One bright Saturday morning in March 2013 I travelled to an affluent and attractive suburb of north London to meet with Hayley,1 a 38-year-old television and radio producer who, two-and-a-half years earlier, made the decision to freeze her eggs. Hayley, a warm and friendly woman dressed in an oversized grey woollen jumper welcomed me to her spacious and thoughtfully styled flat where we talked for several hours about her hopes and desires for motherhood, the difficulties she had encountered in finding the ‘right’ partner and her experience of drawing on what was at the time a very novel form of assisted reproductive technology. Hayley is in good company; between 2010 and 2016 the numbers of women undergoing egg freezing soared, with data from the UK Fertility Regulator, the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA), reporting a 460% increase in the number of egg freezing cycles performed (HFEA, 2018a, 2018b). It appears that whilst growing numbers of women and couples may be choosing not to have children (Ashburn-Nardo, 2017), motherhood remains a life goal and expectation for many women, and some are willing to spend a significant amount of time and several thousand pounds on a technology that may increase their chance of being able to conceive, carry and give birth to a genetically related child in the future.

This introductory chapter seeks to situate the new technology of egg freezing within its specific social, economic and technological context. It examines how socio-cultural changes in the lives of women have reshaped the process, as well as experience, of relationship and family building and identifies how these changes have come into conflict with the immovable realities of women’s natural fertility. In exploring the possibilities offered by new reproductive technologies more widely, this chapter begins to examine the promissory potential of egg freezing and provides a discussion and justification for the precise nomenclature that is adopted throughout this book. In introducing the technology, this chapter also explores key issues related to egg freezing ‘success rates’, the subject of access and the cost of the procedure, and the risks associated with this form of reproductive technology. The chapter then concludes with a brief discussion of the research and scholarship which underpins this text and provides an overview of the book as a whole.

1.1. Socio-cultural Context

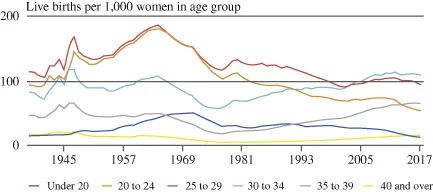

The last 40 years have seen a persistent shift towards later childbearing in many Western countries including the United Kingdom (Kreyenfeld, 2010; Ní Bhrolcháin & Toulemon, 2005). During the 1970s, women in England and Wales were on average 26 years of age at the birth of their first child; however, by 2016 this had increased to 28.8 years (ONS, 2018). As Graph 1.1 indicates, the number of women having children at a younger age (under 20, 20–24 and 25–29) has significantly declined since the 1970s, and in the same period the number of women having children at an older age (30–34, 35–39 and 40 and over) has increased. Indeed, prior to 2003 more babies were born to women aged 25–29 than any other age group; however, women aged 30–34 now have the highest rate of fertility (ONS, 2015).

Graph 1.1:.Age-specific Fertility Rates (England and Wales, 1938–2017). Source: Office for National Statistics, 2018, used with permission.

When the total fertility rate fell in the United Kingdom for a fifth consecutive year in 2017, decreased fertility rates were observed across every age group except for women aged 40 and over where the rate increased by 1.3%, reaching the highest level since 1949. This increase is part of a general trend which has seen the fertility rate of women aged 40 and over more than treble since 19912 (ONS, 2014). Whilst this trend towards later motherhood has been most significantly observed in Western societies, a shift towards delayed and older motherhood has also been identified in new and developing economies such as India, China and Latin America (Allahbadia, 2016; Sobotka & Beaujouan, 2018).

Delayed motherhood and the shift to later childbearing have been attributed to a wide range of social, economic, personal and relational factors. These include the increased reliability of methods of contraception; changing social norms related to the timing of parenthood; women’s increased participation in higher education and the labour force; the normalisation of multiple partnerships prior to marriage; difficulties in finding a partner with whom to pursue parenting; perceptions of personal readiness; rising costs of living and childcare; as well as economic instability and market uncertainty (Chabé-Ferret & Gobbi, 2018; Daly, 2011; Daniluk & Koert, 2017; Mills, Rindfuss, McDonald, te Velde, & ESHRE Reproduction, & Society Task Force, 2011). Indeed, improvements in population health, advances in medical technology, and access to contraception and abortion have meant that many women and men in the global north now have an unprecedented level of control over their fertility. Furthermore, should they wish to have children, they can exert significant influence over the timing of parenthood (Lemoine & Ravitsky, 2015; Lowe, 2016). However, when the time comes to try and create their families, many women, men and couples find they have experienced only the illusion of reproductive control and are unable to conceive without medical intervention (Earle & Letherby, 2007).

Around one in six couples in the United Kingdom have difficulties in conceiving, and for many this is a highly stressful, emotionally difficult, isolating as well as stigmatising experience with the potential for long-term effects even if they do eventually become parents (Cox, Glazebrook, Sheard, Ndukwe, & Oates, 2006; Wirtberg, Möller, Hogström, Tronstad, & Lalos, 2006). Prior to the advent of assisted reproductive technologies the experience of infertility was something the sufferer was forced to live with which, whilst was disappointing for many, was ultimately unchangeable (Earle & Letherby, 2002). However, following the development of in vitro fertilisation (IVF) by UK scientists Robert Edwards, Patrick Steptoe and Jean Purdy, and the birth of the first IVF baby Louise Brown in 1978, there was a shift from the social problem of involuntary childlessness to the medical problem of infertility (Becker & Nachtigall, 1992). This shift, and the way that medicalised fertility treatment has become increasingly normalised and routinised, not only in the clinic but also among wider publics, reflects how the social and private lives of social actors have become increasingly dominated by biomedicine (Clarke, 2010).

It is estimated that over eight million babies have been born worldwide from IVF technologies. In the United Kingdom the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) suggests that women should be offered up to three cycles of IVF funded by the National Health Service (NHS), subject to certain criteria. However, in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, access to NHS-funded fertility treatment is overseen by local clinical commissioning groups (CCGs), and as few as 12% of CCGs follow this national guidance with many offering patients only one cycle of IVF or in some cases none at all (Fertility Fairness, 2017). This approach to the rationing of IVF treatment means that depending on where a person lives, access to IVF and the conditions of this access varies considerably. In 2016, 41% of IVF treatment cycles were funded by the NHS, leaving the remaining 59% of treatments to be privately funded. The cost of a cycle of IVF varies across the country and by the needs of individual patients and couples but may cost upwards of £5,000 per cycle. Thus, medicalised fertility treatment is beyond the reach of many (Bell, 2009).

Despite the high financial as well as emotional costs of medicalised fertility treatment, almost three-quarters of IVF cycles do not result in a live birth (HFEA, 2016). The birth rate per embryo transfer (PET) for all fresh cycles of IVF in the United Kingdom in 2016 was 21%. However, when broken down by age, birth rates vary considerably, with women under 35 having the highest birth rate PET (29%) and women over the age of 44 having the lowest (below 15%) (HFEA, 2016). As such, it is worth noting that even in younger patients, IVF has only a modest success rate which sees less than one in three couples with a ‘take-home baby’ after one round of treatment. Nevertheless, stories of miracle IVF babies and IVF success continue to abound in all quarters of the media, leading many to overestimate the efficacy of the technology (Chan, Chan, Peterson, Lampic, & Tam, 2015; Lucas, Rosario, & Shelling, 2015). Furthermore, despite its seemingly ubiquitous nature, fertility treatment is not risk free (Kamphuis, Bhattacharya, Van Der Veen, Mol, & Templeton, 2014); yet there remains an expectation that individuals and couples who struggle to conceive will want, and will draw upon, new reproductive technologies in order to build their families (Bell, 2017; Sandelowski, 1991).

Since the birth of the first IVF baby over 40 years ago, the number of technologies, treatments and procedures to assist in the process of creating healthy human life has expanded significantly and the UK fertility industry is now estimated to be worth £320 million (Risebrow, 2018). This expansion of the fertility industry has not only enabled many heterosexual couples to overcome barriers to parenthood but, through technologies of reproductive donation as well as surrogacy, has seen the emergence and increased visibility of alternative family forms such as lesbian mother families, gay father families and families headed by single mothers by choice (Nordqvist & Smart, 2014; Norton, Hudson, & Culley, 2013; Zadeh, Ilioi, Jadva, & Golombok, 2018). Furthermore, new developments in genetic screening and mitochondrial donation have also enabled people with serious inherited diseases in their family to have children of their own, safe in the knowledge that they will not be passing on the disease to their offspring (Dimond & Stephens, 2018; Herbrand, 2017). Technologies of egg donation have also enabled some women of advanced maternal age, who have reached the end of their reproductive lives, to experience pregnancy, birth and motherhood (Osazee & Omozuwa, 2018). However, the age of a woman at the time of trying to conceive, either naturally or via medicalised fertility treatment, is universally recognised as one of the best predictors of a future live birth (Balasch, 2010; Dunson, Colombo, & Baird, 2002).

1.2. Age and Fertility

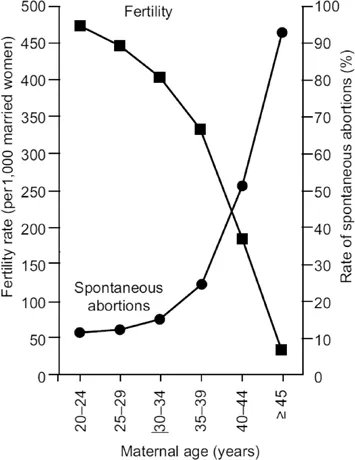

A female foetus at 20 weeks has between 6 and 7 million eggs; however, at the time of birth her egg reserve will have already decreased by several million and she will continue to ‘lose’ eggs throughout her life. This loss occurs not only via ovulation and menstruation but also through the process of atresia, which sees the degeneration of ovarian follicles that do not ovulate during the menstrual cycle. This means that by puberty a girl has 300,000–500,000 eggs remaining, dropping to 25,000 at age 37, and by the time she enters menopause she may have as few as 1,000 eggs left, the majority of which will be of very low quality. This process of fertility decline is believed to occur throughout a woman’s lifetime with a slight increase of the rate of decline beginning after she is 32, with a further pronounced and more accelerated loss of eggs occurring after 37 years (American College of Obstetricians & Gynecologists, 2014). As a woman ages, the quality and quantity of her eggs decline, which together has a significant effect on her ability to spontaneously conceive and carry a healthy pregnancy to full term (Utting & Bewley, 2011). Indeed, research has shown that as a woman gets older the chance of getting pregnant declines and the likelihood of a pregnancy ending in a miscarriage increases (Balasch & Gratacos, 2012; Heffner, 2004; Nybo Andersen, Wohlfahrt, Christens, Olsen, & Melbye, 2000) (see Graph 1.2), and by the time a woman is 40, some evidence has suggested that the risk of experiencing a miscarriage may overtake the chance of a live birth.

Graph 1.2:.Fertility and Miscarriage with Advancing Maternal Age. Source: Reproduced with permission from Heffner (2004), © Massachusetts Medical Society.

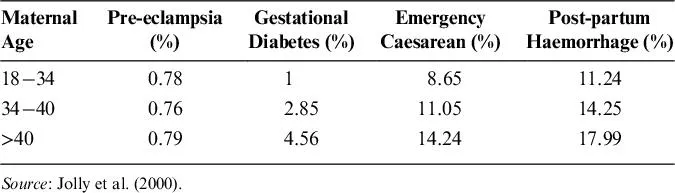

Women who are pregnant at the age of 35 and older are routinely described in medical literature as ‘older mothers’ and are believed to be at an increased risk of many other complications throughout pregnancy and birth (see Tables 1.1 and 1.2), including gestational diabetes (Hemminki, 1996; Jolly, Sebire, Harris, Robinson, & Regan, 2000; Joseph et al., 2005), placenta praevia (Williams & Mittendorf, 1993), placenta abruption (Utting & Bewley, 2011), emergency caesarean section (Rosenthal & Paterson-Brown, 1998; Tough et al., 2002), chronic hypertension (Gosden & Rutherford, 1995), pre-eclampsia (Ziadeh & Yahaya, 2001) and post-partum haemorrhage (Jolly et al., 2000). Additional risks to children born from older mothers include an elevated risk of birth defects or genetic/chromosomal abnormalities (see Table 1.1), including trisomy 21, which results in Down’s syndrome. By comparison, whilst some research has shown a link between advanced paternal age and negative health outcomes seen in children, these risks are less pronounced and occur at a much older age (Balasch, 2010; Bray, Gunnell, & Davey Smith, 2006; Hook, 1981; Toriello, Meck, & Professional Practice, & Guidelines Committee, 2008).

Table 1.1:.Risk of Down’s Syndrome and Chromosomal Abnormalities at Live Birth according to Maternal Age.

Maternal Age at Delivery | Risk of Down’s Syndrome | Risk of Any Chromosomal Abnormality |

20 | 1/1,667 | 1/526 |

25 | 1/1,200 | 1/476 |

30 | 1/952 | 1/385 |

35 | 1/378 | 1/192 |

40 | 1/106 | 1/66 |

45 | 1/30 | 1/21 |

Source: From Heffner (2004).

Table 1.2:.Risks to Mothers in Pregnancy and Childbirth.

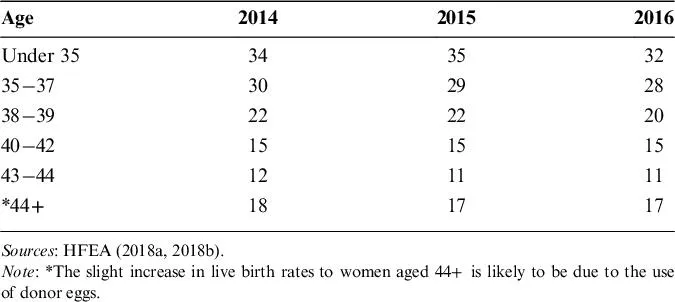

The causes of infertility in women and men are multiple and largely known (see NICE, 2013 for further discussion); however, in up to 25% of cases no reason for infertility can be ascertained and the term ‘unexplained infertility’ is used (NICE, 2013). Although younger women can experience ‘unexplained infertility’, research has linked this to the age of women at the time of trying to conceive (Maheshwari, Porter, Shetty, & Bhattacharya, 2008). Whilst IVF technologies can help some women and couples experiencing unexplained infertility to conceive much wanted children, the success rates of IVF in older women remain low (see Table 1.3). Therefore, if a woman is unable to conceive via IVF using her own eggs due to problems with egg quality or quantity, she may be counselled to consider egg donation. This would see her attempt conception using eggs donated by another, sometimes younger woman.

Table 1.3:.Live Birth Rate Per Treatment Cycle (2014–2016).

The use of donor eggs in IVF has been shown to increase the chance of a live birth in older women as the capacity to conceive and carry a pregnancy to term has been shown to be affected primarily by the age of a woman’s eggs, not the age of her womb (Navot et al., 1994).

1.2.1. Awareness of Age-related Fertility Decline

Whilst IVF and egg donation can enable some women to have children, these technologies cannot undo or redeem the fertility lost to the process of reproductive ageing (Alviggi, Humaidan, Howles, Tredway, & Hillier, 2009; Leridon, 2004). However, despite the significant consequences of age-related fertility decline (ARFD), scientific knowledge on this topic has been slow to develop and arguably even more slowly disseminated (Mac Dougall, Beyene, & Nachtigall, 2012). A substantial body of research has indicated that both men and women may lack a detailed understanding of the relationship between age and fertility, particularly as it relates to the fertility of women. Indeed, whilst a systematic review of 41 studies which quantitatively measured knowledge of ARFD identified a general awareness of fertility decline, as well as a good understanding of when fertility was at its peak, it found that the fertility knowledge of men and women was often insufficient particularly when it came to identify the time in the lifecourse when female fertility began to decrease more markedly (García, Brazal, Rodríguez, Prat, & Vassena, 2018). Similar research findings have been identified by Wyndham, Marin Figueira, and Patrizio (2012) who noted that whilst men and women most often have a general awareness that fertility declines with age, there is less understanding of the extent or rate of this decline or the time of its onset.

Whilst women and men with higher levels of education are more likely to delay childbearing, studies examining the awareness of ARFD in student populations in Sweden, (Lampic, Svanberg, Karlstrom, & Tyden, 2006; Tydén, Svanberg, Karlström, Lihoff, & Lampic, 2006), Israel (Hashiloni-Dolev, Kaplan, & Shkedi-Rafid, 2011), Denmark (Sørensen et al., 2016) and Canada (Bretherick, Fairbrother, Avila, Harbord, & Robinson, 2010) have found participants to significantly overestimate a woman’s capacity to become pregnant at an older age, as well overestimate the age at which a woman’s fertility most significantly declines and the probability of achieving a child from IVF treatment at an older age. Similar findings have also been identified in studies of midwifery students (Chelli, Riquet, Perrin, & Courbiere, 2015), obstetrics and gynaecology residents (Yu, Peterson, Inhorn, Boehm, &...