![]()

Chapter 1

Cosmic γ-Rays and Atmospheric Showers

1.1.Cosmic Discovery: Through Space and Time

From the early 17th century when Galileo Galilei began experimenting with “perspective glasses”, brought to Venice in 1609 by Dutch merchants, mankind has been on an epic journey of cosmic discovery. Combining pairs of such glasses, Galileo fabricated an instrument capable of significant image magnification, which he immediately applied to observations of the night sky. Soon to be referred to as a telescope, the device made it possible to conduct detailed visual examination of the moon, planets, comets, stars and in the process, heralded the birth of observational optical astronomy. Over the course of the next four centuries, optical telescope design evolved in terms of light-gathering power and magnification capability, enabling greater sensitivity observations of cosmic phenomena in what we now refer to as the visible spectral region, corresponding to that of the human eye. By the 19th century, following invention of the photographic plate, optical astronomy attained the powerful capability of integrating incident visible light and capturing permanent images. Here, for the first time, was the ability to exploit photographic sensitivity beyond that attainable simply with visible light. In effect, experimental astronomy now embraced both near infrared and near ultraviolet regions of the spectrum.

However, it was not until the early 20th century that the ubiquity and dominance of the optical window was to be challenged as a second channel of cosmic discovery emerged, albeit in a somewhat indirect manner. It is generally acknowledged that cosmic radiation studies began in the early 1900s based on investigations into the conductivity of air and the apparent slow discharge with time of initially charged electroscopes. One suggested explanation of the discharge phenomenon was the presence in the atmosphere of some unknown, penetrating radiation. Based on flying charged electroscopes high into the earth’s atmosphere, Hess, in 1912 [3], found strong evidence that the rate of electroscope-discharge increased significantly above 2000 m altitude, verifying the presence of a hitherto unknown isotropic radiation of great penetrating power and apparently of cosmic origin. At the time it was supposed that the radiation was some form of high-energy γ-radiation. Over the first half of the 20th century, cosmic-ray research was to become an exceedingly important new investigative modality which, together with other emerging information channels such as radioastronomy, greatly expanded our understanding of the cosmos.

Progress in experimental astronomy and astrophysics is generally intermittent, frequently serendipitous and almost never predictable with any degree of confidence. In his interesting and influential 1981 book Cosmic Discovery: The Search, Scope and Heritage of Astronomy, Martin Harwit [1] charted how our understanding of the universe has developed and evolved since the time of Galileo. While emphasising that advances are mostly the result of incremental improvements and adaptations of existing technologies, sometimes completely new detector technologies may emerge from novel basic discoveries in solid-state physics, materials science or advances in optics, leading on to unanticipated breakthroughs of ground-breaking relevance.

In similar spirit, the broad arc of astronomical technological progression accomplished since 1960 has recently been reviewed by Appenzeller [2] from the perspective of how new technologies inspired new astronomical disciplines and novel technical tools as researchers sought to access regions of the electromagnetic spectrum beyond the heretofore traditional radio and optical domains. Occasionally, as with space sciences, some new and essential enabling technology has to emerge (rocketry and satellites) before a new photon energy domain becomes accessible to exploration and exploitation. Angular resolution improvements in optical and infrared astronomy over much of the latter part of the 20th century have been spectacular. The pioneering Hubble Space Telescope was a major advance, while the development of speckle and adaptive-optics imaging in combination with fabrication of lightweight mirrors has given rise to dramatic improvement in ground-based angular resolution capability. Since the pioneering development of radioastronomy in the 1930s, flux sensitivity improvements of 12 orders of magnitude have been attained at radiofrequencies.

The rich scientific potential of probing the non-thermal universe at photon energies in the X-ray and γ-ray energy domains, with the prime objective of possibly discovering emitting point sources, was to become a major preoccupation for a growing community of experimentalists from the late 1950s onwards. Despite initial discouraging theoretical predictions concerning the detectability of possible celestial point sources of X-ray emission, by the mid-1960s, the field of extra-solar X-rays had successfully made a number of important detections using detectors carried aloft employing either balloon or rocket launches. In contrast, early ground-based TeV (1012 electron volts) γ-ray detectors of the 1960s and 1970s proved unsuccessful, lacking sufficient sensitivity to deal with an overwhelming cosmic-ray background and by the mid-1970s this avenue of experimental research was essentially to become moribund. More encouragingly, with the advent of satellite instrumentation beginning early in the 1970s, exciting new possibilities for observations from space became a reality, not only in optical astronomy, but also for infrared, ultraviolet, X-ray and low-energy γ-ray regions of the electromagnetic spectrum. For γ-ray energies in the range from 30 MeV to 5 GeV, the COS-B satellite (launched in 1975) had sufficient angular resolution to be able to resolve individual cosmic sources, effectively establishing the field of low-energy γ-ray astronomy. Beginning in 1991, the Compton Gamma Ray Observatory (CGRO), with four instruments spanning six decades of the electromagnetic spectrum from 20 keV to 30 GeV was to operate for nine years. An outstandingly successful mission, it was to perform the first sensitive survey of the sky in the low-energy γ-ray domain, while also making fundamental discoveries concerning some of the most energetic phenomena in the universe, including γ-ray bursts, supernovae, pulsars, quasars and black holes. The mission also contributed to a better understanding of galactic structure and the underlying dynamics. Encouragingly, TeV γ-ray astronomy was to re-emerge in 1978 as a potentially viable research discipline. New possibilities, directed at reduction of the unwanted cosmic-ray background, offered grounds for optimism and gradually many new investigators engaged with the challenge, spurred onwards by the exciting progress and important discoveries of groups operating in the cognate X-ray and low-energy γ-ray domains.

1.2.TeV γ-Ray Astronomy: A Century in the Making

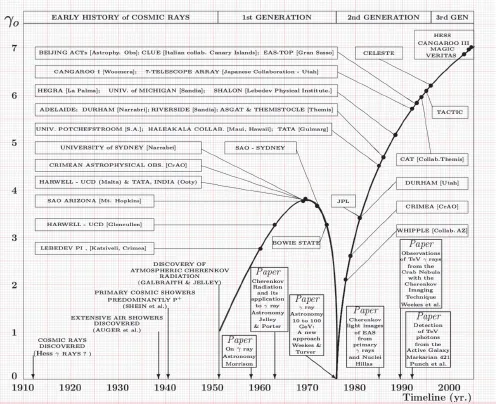

It is occasionally mistakenly imagined that TeV γ-ray astronomy began with developments undertaken during the final decade of the 20th century. While the first convincing accomplishments date approximately from that interval, Fig. 1.1 depicts a much longer evolutionary timeline. The ordinate γo portrays some notional undefined proxy-parameter of community confidence in possibly establishing TeV γ-ray astronomy, the abscissa indicates developmental timeline in calendar years. The timescale embraces three distinct generations of TeV detector development (1st, 2nd and 3rd), preceded by the long era of classic research in cosmic radiation physics, itself embracing almost the entire first half of the 20th century. Important milestones spanning that era were the discovery of cosmic rays in 1912, the discovery of Extensive Air Showers (EAS) in 1938, the recognition in 1941 that primary cosmic rays were predominantly protons and, critically, the fundamentally important discovery in 1952 of Cherenkov radiation produced by EAS charged particles in the earth’s atmosphere.

Figure 1.1 also identifies the many experimental research groups and collaborations that, over the latter half of the 20th century, contributed to the development of high-energy γ-ray astronomy in the energy range from 1011 to 1013 eV. Marker identification dots peppering both segments of the plot correspond to either the startup dates or the attainment of first lighta of the many experiments individually identified within the annotated text boxes. Immediately following the discovery of atmospheric Cherenkov radiation, some unsuccessful attempts were made to find point sources of cosmic rays by using primitive technology, but it was not until the late 1950s and early 1960s that the first purposeful search for point sources of γ-rays was undertaken. Finally, Fig. 1.1 incorporates thumbnail placeholders pointing to six noteworthy papers, the four earliest being fundamentally influential in charting the route to establishing the discipline, the latter pair marking the discovery of the first two TeV sources.

Fig. 1.1. BIG GAMMA — timeline. The ordinate γo represents some notional undefined proxy-parameter of community confidence in possibly establishing TeV γ-ray astronomy, the abscissa represents calendar year. The first segment of the plot exhibits a slow rise peaking around 1970 followed by a rapid decline, summarising 1st-generation failure. The second plot segment reflects a continuously rising curve corresponding to the ultimately successful 2nd and 3rd generations (see text for notational details).

The great challenge of TeV γ-ray astronomy had been to find an effective strategy for rejection of an overwhelming unwanted background of charged cosmic rays (predominantly protons) that completely dominates the small fluxes of cosmic γ-rays making the source discovery extremely difficult. Recognised as such from the very early 1960s, exploratory 1st-generation Cherenkov instruments, spanning a decade and a half of development (1960 to 1975), all failed to uncover a workable strategy despite the optimism, ingenuity and dedicated application of a handful of pioneers. However, following a short hiatus, there emerged the 2nd generation of Cherenkov detectors during the late 1970s and the 1980s, where optimisation of system-design parameters was strongly driven by Monte Carlo simulations of shower development with particular attention being paid to inherent differences between electromagnetic and hadronic background showers. Simulations had a seminal influence on the emergence of two quite different detector design philosophies, each predicting that good flux sensitivity might be combined with good angular resolution. The first approach favoured imaging, whereby a picture of the shower image is captured in real-time and subsequently parameterised offline. Through comparison of the real-data parameter distributions with those of the γ-ray and hadronic shower simulations, it appeared possible, in principle, to reject background and enhance the desired γ-ray content of any particular set of observations. The second approach involved wavefront sampling whereby the EAS front might be sampled by a number of reasonably spaced Cherenkov receivers at ground level and by exploiting fast timing and coincidence detection techniques, it might prove possible to selectively enhance detection of γ-rays over hadrons, based on improved angular resolution.

A decade and a half (1978–1992) of painstakingly incremental progress led to successful development of the IACT (Imaging Atmospheric Cherenkov Telescope) technique, by the international Whipple collaboration based at Mt. Hopkins Observatory, Arizona. By 1992, the first galactic and the first extragalactic TeV sources had been detected by the collaboration at unassailable levels of statistical significance — the Crab Nebula in 1989, and Markarian 421 in 1992. Thereafter, the IACT technique was to become the dominant modus-operandi of most subsequent atmospheric Cherenkov instruments commissioned during the 2nd and 3rd generations of instrumental design. An important aspect of that early maturation phase was the successful perfecting of stereoscopic imaging as exemplified by the HEGRA collaboration during the final decade of the 20th century.

This very detailed historical review chronologically traces the emergence of TeV γ-ray astronomy through the latter half of the 20th century. Major focus is on the evolution of IACT technique, emphasising concepts, ideas and important milestones underpinning its development. While the storyline is mainly presented from the perspective of the Whipple collaboration’s experiences, the commentary attempts to be both balanced and objective in presentation of the broader community’s contemporaneous findings at TeV energies and, where relevant, at PeV energies. The interval 1978 to 1992 was very important as during that time the population of TeV researchers slowly expanded, funding became easier and new initiatives were explored and evaluated. Cosmic-ray conferences, together with dedicated γ-ray workshops, proved important in appraising progress and for that reason have been liberally referenced here and quoted from in order to inform the narrative, since they accurately captured the spirit and mood of the field at critical points along the timeline. Over the 15 years in question, progress was to ebb and flow and proceedings of both conference and workshop sessions have proved invaluable in clarifying contentious issues such as the appropriateness (or otherwise) of statistical tests employed in routine data analysis, the fundamental importance of γ-ray and proton shower simulations, the merits of various background rejection strategies, the fidelity of individual detector calibration methodologies and most importantly, ongoing objective appraisal of a growing confidence in the field, as reflected through rapporteur reports and invited review papers, both theoretical and experimental.

Considerable coverage is also presented here of the ongoing preoccupation during the 1970s and 1980s with X-ray binary objects (XRB). Vast amounts of observational time, together with scarce financial and manpower resources, were lavished on this class of object. Evidence as to the veracity and statistical robustness of many reported detections of XRBs at TeV and PeV energies (also by a number of underground detectors), enlivened many conference and workshop sessions, as confusion, contradiction and chaos were sown far and wide. The Whipple collaboration eventually debunked XRBs as sources of TeV γ-rays, but only after establishing that the IACT strategy was unequivocally beyond reproach based on the successful detection of the Crab Nebula. This was an important and frequently overlooked bonus feature of the imaging technique, since it demonstrated beyond doubt that if XRBs were emitting any form of high-energy particles (unlikely) then such emission was most certainly not due to TeV γ-rays.

Closing chapters of this book examine, with the benefit of much hindsight, the relative insensitivity of 1st-generation detectors and also address the question as to why Whipple’s development of the IACT technique took about 15 years from conception to ultimate establishment of the first couple of TeV sources. Provocatively, the question as to whether imaging might have been possible at some earlier point along the timeline is also addressed. Finally, a very brief overview is presented of the status of TeV γ-ray astronomy in 2019, a success story far in excess of the very modest expectations of the discipline’s pioneers.

1.3.Photons or Ionising Particles?

In 1900, it was believed that air was a perfect insulator. However, experiments conducted by C.T.R. Wilson on the nature of electrical conductivity of air exhibited minor inconsistencies between theory and experiment. Ionic currents were observed to persist in a se...