![]()

Chapter 1

The Role of Parents in Supporting Mathematics Learning

In order to properly learn mathematics, one needs to appreciate it for its power and beauty and not fear it because of the unjust reputation it continues to receive in our culture. Many believe that this is the responsibility of the teacher, namely, to motivate children to like the subject and to make the instruction as interesting as possible. However, the truth of the matter is that the role of the parents is absolutely critical in this endeavor. Parents shape their children’s beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors in many areas of their lives, mathematics included. In this chapter we will discuss the role the parent can play to support their child’s learning of mathematics.

Why Should I Care About Liking Math?

If you are reading this book, you might have a child who struggles with math or possibly dislikes it. Maybe your child comes home every day and complains about any math related issues he or she is responsible for, such as multiplication, word problems, algebra, geometry, or trigonometry. The words, “When will I ever use this in real life?” are likely part of your child’s complaints as he or she sits down to complete his or her “dreaded” math homework. Maybe your child doesn’t do his or her homework at all. Why does it even matter? And since you are reading this book, maybe you agree. Math is unfortunately portrayed as frustrating and useless, so why are we torturing our children by making them learn something they believe they will “never use?” We need to dispel these notions and make every effort to model positive attitudes towards mathematics continuously. Let us consider a common scenario that might play itself out in many homes.

Johnny is an 11-year-old boy. Every day when he comes home from school, homework is a battle. His parents attempt to sit down with him and help him with his homework, but he doesn’t want to do it, particularly the math homework. Arguments about homework completion are a daily occurrence.

“This is stupid!” He shouts. His mother responds to him, “I know you don’t like math. I don’t like it either! But you have to just be quiet and do it!”

“But why? If you don’t even like it, why do I have to do it?” he inquires.

“Because math is important,” his mother reminds him.

But does Johnny’s mother really believe that? And does Johnny believe her? It is possible that the answers are “No.”

Many children (and adults) struggle with math and may dislike it. It is easy to see why math has gotten a bad reputation. Johnny’s parents tell him all about what school was like for them and what their favorite subjects were when they were his age. Oftentimes, they tell him that they “didn’t like” math or that it was difficult for them. When Johnny comes home with barely passing grades in math, they sigh with relief and say, “at least he passed.”

Yet, Johnny’s parents do not do this for other school subjects. In fact, they might read stories with him every night before he goes to bed and take him to the history and science museums on the weekends. When he receives just-passing grades in English, history, and science, his parents ask, “What happened? This is unacceptable!”

So, do we really blame Johnny for not liking math and thinking that it is useless? Maybe not. At times, it seems useless. Unless you are a construction worker, engineer, chef, doctor, nurse, architect, clothing designer or mathematician, when did you last calculate a circumference, employ a logarithm, or find a derivative? What about finding the length of a hypotenuse of a right triangle or solving for x?

Between managing finances, calculating tips, crafting, cooking meals and decorating the house, we are willing to bet you use math more than you realize. Because the truth is, math is important, and the skills of problem solving and critical thinking that are clearly demonstrated in math can help children grow into successful adults and will prove immeasurably useful in forming their general reasoning ability, not to mention the many career options that will open to them in this technological era. By keeping a few concepts in mind, Johnny’s parents can help him develop a mindset that appreciates math and problem solving and also show him that math does not have to be scary and frustrating. It can be beautiful, understandable, and fun.

This chapter will discuss how parents can use their language, expectations, and behavioral principles to help children succeed in math and even enjoy it. Chapter 2 will explore how anxiety around math, in diverse degrees, is relatively common and will survey some of the reasons behind this phenomenon as well as some approaches and suggestions for addressing and minimizing such anxiety. Chapter 3 will assist parents in learning basic math concepts as they are used in today’s elementary grades, while chapters 4, 5, and 6, respectively, will provide you with some practical applications, some amusing aspects of math, and some entertaining stories that you can share with your child to show that it can come “alive.” We hope this will give you a more positive picture of this important subject matter. For now, you’ll have to take our word for it that math is useful and can be fun, because your child’s achievement and confidence in math is important and will contribute to his or her academic and professional success.

The Powerful Role That Parents Play

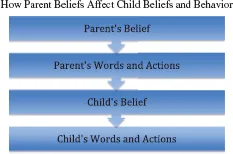

As a parent, you most likely realize the powerful role that you play in your child’s life. Children look to their parents for almost everything: shelter, food, clothing, advice, and believe it or not, attitudes. First, you must be aware of the powerful connection between your beliefs and your children’s beliefs. You might not realize how your beliefs affect your language and behaviors. Your children are constantly listening to you and watching you while formulating their own beliefs, very often based on your beliefs.

Let’s look at some examples of how children learn about their parents’ beliefs without them being explicitly taught. Have you ever noticed a parent who always seemed to need to get his or her way in a situation? The parent might cause a scene or put up a fuss if things do not go exactly as he or she wishes. For example, the parent might bark orders at waiters and waitresses and complain that the service in a restaurant is not good enough. Now imagine how his or her children may behave. It is likely that the children will adopt a similar mindset and may not treat others with respect. The children might get in trouble in school or throw tantrums when they are told, “no” to a request. They might hold the belief that their needs are more important than others — which may be the message being unintentionally, but implicitly, taught by the parent. On the other hand, this can work in a positive direction as well. You might know a parent who is extremely generous, caring, and giving. This parent might be someone who always brings gifts or food when visiting and might be the first one to volunteer to help someone with whatever is needed. It is likely that this parent’s children learn how to share and go out of their way to make sure other children feel included and have fun. Refer to the following flowchart that depicts how parents’ beliefs often affect their children’s beliefs and behavior.

Some of you may not be entirely convinced. It seems at times that children act in a way opposite to our beliefs. For example, how often do your children use poor manners when you want them to be polite, or stay out late when you want them to come home at a reasonable hour? However, children are surprisingly perceptive to the belief systems of their parents and will generally act in similar ways. Of course, as children mature, they develop their own beliefs, attitudes, and ways of interacting with others. They also realize that they are independent humans, who can behave in ways that do not need to align with the beliefs of others. They test limits and push boundaries.

However, parents are some of the most influential figures in their children’s lives, and they fall into a trap when they expect their children to act in a way that is different from the way they act. Think of the parent who always needs to get his or her way. Does that parent want his or her child to act the same way? Most likely, the parent does not. Behavioral change can be a complex process that includes a variety of interventions; however, to start the process, parents must reflect on their own behavior and attitudes.

What Does a Child’s Attitude Have to do With Math?

You may be asking yourself how belief systems and attitudes are related to being good at math. As we pointed out previously, children develop belief systems and attitudes similar to that of their parents. If you don’t like math, chances are, your child will not like math either. While it is possible that genetics may play a role in one’s dislike for math, as a parent, your beliefs and attitudes regarding math also greatly affect your child’s beliefs and attitudes.

When parents have negative opinions about mathematics, those opinions are transmitted to their children through the parents’ words and behaviors. For some reason, it is socially acceptable to brag about one’s dislike for math, yet rarely, if ever, do people boast about how much they despised English or history. Because of this social norm, parents often speak openly, and in front of their children, about how much they disliked math! This sends a message to children: math isn’t fun; and most people don’t like it, so you shouldn’t have to like it, either.

To illustrate this point, imagine the following conversation between a mother and her elementary-school-aged child:

Sally: Mom, I need help with my homework. Can you come help me?

Mom: Sure, sweetheart. What do you have tonight?

Sally: Spelling, math, and geography.

Mom: Okay, let’s do the spelling and geography together. When your father gets home, he can help you with the math.

Sally: Why can’t you help me with the math as well?

Mom: Oh, Daddy’s just much better at it than I am. I don’t really remember all that stuff. It’s been a long time since I learned it.

This conversation seems innocuous. After all, there is nothing wrong with admitting that you don’t remember something. However, in this example, Sally is getting the message that math is not important enough for her mother to remember, and Mom obviously does not use it very much. It is highlighted by the fact that Mom is willing to help Sally with her other subjects. It’s entirely possible that Mom does not remember all of the state capitals or the countries in Europe; however, she is willing to help Sally with her geography homework anyway, because it does not seem as intimidating. In the future, Sally might brush off math as unimportant or useless when that couldn’t be further from the truth. Sally might also perceive that her mother’s opinion about her math work is rather low and unessential. This can reduce her motivation to learn or appreciate the subject — something we hope to change in this book.

Another message we inadvertently send to children is how difficult math can seem. Parents frequently mention their inability to be successful in math “when I was in school.” Children who hear that their parents “gave up with math” and were not successful at learning the subject or do not recognize the importance of being successful in math may internalize this and decide that they do not need to put in any effort to be successful in math as it is wasted time.

Now, imagine this situation: a child comes home with two test papers — one in mathematics and one in English — each of which is marked with a 70% grade. Imagine what a child thinks, when a parent responds with extreme displeasure that the child got only a 70% grade in English. The parent reproaches the children about their lack of competence in English and how shameful it is to get such a low grade. On the other hand, the parent shows relief that the child passed the math test — albeit with a rather low grade, but nonetheless, passed. Imagine what the child is guided to believe when the parent says, “I am so pleased that you passed your math test, since I couldn’t do better myself.” Now compare the levels of expectation that the parent has transmitted to the child: you must improve your English competence, while I am satisfied with your competence in math. Hence, the child may react by focusing on the English instruction and neglecting the math instruction.

These kinds of conversations occur frequently and have more of an effect than you may realize. Instead of promoting a growth mindset to learning mathematics or learning in general, these conversations have the reverse effect. Remember, parents fall into a trap when they want their children to like math and succeed in it, but speak about how much they disliked math and how poorly they did in the subject regularly.

Below is a list of common phrases that parents sometimes say to their children along with how a child might interpret a seemingly innocuous phrase.

| What Parents Say | What Children Interpret |

| “I hated math” | Hating math is normal |

| “I’m no good at math” | My parents aren’t good at math, so I don’t have to be good at it, either. |

| “I don’t remember how to do this” | Math is useless. My parents don’t ever use it. |

| “Ask your father/mother” | My parent doesn’t like math, so I don’t have to like it, either. I can get someone else to do it for me. |

| “At least you passed” | It isn’t important to be good at math. The bare minimum is enough. |

These phrases discourage children from being open to learning and en...