![]()

1

Dielectric Amorphous-Oxide Electrolytes

M. Helena Braga* and John B. Goodenough†

*The University of Porto, Portugal

†The University of Texas at Austin, TX 78712, USA

Introduction

Complex oxides are essential components of the electrochemical cells that are poised to revolutionize the energy economy of the world. Modern society now runs on the energy stored in a fossil fuel. This dependence is not sustainable. A fossil fuel, once burned, is not recyclable, and the exhaust gases of fossil-fuel combustion not only contribute to global warming, they are also already choking large populations in cities like Beijing in China and New Delhi in India. Since the nuclear option has proven to be a problematic energy source, it has become essential to find a way to return to dependence on the energy that reaches Earth daily from the sun. Converting the sun’s radiant energy and the mechanical energy from wind into electric power is feasible, and the electric power can be transported to distributed collection points, but this power cannot be used unless it is stored. The rechargeable battery stores electric power. Therefore, a priority technical target worldwide is the development of large-scale rechargeable batteries consisting of stacks of identical electrochemical cells that are safe and cost competitive with the energy stored in a fossil fuel. This chapter describes dielectric amorphous-oxide alkali-metal electrolytes that may enable safe, low-cost, large-scale rechargeable batteries of sufficient volumetric density of stored electric power for replacing the air-polluting internal combustion engine powering today’s road vehicles. Such a battery could also be used for distributed storage of electric power harvested from solar and wind energy to supplement the grid. Dielectric amorphous-oxide electrolytes developed at the University of Porto, Portugal have been used at the University of Texas at Austin to develop novel designs for a safe, low-cost rechargeable battery with long charge–discharge cycle life targeted for over 150,000 miles driving and a large volumetric density of stored electric power targeted for a driving range greater than 300 miles with one charge. Fast-moving A+ cations (A = Li, Na) and slower-moving electric dipoles coexist in the dielectric glass electrolytes; this coexistence gives rise to two novel phenomena: self-charge and self-cycling of a rechargeable electrochemical cell. The complex oxides provide a basis for optimism that an all-electric road vehicle powered by batteries charged by solar and wind energy can soon begin to replace the road vehicles now powered by an internal combustion engine running on the chemical energy stored in a fossil fuel.

Rechargeable Batteries

A battery may consist of a single electrochemical cell or contain many identical cells. On discharge, a battery cell delivers electric power P = IV as an electric current I at a voltage V for a time Δt in an external circuit. The cells of a multicell battery are connected in series to give a desired output voltage V and in parallel to give a desired output current I; the stack of cells must be managed so as to give similar power outputs from each cell. Not only the materials of the individual cells but also the cell design determine the cell performance and the cost of multicell management of a large-scale rechargeable battery.

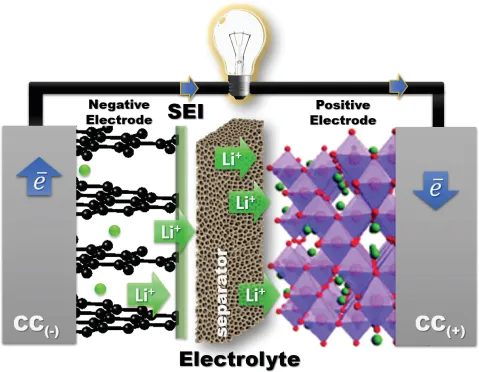

A rechargeable battery cell stores electric power as chemical energy in its two electrodes, a negative electrode (anode) and a positive electrode (cathode) that are separated by an electrolyte, as is illustrated schematically in Figure 1. A liquid electrolyte is absorbed in a porous, flexible separator that keeps the two electrodes apart without being either reduced by the anode reductant or oxidized by the cathode oxidant. The chemical reaction of a cell is normally between the two electrodes and is reversible in a rechargeable battery; the reaction has an electronic and an ionic component. The electrolyte conducts the ionic component inside the cell and forces the electronic component to traverse the external circuit as a current I at a voltage V until the chemical reaction is completed after a time Δt. When the external circuit is open, the cell voltage is Voc = (μA – μC)/e, where μA and μC are, respectively, the electrochemical potentials (Fermi levels) of the anode and the cathode, and e is the magnitude of the electron charge. With a fixed charge and discharge current Idis = Ich, the voltage of the applied charging power Pch = IchVch is Vch > Vdis, which makes the efficiency of power storage 100 Pdis/Pch < 100%. The voltages are as follows:

Figure 1. Battery cell with a liquid or gel electrolyte; the cell contains a negative and a positive electrode, a separator, and a current collector for each electrode. A solid–electrolyte interphase forms on the surface of the negative electrode in contact with the electrolyte where the anode Fermi level is above the electrolyte LUMO; see Figure 2.

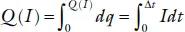

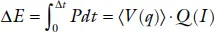

where ηch and ηdis are the resistances to the ionic transfer between the anode and the cathode. The ηchIch is called the overvoltage, the ηdisIdis the polarization. The charge delivered at a fixed current I = dq/dt in the time Δt is the capacity per unit weight or volume

and the total gravimetric or volumetric density of power stored as chemical energy is

where q is the state of charge. The density of stored power ΔE at a desired current I is an important parameter.

During charge and discharge, cations are transferred between the electrode and the electrolyte, so the electrodes change volume. A liquid electrolyte is plastic and, therefore, can retain good electrode–electrolyte contact during the electrode volume changes. Moreover, the resistance to cation diffusion in the electrolyte is Rb = l/σiA, where l/A is the ratio of the thickness to surface area of the electrolyte and σi is the conductivity of the working cation transported by the electrolyte. A σi ≈ 10−2 S cm−1 at 25°C requires, for an acceptably fast charge–discharge, an electrolyte thickness l < 40 μm, where l includes the electrolyte penetration into a thick, porous cathode required for a large Q(I). Therefore, today’s batteries with a large energy density use a liquid electrolyte with a σi ≥ 10−2 S cm−1.

The open-circuit voltage Voc of a cell with a liquid electrolyte is limited by the energy gap Eg = (LUMO − HOMO) between its lowest unoccupied and highest occupied molecular orbital. As is illustrated in Figure 2, if the Fermi level of the anode is above the LUMO energy, the electrolyte is reduced by the anode, and if the Fermi level of the cathode is below the HOMO energy, the electrolyte is oxidized by the cathode. A traditional battery cell uses a strongly alkaline or acidic aqueous electrolyte capable of fast H+ transport (σH > 10−1 S cm−1), but an Eg = 1.23 eV limits the open-circuit voltage to Voc ≤ 1.5 V in a cell with a stable shelf life when charged. This limitation keeps the energy density of the above-mentioned equation too low and the cost too high for a large-scale battery that can compete with the internal combustion engine.

The Li-ion battery of the wireless revolution uses a flammable organic liquid electrolyte with a σi ≈ 10−2 S cm−1. Although fabrication of a cell with an electrolyte thickness l ≲ 30 μm is feasible, there are three problems with the liquid-carbonate electrolyte commonly used: (1) it has Eg ≈ 3.0 eV, (2) the energy of its LUMO is 1.2 eV below the Fermi level of lithium, and (3) plating of a lithium anode during charge results in anode dendrite formation and, on repeated charges, growth across the thin electrolyte to the cathode, which creates an internal short-circuit that ignites the electrolyte. Although ethylene carbonate as an electrolyte additive can create a solid–electrolyte interphase (SEI) layer that passivates reduction of the electrolyte by an anode with a Fermi level above the electrolyte LUMO, the SEI limits the charge–discharge cycle life and lowtemperature operation. Unless the Fermi levels of the two electrodes are within the electrolyte Eg, safety concerns and the cost of too frequent battery replacement make problematic large-scale batteries competitive with the internal combustion engine. Moreover, an air cathode is not feasible for a road vehicle and a sulfur S8 cathode has soluble Li2Sx intermediates in an organic liquid electrolyte that has prevented commercialization. To da...