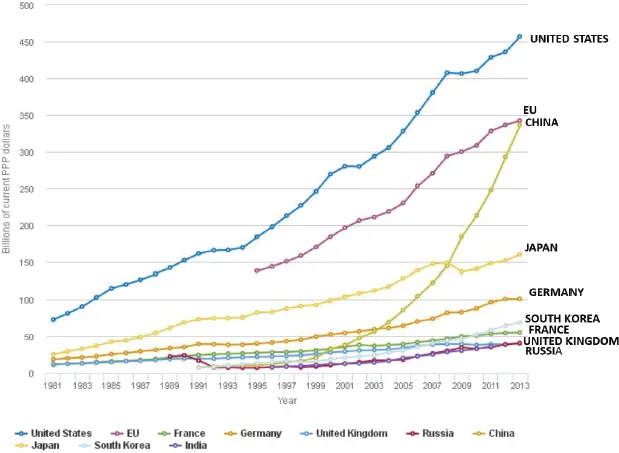

Here is an important fact about R&D: nations which do the most R&D have the largest economies in the world. National Gross Domestic Product (GDP) correlates with national R&D, as demonstrated in Figure 1.1, which shows the levels of global research & development (R&D) in areas with high GDP figures. One can see that in North America ($492 billion), Europe ($367 billion), and East and Southeast Asia ($614 billion), these countries have significant R&D expenditure, in the range of hundreds of billions of U.S. dollars.

The next most interesting thing about R&D is that it is performed on a national scale. Plotting the size of a nation’s R&D against its GDP shows vividly that unless a nation invests in R&D, its economy cannot effectively compete on a global scale (see Figure 1.2).

After the Second World War, the United States has become the largest investor in R&D (science & technology) and has continued doing so into the 21st century, with an R&D expenditure of over $450 billion dollars. The European Union nations also have some of the highest GDPs in the world, and an R&D expenditure of $340 billion. Nevertheless, 40 years of an ‘open-up’ policy and economic reforms instigated by Deng in the 70s, have propelled China to become the world’s second largest economy (by nominal GDP) and the world’s largest economy (by purchasing power parity) according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF). China’s state companies also invested in R&D, so much so that by 2013, China’s R&D expenditures equaled those of the EU.

Figure 1.1.Global R&D expenditures, by region in 2013.

Source: NSF Science Indicators 2016.

Figure 1.2.Expenditures on R&D 1981–2013.

Source: NSF Science Indicators 2016. https://www.nsf.gov/statistics/2016/nsb20161/#/

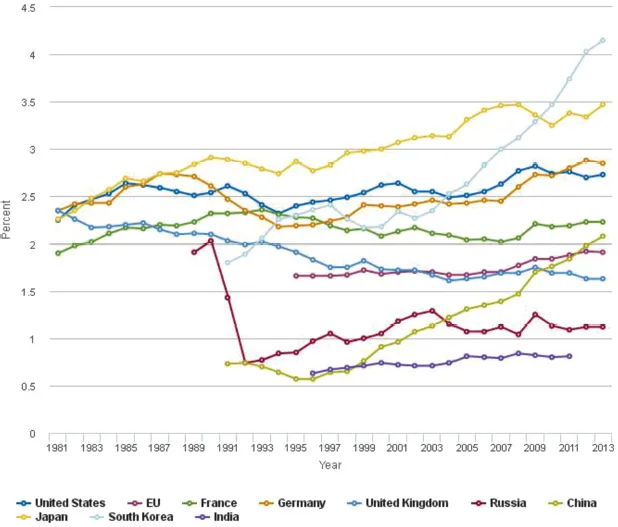

Expenditure on R&D is a significant cost to a nation. For a nation to be globally competitive, its R&D expenditure needs to rest in the range of 2–4% of the nation’s GDP (R&D/GDP) (see Figure 1.3).

Over the last two decades, the United States’ expenditure ratio (R&D/GDP) has been around 2.5%, while Germany’s ratio climbed to 3.5%, South Korea’s to over 4%, and Japan’s and China’s to 2%. On the other hand, the United Kingdom’s ratio fell to 1.6%. India’s ratio is around 0.8%, and Russia’s ratio is just above 1%.

Figure 1.3.R&D expenditures as % of GDP 1981–2013.

Source: NSF Science Indicators 2016.

What is most striking is that the Asian countries, such as Japan and South Korea, are committing a high percentage of their GDP to R&D, since they know that science and technology are vital factors in improving their nation’s global competitiveness. China, the third Asian country, is rapidly increasing its investment in science and technology. The US, Germany, France, and the United Kingdom recently are holding steady in their investment in R&D (as a percentage of their GDP). Russia and India are not seriously committed to the costs of becoming a high-tech economy.

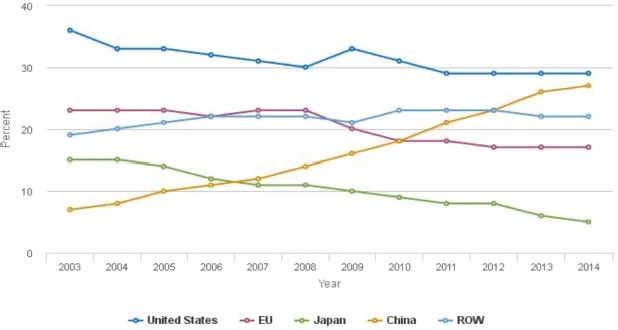

Since R&D results in the commercialization of products, one can also see a correlation between the levels of R&D expenditure and the output of high-tech products by the different countries of the world (see Figure 1.4).

With its large R&D expenditures, the United States leads the world in the manufacturing of high-tech products at 29% output. The EU, with its large R&D expenditure, produces about 23% of high-tech manufactured products. And with the rapidly growing R&D expenditure in China, the Chinese share of hightech manufactured products has grown to about 27%. (A historical footnote: the rapid growth of high-tech manufacturing in China was due to United States’ industry outsourcing much of its manufacturing to China from the late 1980s, in order to reduce the cost in manufacturing, as technologies in manufacturing processes were being automated and controlled with computational technology.)

Figure 1.4.Percentage output of global high-tech industries 2003–2014.

Source: NSF Science Indicators 2016.

In summary, innovation has played and continues to play a significant role in the world’s industrialization and a nation’s global competitiveness. Innovation may be expensive, but it is an important investment as R&D contributes to economic growth.

Science and Technology Policy Definitions

Let us next briefly review some of the key terms in R&D, such as nature, science, technology, commercialization, products — these are all central concepts to policies about innovation and economic growth. In the scientific and engineering communities, the term ‘nature’ is commonly used to refer to essential qualities of things that can be observed in all the universe. (1) ‘nature’ is the totality of the essential qualities of the observable phenomena of the universe.

The derivation of the term ‘science’ comes from the Latin term ‘scientia’, meaning ‘knowledge’. However, the modern concept of scientific research has come to indicate a specific approach toward knowledge, which results in the discovery and explanations of nature. (2) ‘science’ is the discovery and explanation of nature. For science and technology (S&T) policies, the important institutional aspect is that science is mostly performed in universities (and not in industries or in government research labs).

The technical side of the idea of technological innovation — invention — derives from the idea of technology. The historical derivation of the term ‘technical’ comes from the Greek word ‘technikos’, meaning ‘of art, skillful, [and] practical’. The suffix of the word ‘ology’ refers to the ‘knowledge of’ or ‘systematic treatment of’ ‘technikos’. Thus, the term ‘technology’ literally translates to ‘knowledge of the skillful and practical’. This meaning of ‘technology’ is a common definition of the term — but too vague for expressing precisely the interactions between science, technology and economy. The ‘knowledge of the skillful and practical’ is knowledge of how to ‘manipulate’ the natural world. Technology is useful knowledge, i.e. knowledge of a functional capability. In all technologies, there is always some form of nature manipulation. Accordingly, we will use a more precise definition: (3) ‘Technology’ is the knowledge of the manipulation of nature for human purposes. For S&T policies, the important institutional aspect is that technology is mostly developed in industry (and not in universities or in government research labs).

Previously, not all technology in the world was invented upon a base of scientific knowledge. Before the emergence of science in the 1600s, previous technologies such as fire, stone weapons, agriculture, boats, writing, bronze, iron and guns were all invented before science. As a result, people with technical knowledge who understood how to apply, put technologies to work and made inventions. To improve technologies, one must understand how they functioned. What science does for technology is explain why technologies work. After the conception of science, all important technologies in the world have been invented upon knowledge based on science. (4) ‘Scientific technology’ is a technology invented upon a scientific base of knowledge, which explains why the technology works. For S&T policies, the important institutional aspect is that scientific technology is most rapidly advanced through university-industry research cooperation.

Technologies are implemented in products and services by designing and embedding the technical knowledge into the operation of the product/service. Engineers do the designing; their designs enable businesses to use nature (through technology) to add value to products. (5) ‘Engineering’ is the design of economic artifacts embodying technology. For S&T policies, the important institutional aspect is that the engineering design of products is mostly performed in industry.

Products and services provide utility to the customers who purchase them. Through products/services, the concept of ‘utility’ provides the functionality of a technology to a human for a purpose. Thus, economic utility is created by a product or service sold in a market that provides a functional value for its customer. Take for example xerography products, which provide the function of copying (duplicating) the contents of printed papers to the customer, at a much quicker rate than copying by hand.

In a society, its technology connects nature to its economy; hence, we will define the term ‘economy’ to indicate this. The common usage of the term ‘economy’ indicates the administration, management or operation of the resource(s) and productivity of a household, business, nation, or society. But we will use the term ‘economy’ in the following way: (6) ‘Economy’ is the social process of the human use of nature as utility. For S&T policies, the important institutional aspect is that economic growth is mostly achieved by industry (and not by universities or the government).

Business organizations provide the social forms for economic activities. The leadership in an economic organization is provided by the management staff of the business. (7) ‘Management’ is the form of leadership in economic processes. For S&T policies, the important institutional aspect of industrial management is that it serves both private and public good in a national economy.

In modern economies, the direct connection between technology and economy are in the products, processes and services that embody change in the technologies, which a business uses in an ...