- 273 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Funerary Practices in the Netherlands

About this book

In contextualizing the Dutch funerary practice in its wider legal, national and local governance framework, this book describes the historical context for current practices, provides data on trends in burial and cremation, and examines recent developments including natural burial, increasing religious diversity and changing national legislation.

Chapters provide an overview of funerary history and contemporary practice, alongside photographs, charts and tables of key information. Topics explored include: the death care industry; the Corpse Disposal Act; a typical funeral including funeral costs and insurance; cemetery and crematorium provision; and, the practices, technicalities and legalities of burial and cremation. The book also analyses and illustrates the commemorative practice of public mourning events related to World War II, the Holocaust and the MH17 plane crash.

This book provides a broad frame of reference on funeral practices, making it a useful resource for academics, policy makers and practitioners interested in the historic, legal, technical and professional aspects of the funerary industry.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Funerary Practices in the Netherlands by Brenda Mathijssen,Claudia Venhorst in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Customs & Traditions. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

THE NETHERLANDS: AN INTRODUCTION

1.1. OVERVIEW

The Netherlands, called Nederland in Dutch, is a rather small and densely populated country in North Western Europe. It borders Germany at the east and Belgium to the south. The country is often (incorrectly) referred to as ‘Holland’, the historic name of just two of the current 12 provinces: Noord-Holland, Zuid-Holland, Utrecht, Zeeland, Brabant, Limburg, Gelderland, Overijssel, Flevoland, Drenthe, Friesland and Groningen. Within the provinces 355 municipalities can be found, forming the lowest level of governance. The municipality provides services and policy at a local level. Together with three island territories in the Caribbean (Bonaire, Saint Eustatius and Saba), these provinces make up the Kingdom of the Netherlands (see map on page xxi).

The Netherlands is a parliamentary constitutional monarchy. Its central government is seated in The Hague and Amsterdam is its capital city. It is part of the European Union, the Euro-zone and the Schengen Area. It qualifies as a welfare state which provides universal healthcare, public education, infrastructure and social benefits. Nederland or ‘lower land’ refers to the fact that more than a quarter of the country is situated below sea level, and the rest a mere metre above. The landscape is moulded by canals, rivers and lakes. The fight against water is of all times and ongoing, influencing many day-to-day practices. High groundwater levels often complicate the burying of the dead, demanding innovative and costly solutions and putting pressure on available burial space in certain areas.

With 17.2 million inhabitants on 41,500 km2 (of which 33,700 km2 actual land), the Netherlands is one of the most densely populated countries in the world. Well over 90% of the population is living in cities. The four largest cities – Amsterdam, Rotterdam, The Hague and Utrecht – and their surrounding areas form the so-called Randstad metropolis: the densely populated (8.2 million inhabitants in 2018) economic heart of the country. The mixed-market economy is among the top economies in the world, and the Netherlands is the world’s second largest exporter of food and agricultural products due to intensive and innovative agriculture.

1.2. PILLARS AND POLDERS

The Netherlands was long deeply divided along religious lines. From the nineteenth century onwards, this led to a policy of pillarisation, causing and facilitating a politico-denominational segregation of society. Each segment or pillar – Protestant, Roman Catholic, Social Democratic – could clearly be differentiated by means of their own media, political parties, leisure clubs, schools, healthcare providers and funerary services. The institutional segregation emancipated the various groups and also reduced personal contacts between the members of different pillars to a minimum. The liberals who fundamentally opposed the segmentation ironically ended up in a (rather small) pillar of their own. As the government accommodated the pillarised system, they also (probably unintentionally) helped to emancipate the working and lower middle classes from elite control.

The particular experience of the Second World War – the Dutch stayed neutral during the First World War, and the last ‘war’ they were involved with was the so-called Ten Day’s Campaign against Belgium in 1831 – instigated a desire to renew the political system and break down the segmentation. The process of ‘depillarisation’ began, and turned on steam from the 1960s onwards. Today remnants of the former policy are still visible, particularly in the media and in education. Public television, for example, is organised through pillarised broadcasting companies, as are several newspapers. Also, the historic patchwork of political parties and the consequent multiple party coalition governments has become common practice in the Netherlands. The desire to break down the segmentation has also grounded the Dutch socio-economic model of consensus decision-making, the so-called poldermodel, common good throughout the 1980s and 1990s.

1.3. MIGRATION AND DIVERSITY

In the second half of the twentieth century, the Netherlands further diversified. As the pillars crumbled, church membership dropped and individualisation processes accelerated. Moreover, a variety of religious and cultural groups arrived in the Netherlands, for example, through guest worker programmes or after the dismantling of colonial administrative services, for example, in Indonesia. These migrants brought with them a variety of customs and practices, including funeral repertoires that had to be reinvented in view of this new context, where they found themselves in a minority position.

Migration has always been part of Dutch history.1 Immigration spiked from the sixteenth century onwards, when tens of thousands of Protestants (from the Southern Netherlands and elsewhere in Europe) found a safe haven in the Northern Netherlands. Portuguese and Spanish Jews, fleeing the Spanish inquisition, were followed by German- or Yiddish-speaking Jews and French Huguenots in the seventeenth century. These were highly prosperous times in the Netherlands, making it attractive for large numbers of labour migrants from (what is now) Germany and Eastern Europe. Emigration was rather low. Certain Protestant groups, like the Mennonites, were in open conflict with the rather strict Calvinists and searched for a new home elsewhere. Sailors and soldiers were recruited to support the trade activities of the Dutch West India Company, a company that was instrumental in the short-lived Dutch colonisation of the Americas, and the Dutch East India Company that developed commercial and industrial activities in South East Asia.

Whereas there was little immigration in the nineteenth century, numbers gradually increased in the twentieth century as people became richer, travel became faster and more affordable, and international trade expanded. Between 1946 and 1963 about 400,000 people arrived from the Dutch East Indies, as they were unable to stay after the proclamation of Indonesian Independence in 1945 and its recognition by the Dutch government and the UN in 1949.2 At about the same time, about half a million people left the Netherlands to find a better (and safer) future in Canada and Australia, but also in New Zealand, South Africa, Brazil and the United States. Between 1960 and 1974, 150,000 ‘guest workers’, mainly from Turkey and Morocco, were recruited for industrial labour to support the rapidly growing Dutch economy.3 Due to family reunification their number continued to increase after 1974.

In anticipation of the independence of Surinam in 1975, many – mainly Hindustani and Javanese – migrated to the Netherlands. Inhabitants of Suriname and the Dutch Antilles were granted Dutch nationality in 1954 and were free to relocate within the Dutch Kingdom. Also after independence large numbers of Surinamese (predominantly Afro-Surinamese) continued to immigrate to attend higher education and to reunite with family. Today, Suriname has a population of 556,485 and 351,681 people of Suriname descent are living in the Netherlands.4

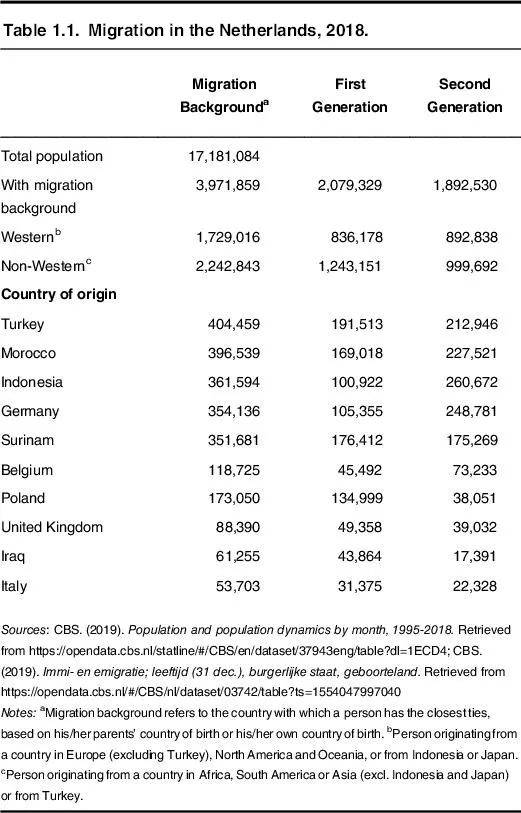

From the 1990s onwards, war and famine caused a rising number of refugees to settle in the Netherlands, for example, from (former) Yugoslavia, Congo, Sri Lanka, Afghanistan, Iraq, Somalia and more recently from Syria.5 They do share migration motives and experiences but are of diverse national, cultural and religious backgrounds. In 2018, 23% of the Dutch population has a so-called migration background (see Table 1.1).6 The migration balance – the number of people who settled in the Netherlands minus residents who left the Netherlands to settle elsewhere – was 80,665 in 2017.

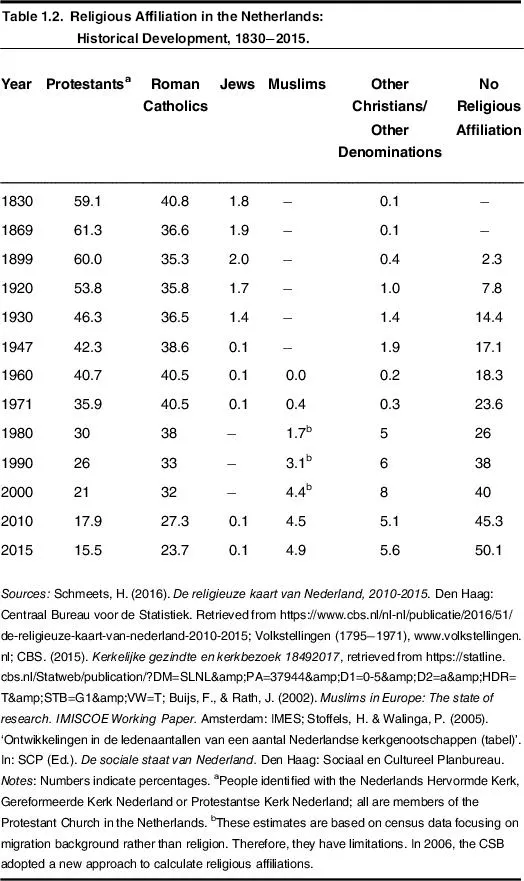

1.4. RELIGION IN NUMBERS

In 2015, Statistics Netherlands (CBS) found that 50.1% of the adult population declared to be not religiously affiliated. Christians comprised 43.8% of the total population and were divided between Catholics with 23.7% and the members of the Protestant Church of the Netherlands with 15.5%, members of other Christian denominations were 4.6%. Muslims comprised 4.9% of the total population, Hindus 0.6%, Buddhists 0.4% and Jews 0.1% (see Table 1.2).7

As Dutch society has become super-diverse, a wide variety of ideas and practices have emerged both in- and outside religious and ideological movements. These include ‘new’ perspectives on dying, death and grief. People actively look for funerary practices that suit the current time and circumstances.

NOTES

1. For detailed information on five centuries of migration to and from the Netherlands: Obdeijn, H., & Schrover, M. (2008). Komen en gaan. Immigratie en emigratie in Nederland vanaf 1550. Amsterdam: Uitgeverij Bert Bakker.

2. Obdeijn and Schrover (2008), pp. 229–248.

3. Obdeijn and Schrover (2008), p. 284.

4. Obdeijn and Schrover (2008), p. 255; CBS. (2018). Retrieved from https://statline.cbs.nl/Statweb/publication/?DM=SLNL&PA=71090NED&D1=0&D2=0&D3=0&D4=7&D5=1-2&D6=96%2c108&VW=T

5. Obdeijn and Schrover (2008), p. 328.

6. Retrieved from https://www.cbs.nl/en-gb/background/2018/47/population. Accessed on March 30, 2019; the CBS defines a person with a migration background as a ‘person of whom at least one parent was born abroad. A distinction is made between persons born abroad (first-generation) and persons born in the Netherlands (second-generation)’. See https://www.cbs.nl/en-gb/our-services/methods/definitions?tab=p#id=person-with-a-migration-background. Accessed on March 30, 2019.

7. Schmeets, H. (2016). De religieuze kaart van Nederland, 2010-2015. Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek. Retrieved from https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/publicatie/2016/51/de-religieuze-kaart-van-nederland-2010-2015.

CHAPTER 2

HISTORY

2.1. THE SIXTEENTH AND SEVENTEENTH CENTURIES

The Roman Catholic Church and its priests have played a dominant role in people’s dealings with death and dying in the Netherlands. Over time, the Church had incorporated pre-Christian notions of death into its liturgy.1 These notions and the associated practices had appeared to be rather persistent and difficult to change. From the fourteenth century onwards, the position of the Church itself, and especially its authoritarianism, became increasingly questioned.2 The sixteenth and seventeenth century were tumultuous times in Europe with widespread wars fought over both political and religious issues. The Netherlands, led by Calvinists, freed themselves from Spanish (and Roman Catholic) rule. Several provinces created a confederacy in 1581 and in 1648, after the Dutch Revolt or the Eighty Years’ War, the Dutch republic was recognised. The Dutch Reformed Church – de Nederlandse Hervormde Kerk – was founded in 1571.3 Theologically it was shaped not only by John Calvin, but also by other major Protestant Reformers. Further theological developments and controversies during its history, including Arminianism, the Nadere Reformatie (1600–1750) and a number of splits in the nineteenth century, such as the Doleantie led by Abraham Kuyper, would greatly diversify Dutch Calvinism.

When the independence of the Netherlands was recognised in 1648, the country did not only contain the seven Protestant provinces of the Dutch Republic. It also included the Generality Lands (Generaliteitslanden), roughly the current southern provinces of North Brabant and Limburg, which remained Catholic. The country could practically be divided in a Protestant North and a Roman Catholic South, although significant Catholic enclaves have always remained in the north. The Protestants rejected Catholicism and the native Catholics, and treated them in a harsh manner. Simultaneously, however, they were tolerant towards the Jews and they took in religious dissenters from elsewhere, including other Protestants.

The Protestant North was not unified. The Dutch Reformation had spread through multiple popular movements, rather than via one reigning power, and multiple churches existed. Although never formally adopted as the state religion, the Dutch Reformed Church did enjoy the status of ‘public’ or ‘privileged’ church. Until 1795 every public official had to be a communicant member, and the Church thus had close relations with the Dutch government.

Calvinists formally restrained funeral rites. The 1618–1619 Synod of Dort prohibited the tradition of sitting vigil at a deathbed (dodewake), a custom among both Jews and Catholics.4 The Synod also abolished the eulogies and the symbolic scoop of earth that relatives ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- 1. The Netherlands: An Introduction

- 2. History

- 3. Demographic and Legal Frameworks

- 4. The Funeral Directing Industry

- 5. Paying for Funerals

- 6. A Typical Funeral

- 7. Burial and Cemeteries

- 8. Cremation and Crematoria

- 9. Death and Remembrance in the Public Sphere

- Bibliography

- Index