eBook - ePub

Elites and People

Challenges to Democracy

- 280 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Elites and People

Challenges to Democracy

About this book

This volume contains an Open Access chapter.

Relationships between elites and democracy have always been strained. The very concept of elites - of 'chosen people' - stands in contradiction to democratic ideals of political equality. Simultaneously, they are necessary parts of democratic societies. In any large-scale society, democracy is unthinkable without large organizations, be they political bodies, bureaucracies, enterprises, or voluntary organizations. When power is concentrated at the summit of such organizations the incumbents of the top positions potentially constitute groups that often are termed elite groups.

The present volume of Comparative Social Research offers a broad set of comparative studies of elites, stretching from the Arab Spring in Tunisia and Egypt to women's political leadership in Brazil and Germany, via attainment of elite positions among minorities in France and the US.

The quality of democratic governance seems to be in decline in many parts of contemporary world. Nevertheless, political elections are still a main source of legitimacy, even when they are far from being free and fair. Developments in the Third Wave democracies established around 1990 both in Europe and in the rest of the world, are treated in several chapters. How do they fare two or three decades later? Another group of chapters sets the focus on elite recruitment and socialization, spelled out against class and gender. The volume concludes by highlighting various entanglements of elites with populism, concerning both underlying reasons for the recent populist expansion and the various images of elites in populist movements.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Elites and People by Fredrik Engelstad, Trygve Gulbrandsen, Marte Mangset, Mari Teigen, Fredrik Engelstad,Trygve Gulbrandsen,Marte Mangset,Mari Teigen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Democracy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

POLITICAL ELITES AND POPULATIONS

ELITE SURVIVAL AND THE ARAB SPRING: THE CASES OF TUNISIA AND EGYPT

ABSTRACT

The chapter compares the survival of old regime elites in Tunisia and Egypt after the 2011 uprisings and analyses its enabling factors. Although democracy progressed in Tunisia and collapsed in Egypt, the countries show similarities in the old elite’s ability to survive the Arab Spring. In both cases, the popular uprisings resulted in the type of elite circulation that John Higley and György Lengyel refer to as ‘quasi-replacement circulation’, which is sudden and coerced, but narrow and shallow. To account for this converging outcome, the chapter foregrounds the instability, economic decline and information uncertainty in the countries post-uprising and the navigating resources, which the old elites possessed. The roots of the quasi-replacement circulation are traced to the old elites’ privileged access to money, network, the media and, for Egypt, external support. Only parts of the structures of authority in a political regime are formal. The findings show the importance of evaluating regime change in a broader view than the formal institutional set-up. In Tunisia and Egypt, the informal structures of the anciens régimes survived – so did the old regime elites.

Keywords: Elite survival; regime change; revolution; Arab uprisings; Tunisia; Egypt

INTRODUCTION

The so-called Arab Spring triggered a euphoria of optimism, and in hindsight, it is obvious that many academics and observers grossly exaggerated the consequences of the uprisings that shook the Arab world in the spring of 2011. Mark Wasserman (1993, p. 71) believes this is a general trend, which applies to observers of revolutions. Often, the overthrow of a political system does not lead to deep transformations. The society and the economy go on as before. A revolution may seem like a catalyst for more long-term and subtle changes, but it is difficult to isolate the changes that the revolution led to and those that would have happened anyway. Also, the political consequences are often exaggerated. Did the revolution actually destroy the ruling elites associated with the old regime? To what extent did the new elite and the new regime change the way in which the country is governed? Have the people become more involved in the governance?

The fate of the old rulers is an overlooked topic in the history of revolutions, with a few exceptions: Albert Soboul (1989, p. 15) finds, in his study of the French Revolution 1789–1799 that aimed at destroying the formerly dominant class, that a ‘great many nobles lived through the revolution without coming to much harm and kept their property intact’. Wasserman (1993, p. 71), emphasising the persistence of the old elite in revolutionary Mexico 1910–1940, makes a similar observation:

the old elite … survived through a combination of the weakness of the revolutionary regime …, the growing compatibility of economic and political interests with the emerging new elite, and the considerable skills and sound strategies of its own members.

Likewise, parts of the elite survived the fall of Communism in Eastern Europe in the late 1980s/early 1990s, and re-established themselves in different important sectors. Dobrinka Kostova (2012, p. 166) notes with reference to post-Communism Bulgaria that

[…] part of the old elite has merged with the newly arising one and is managing to survive, transfer from one sphere to another and adopt to the new structures and institutions.

These studies indicate that a revolution is not necessarily a ‘clean break’ with the past, where the old elite is replaced by a new one. The old elite, or parts of this elite, might survive and thrive under the new regime. This is a useful lesson for all who strive to understand regime changes in the Middle East and North Africa in the wake of the Arab uprisings. A study of elite survival could help shed light on the nature of these changes, their depth and breadth and help us understand why the uprisings took the direction they took. All countries in the Arab world witnessed protests and unrest but to varying degrees and with very different consequences. The most troubled countries experienced three different outcomes: In Syria and Bahrain, the uprising was brutally suppressed by the sitting regime, not least thanks to military support from external powers. In Libya and Yemen, the uprisings led to total collapse, and no new elite has succeeded in consolidating power in the vacuum that arose after the fall of the old regime. In Tunisia and Egypt, revolutionary forces toppled the regimes of Ben Ali and Hosni Mubarak, respectively, and new regimes were eventually established. Accordingly, Egypt and Tunisia are the interesting cases for studying the survival of the anciens régimes’ elites.

It is important to emphasise that the Arab uprisings produced very different results in Tunisia and Egypt. With regard to democratic development, Tunisia has unarguably progressed while Egypt has moved in the opposite direction. Despite the huge differences, this chapter observes parallels concerning the elites’ ability to reproduce themselves. This makes it interesting to try to understand how. To study the degree of elite survival, we will map and compare the political elite before and after the Arab uprisings. It is not possible to present a comprehensive account within the chapter’s scope so we will focus on main features such as the relative strength of different elite groups and the composition of the ‘inner circle’. We shall compare the resources that the old elite had privileged access to, maintained and used to reactivate core elements of its pre-2011 power basis: money, networks, media and external support.

The chapter starts with a brief theoretical perspective that is useful for the further discussion of the rise and fall, and eventual re-emergence of elites in the cases of Tunisia and Egypt.

TYPES OF ELITE CIRCULATION

A key topic within elite research is ‘the rise and fall of elites’ (Gulbrandsen, 2017, p. 2). The history of the Middle East and North Africa is indeed a history about the constant rise and fall of elites – or dynasties, brilliantly described by the medieval Arab scholar Ibn Khaldun (2015/1377), who formulated an early version of the theory of circulation of elites. Vilfredo Pareto (1963/1916) was concerned with the same issue. He introduced the concept of ‘elite circulation’, which is a dialectical theory of an endless competition between elites with one elite group replacing another repeatedly over time.

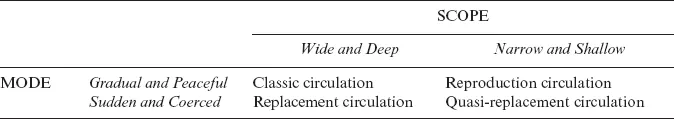

More recently, based on in-depth studies of the replacement of the old Communist elites by new elites in Eastern Europe in the late 1980s/early 1990s, John Higley and György Lengyel have made important contributions to our theoretical understanding of elite circulation. Higley and Lengyel (2000) argue that elite circulation might take different patterns, with regard to, first, its scope, which is the horizontal range of the positions affected and the vertical depth from which those entering elite positions come, and, second, its mode, which is the speed and manner in which it occurs (p. 4). The scope of circulation can be ‘wide and deep’ or ‘narrow and shallow’, while its mode can be ‘gradual and peaceful’ or ‘sudden and coerced’ (Higley & Lengyel, 2000, pp. 4–5).

On the basis of these dichotomies, Higley and Lengyel derive four types of elite circulation: the first is ‘classic circulation’, which is gradual and peaceful, wide and deep. This type of elite circulation is essential for elite renewal, and thus stable and effective governance. The second is ‘reproduction circulation’, which is gradual and peaceful but narrow and shallow. Through this type of circulation, the elite is preserving its control of central power positions. The third is ‘replacement circulation’, which is sudden and coerced, wide and deep. This type of wholesale replacement of an old kind of elite might be the outcome of coups or revolutions. The fourth, and final, is ‘quasi-replacement circulation’, which is sudden and coerced, but narrow and shallow (Table 1). This type of circulation is the result of a dramatic regime change in which parts of the elite associated with the old regime manage to survive (Higley & Lengyel, 2000, pp. 5–6).

Table 1. Patterns of Elite Circulation (Higley & Lengyel, 2000, p. 5).

THE CASE OF TUNISIA

Tunisia was the birthplace of the Arab Spring and is the country that has fared best in its aftermath. Ben Ali’s fall on 14 January 2011, after 23 years in power, set off a democratic transition. A constituent assembly elected on 23 October 2011 voted a new constitution on 26 January 2014, overcoming deep political divisions. It created a semi-presidential ruling system based on free elections, fundamental human rights and the separation of powers. The constitution guarantees personal and public freedoms and defines Tunisia as ‘a civil state based on citizenship, the will of the people, and the supremacy of law’ (Tunisia’s Constitution of 2014). Underneath this success lay an elite compromise between the Islamist al-Nahda party that had won the largest share of votes in the constituent assembly election (37 per cent, gaining 89 out of 217 seats) and the secular-leaning coalition Nidaa Tounes. Led by Tunisia’s president, Beji Caid Essebsi, Nidaa Tounes united opponents of al-Nahda from leftist revolutionary forces to members of the old elite.

Pre-Arab Spring

The pre-revolutionary elite had grown out of Tunisia’s two regimes after independence, Habib Bourguiba’s party-state (1956–1987) and Ben Ali’s police state (1987–2011). The first was built on a revolutionary break with the past that profoundly upset the pre-existing elite configurations. The second left more room for continuity because it presented itself as a reformist continuation of the first. Habib Bourguiba came to power as the leader of the Neo Destour party that broke with traditional elites and spearheaded the battle for independence. Its cadres were French-educated and shared a secular modernising vision that pitted it against the religious class (Henry, 2017). Geographically, the majority originated from the Eastern part of the Mediterranean coast. Contrary to strongmen in other Arab republics, such as Gamal Abdel Nasser in Egypt, Bourguiba was a civilian and distrusted the military. Like his contemporaries, on the other hand, he pursued a state-led, temporarily socialist, development model that left little room for private economic actors. The elite resided in the state bureaucracy, the ruling party apparatus and corporatist organisations such as the General Union of Tunisian Workers (UGTT) and the Tunisian Union of Industrialists, Merchants and Artisans (UTICA; Erdle, 2004, pp. 207–236).

Ben Ali staged a medical coup against Bourguiba in 1987, whose health problems raised concern in the elite about the president’s ability to lead – in a context of economic crisis. The new president was of military background and had built his networks and career in the secret police and the Ministry of Interior. Ben Ali had served as Director General of national security in two periods and was Interior Minister when assigned the premiership in 1987. He lacked a genuine power base in the ruling party. Ben Ali tried liberalisation of the regime as a tactic to win popular support, but retreated in 1989 when the Islamist movement showed its strength in national elections. He doubled down on networks in the security apparatus for the twin purpose of quelling criticism from Islamists and strengthening his position vis-à-vis the party elite, which dominated the state bureaucracy.

Ben Ali used his loyal cohorts in the security services to create a person-dominated regime w...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Elites and People: Challenges to Democracy

- Part I. Political Elites and Populations

- Part II. Elite Recruitment and Mobility

- Part III. Elites and Populism

- Index