- 172 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Acrylamide in Food

About this book

Acrylamide, a chemical described as 'extremely hazardous' and 'probably carcinogenic to humans', was discovered in food in 2002. Its presence in a range of popular foods has become one of the most difficult issues facing not only the food industry but

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Acrylamide in Food by Nigel G Halford, Tanya Y Curtis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Chemistry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction: Toxicology of Acrylamide and its Formation in Food

1.1. What is Acrylamide?

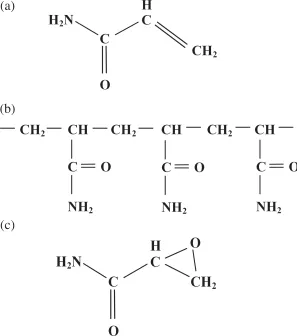

Acrylamide (Figure 1.1), also known as acrylic amide and prop-2-enamide, is a white, odourless, crystalline, water-soluble solid, with the chemical formula C3H5NO and relative molecular mass of 71.08. In its monomeric form, it is regarded as a hazardous chemical: in the USA, for example, it is classified as an extremely hazardous substance under the Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act (42 U.S.C. 11002). Acrylamide is a potent neurotoxin (nerve toxin), affects male reproduction, causes birth defects and is carcinogenic (cancer-causing) in laboratory animals (Section 1.2). It is readily absorbed through the skin, by inhalation and from the gastrointestinal tract.

Acrylamide forms a polymer, polyacrylamide (Figure 1.1), and in this form is not considered significantly toxic and does not penetrate the skin. Polyacrylamide has a variety of industrial uses as a flocculant (used to separate solid matter from liquid), binding agent and thickener in wastewater and sewage treatment, the production of paper, plastic products, grout, cement, pesticides, food packaging, dyes and cosmetics, the treatment of soil to prevent erosion, ore processing and sugar manufacturing. It is also a familiar material in biochemistry and molecular biology laboratories, where it is used to make thin gels used for the separation of nucleic acids or proteins by electrophoresis (polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, or PAGE). The USA polyacrylamide market was worth $576 million in 2015.

Figure 1.1. (a) Diagram showing the structure of acrylamide (C3H5NO). (b) Diagram showing the structure of acrylamide chains in polyacrylamide. Cross-links form between the nitrogen atoms on different chains to produce an insoluble matrix. (c) Diagram showing the structure of glycidamide (C3H5NO2), a metabolite of acrylamide.

Polyacrylamide may contain a small amount of soluble, monomeric acrylamide as an impurity, and since polyacrylamide is used in water treatment there is a risk of the monomer contaminating the water, and acrylamide is therefore a recognised potential water pollutant. The World Health Organization has set a guideline value for the presence of acrylamide in water of 0.5 µg per litre, or 0.5 parts per billion (ppb), with the proviso that exposure should be reduced to as low a level as technically achievable. In a sense, the guideline value is arbitrary because it would be extremely difficult to detect the presence of acrylamide at that concentration: essentially, if acrylamide is detectable then the water is considered to be polluted and an urgent investigation of the source of the acrylamide should follow. Fortunately, acrylamide is biodegraded by micro-organisms, so does not persist in soil or lakes.

1.2. Metabolism and Toxicology

The use of acrylamide in industrial processes means that there is a risk of occupational exposure and exposure to acrylamide as a pollutant. Acrylamide is also present in tobacco smoke. Once absorbed, it spreads rapidly around the body, can cross the placenta and is also present in small amounts in breast milk. Acrylamide is metabolised to produce glycidamide (C3H5NO2) (Figure 1.1), also known as oxirane-2-carboxamide or glycidic acid amide. Different animal species convert acrylamide to glycidamide with varying efficiency, and there may be differences between individuals within species, including humans, as well. This is important because glycidamide may be responsible for the genotoxic and carcinogenic effects attributed to acrylamide. Glycidamide forms adducts with DNA both in vitro (in a testtube) and in vivo in human and animal tissues; indeed, glycidamide–DNA adducts can be used as markers for acrylamide exposure. Acrylamide itself will also form adducts with DNA in vitro, but these adducts have never been found in animal or human tissues.

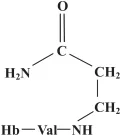

Both acrylamide and glycidamide also react with glutathione, an important antioxidant. This represents the primary detoxification and excretion route, the glutathione adducts that are formed being converted in the liver to organic acids called mercapturic acids, which are then excreted in urine. The presence of mercapturic acids of acrylamide and glycidamide can be measured in urine and are another marker for acrylamide exposure. A third type of marker for exposure arises from reactions of acrylamide and glycidamide with proteins, notably haemoglobin in the blood. Indeed, the detection of acrylamide–haemoglobin adducts in blood tests is the favoured method for obtaining quantitative measurements of acrylamide exposure. The adduct N-(2-carbamoylethyl)valine (CEV) (Figure 1.2) forms with the valine residues at the N-termini of the globin chains in haemoglobin, with the ratio of adducts to globin chains providing a measure of acrylamide exposure. These adducts are detected using mass spectrometry (MS) after removal from the N-terminal end of the protein by a modification of the Edman degradation method. Edman degradation is used to determine the sequence of amino acids at the N-terminal end of a protein, the amino acid residues being sequentially removed and analysed. The modified method (the N-alkyl Edman method) is used to remove the CEV adduct.

Figure 1.2. Structure of the adduct CEV, which forms through the reaction of acrylamide with the N-terminal valine residue of a globin chain of haemoglobin (Hb).

Toxicological studies with acrylamide have been conducted in a range of animal species, including rats, mice, guinea pigs, monkeys, cats and dogs. The results of these studies were analysed by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA)’s Scientific Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain (CONTAM), and summarised in the CONTAM Panel’s ‘Scientific Opinion on Acrylamide in Food’ report of 2015 (published in the EFSA Journal, Volume 15, and available for download at https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2015.4104). The CONTAM Panel concluded that high doses of acrylamide caused loss of body weight and effects on the nervous system, including paralysis in hind-limbs, reduction in rotarod performance (a test that evaluates balance, grip strength and coordination) and changes in peripheral nerves and nervous system structures. In mice, there were also effects on the testes, sperm count, stomach, spleen, preputial gland (a specialised sex gland), lungs and ovaries. In rats, there were effects on skeletal muscle, testes, the bladder, preputial glands, spleen, bone marrow, ovaries, retina, liver, lymph nodes and pituitary gland.

Both acrylamide and glycidamide have been shown to be genotoxic, i.e. to damage DNA, in many studies. In mammalian cell cultures, acrylamide has a weak mutagenic activity but is a powerful clastogen; in other words, it causes chromosome breakages, leading to deletions or rearrangements in the DNA. Glycidamide, on the other hand, is both a strong mutagen, causing changes in the sequence of nucleotides in the DNA where it forms adducts, and a strong clastogen. Acrylamide has also been shown to be clearly genotoxic in animal studies, primarily but not exclusively after metabolism to glycidamide. The carcinogenic effect of acrylamide in rodents is also not disputed, with tumours induced in multiple tissues in both male and female mice and rats. Toxicological studies on rodents and other animals, of course, use high doses of the chemical being tested so that statistically significant effects can be demonstrated. This is no different for acrylamide, and the doses of acrylamide used are typically measured in mg per kg body weight.

Early data on the effects of acrylamide in humans came from studies on the effects of occupational exposure. In 1993, for example, Emma Bergmark, then at the University of Washington, Seattle, and colleagues studied workers in a factory in China who were involved in the manufacture of acrylamide. Exposure was determined by measuring acrylamide– haemoglobin adducts, and elevated levels of adducts were found in the blood of the exposed workers. Several of the workers showed signs of peripheral neuropathy (damage to peripheral nerves, affecting sensation or movement) and the effects correlated with the levels of acrylamide adducts. This enabled the team to estimate a no observed adverse effect level (NOAEL) of 2000 pmol adducts per gram of globin, and a lowest observed adverse effect level (LOAEL) of 6000 pmol adducts per gram of globin. The CONTAM Panel report of 2015 noted that other studies had also shown effects on the central nervous system.

The international authority on the carcinogenicity of chemicals to humans is the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), the specialised cancer agency of the World Health Organization. The IARC publishes its findings and opinions in a series of monographs, classifying chemicals on the basis of studies in humans and experimental animals, as well as mechanistic data, assessing the strength of the evidence that any carcinogenic effect is due to a particular mechanism and whether that mechanism is likely to operate in humans. An overall evaluation is reached, considering all the evidence, and the chemical is assigned to one of the following groups: Group 1, carcinogenic to humans; Group 2A, probably carcinogenic to humans; Group 2B, possibly carcinogenic to humans; Group 3, not classifiable as to its carcinogenicity to humans; Group 4, probably not carcinogenic to humans.

The IARC’s overall evaluation for acrylamide is that it is probably carcinogenic to humans (Group 2A). This evaluation is based on the strong evidence of carcinogenicity in experimental animals but the limited evidence available of carcinogenic effects in humans.

1.3. The Discovery of Acrylamide in Cooked Food

Emma Bergmark continued her studies on acrylamide after moving to the University of Stockholm. In 1997, she reported the results of a study of laboratory personnel who were regularly using PAGE. In our experience, laboratory workers generally take great care in handling dangerous chemicals, and even by the 1990s were able to purchase ready-made gel mixes rather than having to weigh out acrylamide powder themselves. Nevertheless, adducts of acrylamide and haemoglobin were detectable in blood samples collected from the laboratory personnel, with those using PAGE showing significantly increased levels of adducts compared with non-smoking controls. The adducts detected in the smokers in the study correlated with the number of cigarettes smoked per day. Bergmark also noted high levels of adducts in the non-smoking controls, i.e. non-smokers who did not use PAGE, and remarked that ‘the origin of this background is not known’.

Other studies on occupational exposure to acrylamide also reported a high level of background adducts in control groups, and in 2000 a team led by Margareta Törnqvist, also at the University of Stockholm, reported the results of a study investigating whether cooked food could be a source of acrylamide. Rats that were fed fried animal standard feed for 1 or 2 months showed much higher levels of haemoglobin-acrylamide adducts than control rats fed unfried feed. The team showed that acrylamide formed during the heating of the feed, and that the amount of acrylamide that formed was consistent with the measured levels of adducts in the rats. Notably, the levels of adducts observed in the animals fed the fried feed were similar to the ‘background’ level reported in non-smoking people with no occupational exposure to acrylamide. The team concluded that cooked food was probably a major source of acrylamide exposure.

The title of the report on this study, which was published by the journal Chemical Research in Toxicology, Volume 13, pages 517–522, was Acrylamide: A Cooking Carcinogen? Nevertheless, it seems to have passed under the radar until another paper from Törnqvist’s team was published in 2002. That paper, which was published in the Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, Volume 50, pages 4998–5006, and called ‘Analysis of Acrylamide, a Carcinogen Formed in Heated Foodstuffs’, reported on an investigation into whether acrylamide could be formed in heated human foods. The team found that small amounts of acrylamide (5–50 µg per kg, or ppb) formed in heated, protein-rich foods (hamburgers), and much higher levels (150–4000 ppb) in carbohydrate-rich foods, such as potato and beetroot. They also found high levels of acrylamide in some commercial potato products and crispbread. It is not clear why these products were chosen for study, except that they are popular in Sweden, but the fact that they were chosen led, through no fault of the authors, to the incorrect assumption by many that the problem of acrylamide in food was largely one affecting potato products and crispbread, whereas it was soon found that other cereal products and coffee were also important contributors to dietary acrylamide (Section 1.5).

The study found that acrylamide was not detectable in uncooked food. Acrylamide can therefore be classified as a processing contaminant, which we define as a substance that is produced in a food when it is cooked or processed, is not present or is present at much lower concentrations in the raw, unprocessed food, and is undesirable either because it has an adverse effect on product quality or because it is potentially harmful. The study also found that acrylamide did not form to detectable levels in any of the boiled foods that were analysed, and acrylamide continues to be associated predominantly with fried, baked, roasted or toasted foods (Section 1.5).

It was the publication of this paper that ...

Table of contents

- Cover page

- Title page

- Copyright

- Preface

- About the Authors

- Contents

- Chapter 1 Introduction: Toxicology of Acrylamide and its Formation in Food

- Chapter 2 The Response of International Food Safety Authorities

- Chapter 3 Measures Taken by the Food Industry to Reduce Acrylamide Levels

- Chapter 4 Agronomic and Genetic Approaches to Reducing the Acrylamide-forming Potential of Wheat and Rye

- Chapter 5 Agronomic and Genetic Approaches to Reducing the Acrylamide-forming Potential of Potato

- Chapter 6 Conclusions

- Index