Oxygen Production and Reduction in Artificial and Natural Systems

- 436 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Oxygen Production and Reduction in Artificial and Natural Systems

About this book

This book is the outcome of a Bioenergetics workshop held at Nanyang Technological University (NTU), Singapore in April 2018 to honour Professor Bertil Andersson for his outstanding contributions to scientific research and administration, particularly his very successful 11 years a NTU as Provost (2007–2011) and President (2011–2018). The main focus of the book is on the mechanisms of photosynthetic oxygen production by water splitting and the reverse respiratory reaction of oxygen reduction to water. Also discussed is how these reactions can be used for the development of artificial photosynthesis for the generation of sustainable solar fuel. The various chapters are written by international experts including Nobel Laureates Rudolph Marcus and John Walker. They provide the very latest knowledge of how the flow of energy in biology is driven by sunlight and efficiently utilized to power life. This book is suitable for students and researchers who are interested in molecular details of energy flow on our planet and also concerned about sustainability of humankind.

Contents:

- How Biology Solved Its Energy Problem and Implications for the Future of Humankind (James Barber)

- Theory of Rate Constants of Substeps in Single Molecule Experiments on F 1 -ATPase (Sándor Volkán-Kacsó and Rudolph A Marcus)

- Redox- and Light-Driven Hydration Dynamics in Biological Energy Transduction (Ville R I Kaila)

- Reflections on Redox States in Enzymes (Per E M Siegbahn)

- The Role of Singlet Oxygen in Photoinhibition of Photosystem II (Imre Vass)

- Modular Assembly of ATP Synthase (John E Walker, Jiuya He and Joe Carroll)

- Cytochrome c Oxidase — Remaining Questions About the Catalytic Mechanism (Mårten Wikström and Vivek Sharma)

- Cytochrome c Oxidase: Oxygen Consumption, Energy Conservation and Control (Peter R Rich)

- Mimicking the Oxygen-Evolving Center in Photosystem II (Changhui Chen, Yang Chen and Chunxi Zhang)

- Protein Environment that Facilitates Proton Transfer and Electron Transfer in Photosystem II (Hiroshi Ishikita)

- Key Molecular Ru Complexes that have Fostered the Development and Understanding of Water Oxidation Catalysis (Carolina Gimbert Suriñach and Antoni Llobet)

- Material Design for Artificial Photosynthesis using Photoelectrodes for Hydrogen Production (Wilman Septina, James Barber and Lydia Helena Wong)

- Synthesis, Electronic Structure, and Spectroscopy of Multinuclear Mn Complexes Relevant to the Oxygen Evolving Complex of Photosystem II (Heui Beom Lee, Paul H Oyala and Theodor Agapie)

- Progress Towards Unraveling the Water-Oxidation Mechanism of Photosystem II (Hao-Li Huang, Ipsita Ghosh, Gourab Banerjee and Gary W Brudvig)

- Structure and Mechanism of Ni- and Fe-containing Carbon Monoxide Dehydrogenases (Holger Dobbek)

- Selective Replacement of the Damaged D1 Reaction Center Subunit During the Repair of the Oxygen-Evolving Photosystem II Complex (Shengxi Shao, Jianfeng Yu and Peter J Nixon)

- DFT Investigations on the Reaction Mechanisms in Photosynthetic Oxygen Evolution (Yu Guo)

- Local Cycle of Photosynthesis and Quasi-Aerobic Respiration Facilitated by Manganese Oxides — A Hypothesis on the Evolution of Phototrophy (Holger Dau, Dennis J Nürnberg and Robert Burnap)

- A Perspective on a Paradigm Shift in Plant Photosynthesis: Designing a Novel Type of Photosynthesis in Sorghum by Combining C 3 and C 4 Metabolism (Christer Jansson, Todd Mockler, John P Vogel, Henrique DePaoli, Samuel P Hazen, Venkat Srinivasan, Asaph Cousins, Peggy Lemaux, Jeff Dahlberg and Tom Brutnell)

Readership: Graduate students, researchers and specialists interested in various aspects of respiratory and photosynthetic electron trasport chains, and the development of artificial photosynthesis for the generation of sustainable solar fuel. Photosynthesis;Artificial Photosynthesis;Electron Transport Chains;Oxygen Production;Oxygen Reduction;Water Splitting;Solar Fuels;Light Harvesting00

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Chapter 1

How Biology Solved Its Energy Problem and Implications for the Future of Humankind

[email protected]

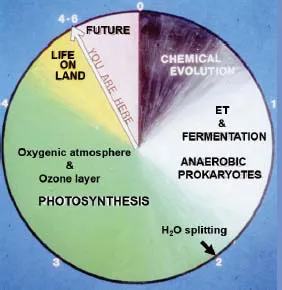

1.Evolution of Bioenergetics

1.1.Under anaerobic conditions

1.2.Under aerobic conditions

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword by James Barber FRS

- Preface

- Chapter 1 How Biology Solved Its Energy Problem and Implications for the Future of Humankind

- Chapter 2 Theory of Rate Constants of Substeps in Single Molecule Experiments on F1-ATPase

- Chapter 3 Redox- and Light-Driven Hydration Dynamics in Biological Energy Transduction

- Chapter 4 Reflections on Redox States in Enzymes

- Chapter 5 The Role of Singlet Oxygen in Photoinhibition of Photosystem II

- Chapter 6 Modular Assembly of ATP Synthase

- Chapter 7 Cytochrome c Oxidase — Remaining Questions About the Catalytic Mechanism

- Chapter 8 Cytochrome c Oxidase: Oxygen Consumption, Energy Conservation and Control

- Chapter 9 Mimicking the Oxygen-Evolving Center in Photosystem II

- Chapter 10 Protein Environment that Facilitates Proton Transfer and Electron Transfer in Photosystem II

- Chapter 11 Key Molecular Ru Complexes that have Fostered the Development and Understanding of Water Oxidation Catalysis

- Chapter 12 Material Design for Artificial Photosynthesis using Photoelectrodes for Hydrogen Production

- Chapter 13 Synthesis, Electronic Structure, and Spectroscopy of Multinuclear Mn Complexes Relevant to the Oxygen Evolving Complex of Photosystem II

- Chapter 14 Progress Towards Unraveling the Water-Oxidation Mechanism of Photosystem II

- Chapter 15 Structure and Mechanism of Ni- and Fe-containing Carbon Monoxide Dehydrogenases

- Chapter 16 Selective Replacement of the Damaged D1 Reaction Center Subunit During the Repair of the Oxygen-Evolving Photosystem II Complex

- Chapter 17 DFT Investigations on the Reaction Mechanisms in Photosynthetic Oxygen Evolution

- Chapter 18 Local Cycle of Photosynthesis and Quasi-Aerobic Respiration Facilitated by Manganese Oxides — A Hypothesis on the Evolution of Phototrophy

- Chapter 19 A Perspective on a Paradigm Shift in Plant Photosynthesis: Designing a Novel Type of Photosynthesis in Sorghum by Combining C3 and C4 Metabolism

- Index