![]()

— 1 —

The Occupation of Mallorca (Balearic Islands, Spain) in Late Antiquity: Tracing Change and Resilience

CATALINA MAS FLORIT AND MIGUEL ÁNGEL CAU ONTIVEROS

This chapter explores how the communities of the island of Mallorca adapted to a successive series of changes that occurred between the Roman period and the end of Antiquity. The available evidence shows a significant transformation in the cities and also in the countryside where the number of sites decreased in the third century A.D., and only a few large settlements remained occupied. This pattern changed abruptly at the end of the fifth or early sixth century with an increase in the number of rural settlements, including the reoccupation of old indigenous prehistoric sites and the construction of rural churches which are essential to understanding the process of Christianization of the countryside. Small villages or secondary agglomerations would also have played an important role in the configuration of the landscape.

The chapter briefly addresses the transformation of the city but is mainly focused on the transformation of the countryside. The phenomenon of the reoccupation of old indigenous sites, the fate of Roman rural sites, and the role of the early Christian churches are outlined to understand the transformation of this Mediterranean island between the fourth and the eighth centuries A.D.

Introduction

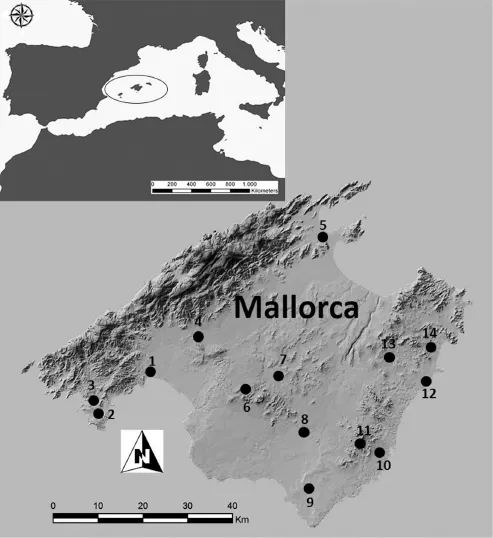

The Balearic Islands are the most remote archipelago of the Mediterranean sea. They lie off the coast of the Iberian Peninsula in a strategic position for navigation and trade routes in the western Mediterranean (Figure 1.1). Greek and Roman writers were fully aware of the archipelago and separated it into two groups of islands with substantial differences. On the one hand, Mallorca and Menorca formed the Baliarides (also called the Gymnēsiai by the Greeks), represented by the Talayotic culture. On the other hand, Ibiza and Formentera were considered the Pityussae, with a strong Phoenician-Punic character.

Figure 1.1. Location of the Balearic Islands in the western Mediterranean and map of Mallorca with the main sites cited in the text: 1. Palma; 2. Tumulus of Son Ferrer; 3. Rural Roman site of Sa Mesquida; 4. Basilica of Cas Frares; 5. Pollentia; 6. Puig de s’Escolà; 7. Talayotic village of Son Fornés; 8. Basilica of Son Fadrinet; 9. Es Fossar de Ses Salines; 10. Closos de Can Gaià; 11. Castell de Santueri; 12. Basilica of Sa Carrotja; 13. Basilica of Son Peretó; 14. Son Sard.

The society of the Baliarides experienced significant impacts from the Roman conquest in 123 B.C. Despite their society’s contacts with the Punic world and other influences, these islands were dominated by the Iron Age indigenous population at the time of the Roman military intervention. The Roman period brought with it the foundation of cities and the reorganization of the countryside. The islands were linked first to Hispania Citerior and later to Tarraconensis. The archipelago as a whole (i.e., the unified Balearides and Pityussae) did not become an independent province until the end of the fourth century. In A.D. 455, the Vandals conquered the islands and in A.D. 534 they fell into Byzantine hands. This latter dominance lasted, at least in theory, until the Islamic conquest of Isam-al-Jalawni in A.D. 902–903. The old Roman structures, transformed during Late Antiquity, probably vanished forever under the strong cultural influence of Islam.

Interest in the transformation of these islands in the period between the Roman military intervention and the Arab conquest of the tenth century is relatively recent. Written sources are in general very scarce, and much of the information has to come from archaeology. This chapter offers some insights into the occupation of Mallorca during Late Antiquity, trying to understand the changes witnessed and the strategies that the local population adopted in a period (or, better, subsequent periods) of crisis and upheaval.

The Transformation of the Cities

The Roman conquest in 123 B.C., led by Q. Cecilius Metellus, resulted in the foundation of two cities in Mallorca: Palma and Pollentia (Figure 1.1). Regarding the city of Palma, now under the current city of Palma, there are little data available to provide an outline of its transformation in Late Antiquity (Cau 2012). However, two ceramic deposits dated to the Vandal and the Byzantine periods show the occupation of the city (Cau et al. 2014). The evidence so far suggests that population at the time prior to the Muslim conquest of the city was both small and in decline (Gutiérrez 1987: 206). It seems that the Muslim city of Madîna Mayûrqa was placed over a former urban centre still in operation (Riera i Frau 1993: 27–29). Most of the available data for the study of the transformation of Mallorcan cities, therefore, comes from Pollentia.

Concerning Pollentia, archaeological data show continuous use of the urban space, albeit with various re-organizations, since the foundation levels dated around 70–60 B.C. The third century A.D. was a moment of serious disruption in the city. A major reorganization occurred either at the very end of the second century or the beginning of the third. The excavations in the forum have demonstrated a complete transformation of the socalled Insula I of tabernae to the West of the forum square. Many rooms were restructured, with walls rebuilt, changing the overall dimensions and building small buttresses in some of them. The streets were also profoundly modified, and many of the spaces between the columns of the porticoed streets were closed off (Cau 2012). At the end of the third century, a massive fire destroyed various parts of the city, as clearly attested in Insula I. This destruction has been dated with precision to around A.D. 270–280 (Arribas et al. 1973; Arribas and Tarradell 1987: 133; Equip d’Excavacions de Pollentia 1994: 142; Orfila 2000). The third century was, therefore, a time of strong disruption to the city. The construction of a wall in the so-called residential quarter of Sa Portella was probably done in the same century, as a response to this moment of upheaval (Figure 1.2) (Orfila et al. 2000; Riera i Rullan et al. 1999). Nevertheless, there is no doubt that inhabitation continued in the city after the third century. By the fourth and fifth centuries, there is apparently little building activity, but there exist some industrial structures in the forum of Pollentia built over the debris of the late third-century fire. Some of the tabernae seem to be re-occupied by squatters (Orfila et al. 1999: 112–113; Orfila 2000: 154). Public spaces were also occupied: in the fifth century, for example, a room was attached to the façade of the Macellum, invading the portico area on the east side of the forum. By this time the city was deeply transformed, and certain buildings, such as the Macellum, were now abandoned. Some tabernae and the forum square have provided materials that denote later reuse of these spaces.

Figure 1.2. View of the so-called residential quarter of Sa Portella in the Roman and Late Antique city of Pollentia (Alcúdia).

The most significant structure in Late Antiquity, however, was the fortification located to the north of the forum area. Its construction involved the use of spolia from other buildings, with many elements being reused in the inner filling of the wall. This defensive structure closed off at least some of the old forum that was partially in ruins and occupied parts of public spaces, such as the north street (Figure 1.3). A dating in the Byzantine period has been suggested for this (Orfila et al. 1999: 113–116; 2000). The fortification indicates the enclosure of a protected perimeter, such as a citadel, in the very heart of the city, coinciding with the location of the forum and reusing the wall of the Capitolium, Insula I and the Macellum. Outside this citadel, there was continued inhabitation of the city, and Sa Portella shows clear signs of occupation dating to the Late Roman, Vandal, and Byzantine periods, with significant material culture (e.g., Arribas et al. 1973; Gumà et al. 1997).

Figure 1.3. The Late Antique fortification of the forum of Pollentia occupying the porticoed street to the north of the forum with a wall dated to the end of the second century or beginning of the third century closing off the intercolumniation.

The Christianization of the topography of the city is virtually unknown. Some early discoveries were claimed to be related to the presence of Christian buildings in the city. For instance, in a necropolis area within the suburbia known as Can Fanals, a large building in a very poor state of preservation was interpreted as a possible basilica (Llabrés and Isasi 1934). Moreover, further north, in the so-called area of Santa Anna de Can Costa, some graves and the early Christian inscription of Arguta were tentatively linked to the presence of another Christian building. These were already inside the urban layout, suggesting the transformation of the city.

Over the ruins of the old forum, a large necropolis has been radiocarbondated to the Muslim period. The most interesting aspect is that the inhumations were still in supine position and not in a lateral position, as would have been the norm for Islamic populations; this might be a sign of non-Muslim communities being buried between the tenth and the twelfth centuries on top of the ruins of the Roman city (Cau et al. 2017). The only structure respected by the graves we have excavated in the forum is the Capitolium, so it seems that this building was still partially standing or at least respected, although parts would surely have been dismantled by then. Some authors have proposed the possible transformation of the Capitolium as a place of Christian worship (e.g., Arribas and Tarradell 1987).

The Transformation of the Rural Areas

The initial interest in the Roman rural occupation provided the first systematic data to understand the transformation of rural landscapes in Mallorca (Orfila 1988). Recent fieldwalking surveys of several areas across the island have contributed to new information that allows a first interpretation of the changes that occurred in the countryside from the Early Roman period to the Early Middle Ages (Mas Florit and Cau 2013). The general pattern of settlement on the island seems to be defined by the continuity of prehistoric sites and the creation of newly-founded Roman settlements, apparently rather few in number (Cardell et al. 1990). Some of these possible villae, hamlets, farms or farmsteads have been located by fieldwalking, although excavation has occurred on very few of them. Therefore, the phenomenon of the implantation of the villa system and its evolution in the countryside, as well as the role of the indigenous settlements in this wider framework, is still not sufficiently studied. As we will see later, the few data available suggest that these villae were implanted around the Augustan era or slightly earlier (Mas Florit et al. 2015). The landscape was clearly divided and distributed, as traces of centuriation have been identified (e.g., Cardell and Orfila 1991–1992), something that indeed facilitated the administration of property and tax collection.

Studies undertaken on the eastern side of the island show the abandonment or decay of many medium- and small-size rural sites during the late second and the third century A.D. Only a few sites, always with large dimensions and located in areas of fertile plains, have been documented. This decrease in the number of sites, and the fact that only large settlements seem to survive, has been interpreted as a sign of the concentration of property (Mas Florit and Cau 2013). Such a development has also been observed in other areas of the western Mediterranean, where medium and small properties were concentrated to form large landho...