- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Elemental carbon materials take numerous forms including graphite, carbon fiber, carbon nanotube, graphene, carbon black, activated carbon, fullerene and diamond. These forms differ greatly in the structure, properties, fabrication method, and applicat

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Carbon Materials by Deborah D L Chung in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Materials Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

Materials ScienceChapter 1

Introduction to carbon materials

1.1Introduction

Carbon is an element with atomic number 6. It is in Group IV of the Periodic Table of the Elements. The allotropes of carbon are graphite, diamond and fullerene (Fig. 1.1). The densities of graphite and diamond are 2.26 and 3.52 g/cm3, respectively.

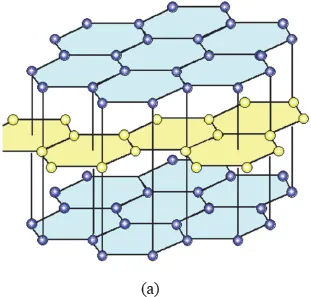

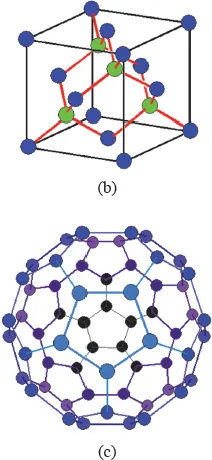

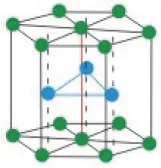

Fig. 1.1 The three allotropes of carbon. (a) Graphite, with the two colors inidcating the A and B layers in the AB stacking sequence. (https://www.tf.uni-kiel.de/matwis/amat/iss/kap_4/advanced/t4_2_1.html#_dum_3, public domain) (b) Diamond. (https://www.tf.uni-kiel.de/matwis/amat/iss/kap_4/illustr/i4_2_1.html, public domain) (c) Fullerene. Pentagons and hexagons are present. (http://www.gcsescience.com/a38-buckminsterfullerene.htm, public domain).

1.1.1Graphite

Graphite has the carbon atoms sp2 hybridized, so that each carbon has three covalent bonds (σ bonds) directed to three other carbons in the same plane (Fig. 1.1(a)). The fourth valence electron that is not engaged in the sp2 hybridization is delocalized through π-π interaction, resulting in in-plane metallic bonding. Thus, within the layer, the bonding is a mixture of covalent bonding and metallic bonding. In contrast, the adjacent layers are weakly bonded through van der Waals forces. Therefore, graphite is highly anisotropic, with mechanical, electrical and thermal properties that are very different between the in-plane and out-of-plane directions. In the in-plane direction, the elastic modulus is high and the coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE) is low, due to the strong in-plane covalent bonding. The electrical conductivity and thermal conductivity are high in the in-plane direction, due to the in-plane metallic bonding. In the out-of-plane direction, the modulus, electrical conductivity and thermal conductivity are very low, due to the weak van der Waals forces between the layers.

The carbon layers in graphite are stacked in the AB sequence, so that adjacent layers are shifted with respect to one another. It should be noted that the graphite structure is different from the hexagonal close-packed (HCP) structure that is exhibited by many metals. The HCP also exhibits the AB stacking sequence, but the structure of each layer is different and the shift between the layers is also different (Fig. 1.2).

Fig. 1.2 The hexagonal close-packed crystal structure. (http://nptel.ac.in/courses/113104005/lecture2/2_5.htm, public domain).

1.1.2Diamond

Diamond has the carbon atoms sp3 hybridized, so that each carbon atom has four covalent bonds (σ bonds) directed tetrahedrally to four other carbon atoms (Fig. 1.1(b)). Because all the valence electrons are engaged in the covalent bonds, there are no free electrons. As a result, diamond is an electrical insulator. On the other hand, because of the phonons (lattice vibrational waves) associated with the lightweight carbon atoms, phonon transport is significant, resulting is very high thermal conductivity in diamond. The combination of low electrical conductivity and high thermal conductivity makes diamond quite unique. This combination is attractive for applications such as microelectronic cooling. Due to the covalent network in the crystal structure, diamond is very high in the elastic modulus.

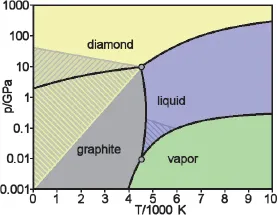

Graphite is thermodynamically stable at ordinary temperatures and pressures, whereas diamond is not. Although diamond is not thermodynamically stable at ordinary temperatures and pressures, it exists as a metastable phase at ordinary temperatures and pressures. Upon heating above room temperature, diamond tends to change to graphite, because the thermal energy would allow the carbon atoms in diamond to move and the movement would cause the conversion of the diamond (a metastable phase) to graphite (the stable phase). On the other hand, the application of high pressure changes graphite to diamond, as indicated by the phase diagram (Fig. 1.3). This is an expensive but feasible method of making diamond.

Fig. 1.3 Calculated phase diagram of carbon, showing the equilibrium phases for various combinations of pressure (vertical axis) and temperature (horizontal axis). (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Carbon_basic_phase_diagram.png, public domain).

At pressures ranging from 0.01 to 10 GPa and a temperature around 4500 K, graphite melts and becomes carbon liquid. At lower pressures ranging from 0.001 to 0.01 GPa and a temperature ranging from 4000 to 4500 K, graphite sublimes and becomes carbon vapor. Because of the very high melting and sublimation temperatures, carbon liquid and carbon vapor have not been studied much.

1.1.3Fullerene

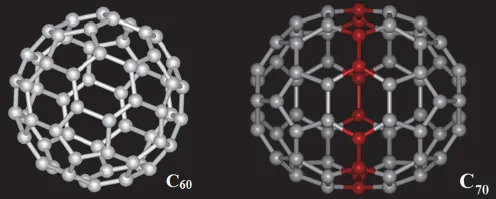

Fullerene is the C60 molecule, which consists of 60 carbon atoms, with no other element (Fig. 1.1(c)). The molecule has the shape of a ball, with diameter about 0.7 nm. Each carbon atom has three bonds that are directed to three other carbon atoms. There is a carbon atom at each corner of the 20 hexagons and 12 pentagons that make up the surface of the ball. The term fullerene was named after the American architect Buckminster Fuller, who designed a large geodesic dome that resembled the molecular structure of C60. These balls are known as bucky balls. The addition of carbon atoms to the equator of the C60 ball gives oblong molecules with formulae C70, C76, C84, etc. (Fig. 1.4). The fullerenes are used as catalysts, lubricants and carriers for delivering drugs into the body.

Fig. 1.4 The structures of the C60 and C70 molecules in comparison. The red balls in C70 indicate the extra 10 carbon atoms present beyond the 60 carbon atoms in C60. (http://electric-carbon-blog.tumblr.com/post/50452158262/on-the-track-of-the-nanotubes-in-nature, public domain).

1.2The graphite family

The graphite family refers to carbon materials that are akin to graphite in the sp2 hybridization of the carbon atoms and the presence of carbon layers in the structure. There are numerous members of this family, as described in this section.

1.2.1Graphite and turbostratic carbon

The graphite family includes graphite (Fig.1.1(a)) (Chapter 2) and turbostratic carbon (Chapter 2), which is noncrystalline carbon that consists of carbon layers that are not well ordered with respect to one another. For example, the carbon layers in turbostratic carbon are not exactly parallel and do not exhibit the AB stacking sequence. In addition, the carbon layer stacks in turbostratic carbon are limited in both in-plane and out-of-plane dimensions. Graphite is the thermodynamically stable form. Upon heating at a sufficiently high temperatures that the carbon atoms can move in the solid state, turbostratic carbon, which is metastable, spontaneously changes to graphite. This change in phase is known as crystallization, also known as graphitization.

1.2.2Carbon fibers and nanofibers

Turbostratic carbon is the main phase in carbon fibers (Chapter 6), carbon nanofibers (Chapter 7) and carbon black (Chapter 4), though these carbon materials can be graphitized to a degree so that crystallites exist as well. Carbon fibers are widely used for lightweight structures, due to their availability in a continuous form and their combination of low density, high strength and high modulus. The high strength and high modulus occur along the fiber axis, due to the preferred orientation of the carbon layers in this direction. In contrast, carbon nanofibers are not continuous, in spite of their high aspect ratio and the feasibility of forming yarns from the discontinuous nanofibers. Furthermore, the small diameter of the nanofibers compared to the fibers causes the fiber-matrix interface area to be large for the nanofiber composites, thus accentuating the problem associated with the mechanically weak link at the fiber-matrix interface. Due to this weak link, the mechanical properties of a nanofiber composite tends to be inferior to that of the corresponding fiber composite.

1.2.3Carbon nanotubes

The graphite family also includes carbon nanotubes (Chapter 7) without the hemispherical cap at either end of the nanotube. The cap belongs to the fullerene family. In other words, the nanotube with the cap is a hybrid of graphite (the trunk of the nanotube) and fullerene (the cap). The nanotubes tend to be smaller in diameter and hence larger in aspect ratio than the nanofibers. As for the nanofibers, the nanotubes are not continuous and suffer from the weak link at the nanotube-matrix interface.

1.2.4Intercalated graphite

The graphite family also includes intercalated graphite (Chapter 2), which is a layered compound (known as an intercalation compound) with foreign species (known as the intercalate) typically in the form of monolayers between the carbon layers. The intercalate layers and carbon layers are stacked so as to form a superlattice along the c-axis. The number of carbon layers between two nearest intercalate layers is known as the stage of the compound. In the ionic form of intercalation compound, there is charge transfer between the carbon and the intercalate, with the intercalate serving as either an electron acceptor or an electron donor. In case of the intercalate being an acceptor (e.g., bromine), the graphite becomes p-type, i.e., a hole metal. In case of the intercalate being a donor (e.g., lithium), the graphite becomes n-type, i.e., an electron metal. The inter...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Series Editor

- Title

- Copyright

- Front

- Preface

- Contents

- 1. Introduction to carbon materials

- 2. Graphite

- 3. Graphene

- 4. Carbon black

- 5. Activated carbon

- 6. Carbon fibers

- 7. Carbon nanofibers and nanotubes

- Index