![]()

1

Introduction

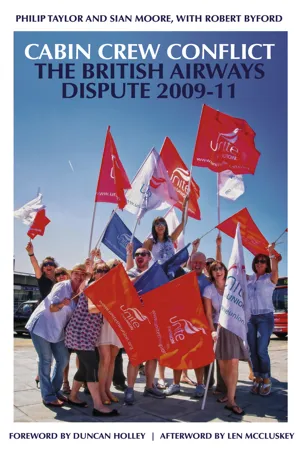

On 22 days during 2010 and 2011 Heathrow Airport presented an unusual sight – row upon row of stationary aircraft with their union jack emblazoned tail-fins standing to attention. British Airways’ Terminal 5 (T5), normally a busy hub of arriving and departing passenger planes, was at a standstill, the most obvious manifestation of acrimonious conflict between British Airways (BA) and its cabin crew, who were members of the British Airlines Stewards and Stewardesses Association (BASSA), part of Unite the Union. Stasis at T5 contrasted sharply with the buzz of activity only a short distance away at Bedfont Football Club, close to Heathrow’s perimeter and BASSA’s operational headquarters on strike days. Here striking cabin crew, their families and their supporters gathered together in mass rallies which resembled carnivals of protest against the draconian actions of British Airways and its Chief Executive Officer (CEO), Willie Walsh. These strike days were the most dramatic events in a protracted dispute that pitched the cabin crew against one of Britain’s most powerful flagship companies in one of the most bitter industrial relations conflicts of recent decades.

The bald statistics are that the dispute involved 22 strike days and cost BA an estimated £150 million in lost revenue.1 The issues of contestation were hugely important, essentially the imposition of major changes to cabin crew’s working conditions which threatened the effectiveness, if not the existence, of BASSA. Indeed, the BA–BASSA dispute and the strikes that were so crucial an element of BASSA’s action raised much broader issues regarding the continued relevance of strike action in contemporary employment relations and the conditions under which groups of workers not noted for their militancy engaged in sustained collective action in defence of their conditions. The dispute also focuses attention on the effectiveness of union strategy and tactics in a neo-liberal era in which workers face belligerent employers and how, through both traditional and innovative methods, they are able to develop their own power resources to counter those of the employers.

More than anything this book tells the story of the dispute from the perspective of and in the words of the cabin crew participants. Indeed, the principal aim that motivated the authors was to write a book for BASSA members, activists and representatives which would provide a meaningful account of events and their involvement in them. From the authors’ initial interactions with cabin crew it was clear that for very many cabin crew, the dispute was a momentous episode and significant event in their lives. While composing a narrative composed of many voices that would be read and welcomed by the participants, the objective, as explained more fully below, was also to deliver an account and analysis that would appeal to a number of audiences simultaneously. One such purpose was to make a contribution to the academic literature on industrial conflict and strikes.

Strikes in the industrial relations literature

There is not the space here for a critical discussion of the extensive literature on strikes. Readers may wish to consult work by Eldridge, Hyman, Shorter and Tilly, Batstone et al., Franzosi and Kelly.2 Godard3 has provided a reflection on the work of Richard Hyman, who has been hugely influential in developing understanding of strikes. For those interested in an overview of the subject excellent chapters can be found in the texts of Williams and of Blyton and Turnbull.4

The overall conclusion from this literature is that strikes are multi-causal social phenomena that are not reducible to a single factor, even though the UK government uses single-principle categories in its recording and measurement of working days lost through strikes.5 The most commonly reported single cause of strikes is pay, yet the issue of pay is often bound up with other conflictual issues integral to the employment relationship, so that union pay claims may be related to the effects of managerial restructuring, to increases in work effort or to changing shift patterns. In the wider literature the distinction is often drawn between the proximate and underlying causes of strikes, a complex interaction to which a single attributed cause cannot do justice. Without pre-empting a full analysis of the roots, sources and immediate triggers of BASSA’s action, underlying causes may be identified in the changing political economy of civil aviation, industry-wide deregulation and liberalisation, intensified market competition driving industry-wide cost (particularly labour cost) reduction and the concomitant compulsion to restructure operations and to dilute ‘legacy’ terms and conditions. If these might be seen as macro-level factors, then operating at another level might be firm level factors, in this case British Airways’ market and product strategies and its conflictual tradition of industrial relations and people management, which must be considered alongside numerable factors relating to union capacity, organisation, leadership, resources, orientation and preparedness to act. Then, the proximate or trigger causes intercede, in this case British Airways’ determination to impose thoroughgoing change to employment contracts, working conditions, collective bargaining and union influence. The multi-causal and multi-layered nature of the BASSA strike is explored in Chapter 2 and described by cabin crew participants in the following chapters.

In the field of industrial relations it is widely acknowledged that there are three frameworks. The first of these, the unitarist framework, sees strikes as the result of poor communication or the actions of agitators or troublemakers and, as such, can be easily dismissed as lacking explanatory purchase. If the second, the pluralist framework, emphasises the institutions and processes of collective bargaining and recognises conflict as legitimate, it is the Marxist framework that provides the most convincing general theory of strikes. Rooted in the theory that society is divided into antagonistic classes (and thus employment relationships), it provides the most effective analytical framework. Such a verdict is true not just in the narrow sense of explaining why collective bargaining might break down, but also in the broader sense of understanding that the basis of action is the outcome of the existence of distinct worker interests and the impulse to organise collectively.

Two important themes from the literature help locate the BA–BASSA. First, there has been universal acknowledgement that there is a relationship (often highly complex) between the incidence of strikes and broader economic conditions.6 When unemployment is low, workers tend to be more confident and more likely to pursue their demands through striking but, equally, in these circumstances employers may be more likely to concede to union demands in order to avert strike disruption.7 Conversely, when unemployment is high, workers may be less confident but, with employers’ commitment to cost-cutting, workers may have more reason to believe they have no choice but to withdraw their labour. While macro-economic conditions exercise a general influence on strike activity, it is important to acknowledge the possibility of variation, for at the level of sector, company or even plant or region, broadly similar economic conditions may lead to differential outcomes. The BA–BASSA strike took place in the wake of financial crisis and during economic recession, but in a period of high employment and against a general backdrop of depressed strike activity.

The second theme is the attempt to identify strike-prone industries and to explain the reasons for this pattern of behaviour. Kerr and Siegel8 argued that groups of workers, including miners, dockers, sailors and loggers, who formed powerful localised and/or occupational communities that were strongly unionised, were most strike-prone. This theory that workers at society’s margins were most likely to strike was potently challenged by Shorter and Tilly.9 They argued that the most strike-prone were to be found in the big urban centres with all their occupational diversity, rather than in isolated communities. Acknowledging this debate, how might the BA–BASSA strike be regarded? There is a sense in which the term community is meaningful, for British Airways’ crew certainly defined themselves as a community in occupational, social and solidaristic terms (see Chapters 4–6). This powerful notion of community was the wellspring of collectivism which underpinned the strike and which BASSA was able to tap into.10 For cabin crew, as for other groups of workers, the construction and lived experiences of community were crucial for mobilisation and sustaining collective action.

The strike process

Lyddon has observed that attempts to analyse the strike process are relatively uncommon.11 A classic study by Hiller12 does provide a valuable account of a ‘processual model of strikes’13 and is based on the collection of data over an extended time frame. Hiller identified several separate processes of a strike; organisation, mobilisation, maintaining group morale, controlling strike-breakers, neutralising employers’ manoeuvres, shaping public opinion and demobilisation.14 The book’s introduction suggested that strikes consist of ‘a cycle of typical events which take place in a more or less regular and predictable way’,15 observations that must be qualified by the fact that these identifiable processes do not necessarily occur in fixed order and might overlap. For example, the historical shift from continuous to non-consecutive episodes of strike activity (one day or two day strikes) in recent UK industrial relations, in part due to legal constraint, challenges this notion of a regular order to the strike process.

So, notwithstanding similarities in the processes and common characteristics, no two strikes are identical. Gouldner, in his seminal study of a ‘wildcat strike’ (a strike not called or sanctioned by a union leadership), made a universally valid point: ‘A “strike” is a social phenomenon of enormous complexity which, in its totality, is never susceptible to complete description, let alone complete explanation.’16 An important element in this complexity is what Eldridge17 described as ‘vocabularies of motive’, the ways that workers and their union frame and rationalise their actions.18 Chapters 3–6 of the present volume are peppered with these ‘vocabularies of motive’, particularly the crew’s conviction that their actions were justified because British Airways had transgressed what was morally right as much as the fact that company’s actions posed a very material threat to their conditions.

It is remarkable that few studies of strike action have placed at their centre the dynamics of strikes and the meanings of action as expressed by those workers directly involved in them.19 Exceptions include Kars’s account of a 4-month strike by women workers for union recognition at a mill in Saylor, near Chicago.20 He revealed how participants were transformed by the experience, a major theme of this book (Chapter 6). A real strength of Kars’s work lies in the systematic interviews conducted in the strike’s aftermath with the union leadership and with samples of rank-and-file participants and ‘fence-sitters’, although those with non-strikers had to be abandoned because of heightened emotions. Consequently, the narrative contains extensive quotes on organising tactics, on songs, on workers’ still fresh recollections of the picket lines, their experiences and broader views. A significant general conclusion, of salience to the BA–BASSA dispute, was that ‘conflict establishes the identity of groups within a social system by strengthening group consciousness’.21

A study of the seven-week unofficial strike by 8,500 glassworkers at Pilkingtons in St Helens (Lancashire) in 197022 was (and remains) hugely significant since as the authors, Lane and Roberts, observe until their book ‘nobody [had] ever attempted a full-scale study of a strike in the UK’.23 Key to understanding the strike’s dynamics was workers’ disillusionment with the General and Municipal Workers Union which prompted them to set up a rank-and-file strike committee. This development contrasts, of course, with the BA–BASSA case which was an official dispute that saw, despite tensions at the outcome (Chapter 6), strong bonds of unity between BASSA leaders and members. Nevertheless, Lane and Roberts emphasise certain outstanding and common features of strikes that do have relevance to the BA–BASSA dispute. Strikes are ‘an emotional explosion of discontent’, inflamed by the accumulation of grievances. Further, their occurrence reflects the efficiency (or otherwise) of the machinery for the settlement of grievances and they tend to happen when a group of workers hold a strategic...