![]()

The Archaeology

![]()

CHAPTER 3

Chalk and the chalklands of southern England

Andrew Meirion Jones and Marta Díaz-Guardamino

The chalklands of southern England have long fascinated antiquarians and prehistorians (Lawson 2007). Most of the celebrated monuments of the British Neolithic are situated on the chalk: the enclosures of Maiden Castle, Hambledon Hill and Windmill Hill; the Dorset cursus; Silbury Hill; the henge complexes at Avebury and Stonehenge. The chalklands of southern England are justifiably important.

Yet remarkably little attention has been paid to the substance of chalk itself. How is it worked and used? Why are objects carved from chalk, and what (if anything) do they represent? How do objects of chalk relate to the other carved and decorated materials found in the region?

The geology of chalk differs across the region. Chalk also differs stratigraphically: the upper, middle and lower chalk is substantially different. Upper chalk is a much softer and soapier substance, while the middle and lower chalks are nodular and blocky. Chalk is an amazingly messy material. A day spent digging on chalk, or looking at chalk artefacts in museum collections, leaves clothes covered in a greasy and mucky spread of chalk; hair often covered in fine chalky particles. Chalk is a malleable substance. It can be hard and blocky. It can be greasy. It can be fine and crumbly. Chalk can be puddled and – as a slurry – used as a concrete like building and rendering material, in Dorset this traditional building material is known as ‘cob’. One of the delights of this project has been coming to terms with chalk, whilst also gaining an understanding of how Neolithic populations came to terms with chalk through working this remarkable substance. Neolithic craftspeople and contemporary researchers alike were interested in what chalk is capable of.

The region covered in this chapter is extensive. Our predominant interests are the chalk-rich regions of southern England extending as far as the south coast, Wiltshire, Dorset, and Sussex. We also examine activities in the Breckland regions of East Anglia, notably Norfolk. Our analysis also covers activities in the Somerset levels, and extends as far west as the granites, schists, and limestones of Cornwall. Finally, our region extends as far north as the River Thames. The region takes in some of the classic areas of British prehistory: Wessex, the Thames valley, and East Anglia. It also has the advantage of covering a large extent of the Neolithic period (Fig. 3.1).

FIGURE 3.1 Map of southern England and East Anglia with sites discussed marked on the map. 1: Harrow Hill 2: Cissbury 3: Whitehawk 4: the Trundle 5: Lavant 6: Thickthorn Down 7: Windmill Hill 8: Monkton Up Wimborne, Tarrant Monkton and Wyke Down 9: Truro 10: Garboldisham 11: North Marden 12: Maiden Castle 13: Maumbury Rings, Flagstones and Mount Pleasant 14: Grimes Graves. The river Thames denotes a series of find spots in the London region, the Somerset Levels denotes the site of the prehistoric trackways mentioned in the text, while Salisbury Plain denotes the site of the Amesbury and Butterfield plaques and Woodhenge.

(IMAGE: HANNAH SACKETT)

Many of the artefacts studied in this project have little or no context; one of the aims of the project is to reassess the contextual and chronological framework for decorated artefacts. This region provides some of the best contextual detail for Britain and Ireland as a whole. It is important that this is given due attention. To this aim, the chapter is organised chronologically.

Our aim in this section of the project is not to examine every decorated artefact, but to focus on large assemblages of artefacts (e.g. the assemblages from Windmill Hill, Maumbury Rings and Mount Pleasant, the group of antler mace heads from the Thames), or to examine important decorated artefacts (e.g. the Garboldisham mace head, the Monkton Up Wimborne chalk block).

Working chalk from c. 4050–3600 BC

The recent statistical analysis of radiocarbon dates from the southern British Neolithic (Whittle et al. 2011) identifies some of the earliest sites in the British Neolithic: these are the flint mines of Sussex. Based on dates from flint mines, including Harrow Hill, Cissbury, Blackpatch and Church Hill, Alasdair Whittle and colleagues conclude that it is 99% probable that there was a Neolithic presence in Sussex before the construction of causewayed enclosures, and that this activity probably began in the 40th century BC (Whittle et al. 2011, 257; Baczkowski 2014). This project analysed mark making activities from the flint mines of Harrow Hill and Cissbury.

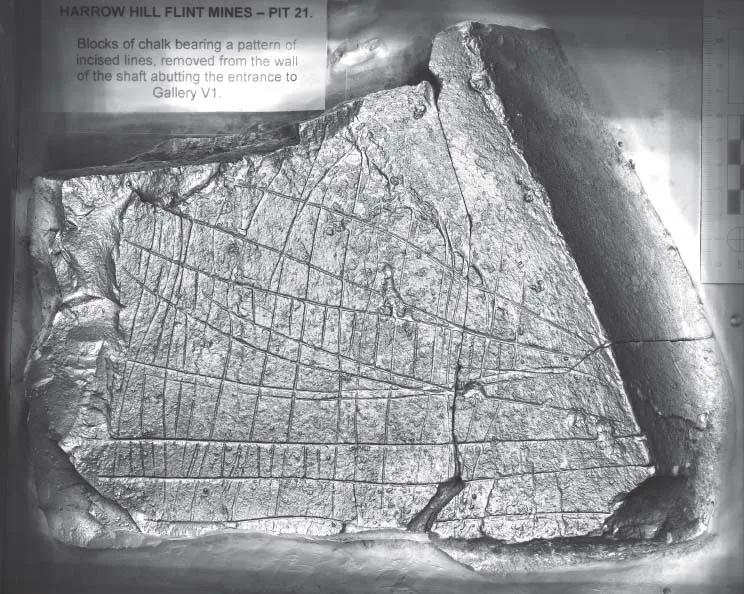

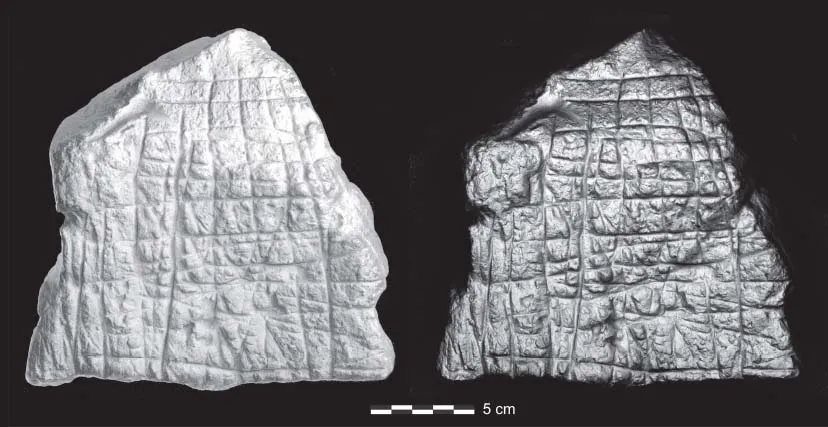

Healy and colleagues (Healy et al. 2011) indicate that flint was worked at Harrow Hill between 4250–3705 cal. BC (95% probability), probably 4020–3785 cal. BC (68% probability), while working at the mine ended 3750–3395 cal. BC (95% probability), probably 3695–3580 cal. BC (68% probability). Artefacts from Harrow Hill (Curwen and Curwen 1926; Holleyman 1937; McNabb et al. 1996) are sparse, and mainly consist of several lumps of worked chalk. Far more interesting are the marks carved on the wall of pit 21, gallery VI. The panel of marks from this context, preserved in Littlehampton Museum, were recorded using RTI. They are a cross cutting grid design (Fig. 3.2), and clearly indicate at least two phases of working. The lower design is made up of a series of parallel linear horizontal lines with short vertical infill. Overlaying, and cross-cutting this design are a series of more haphazard vertical lines.

FIGURE 3.2 RTI of markings from Harrow Hill, shaft 21.

(IMAGE: MARTA DíAZ-GUARDAMINO, © LITTLEHAMPTON MUSEUM)

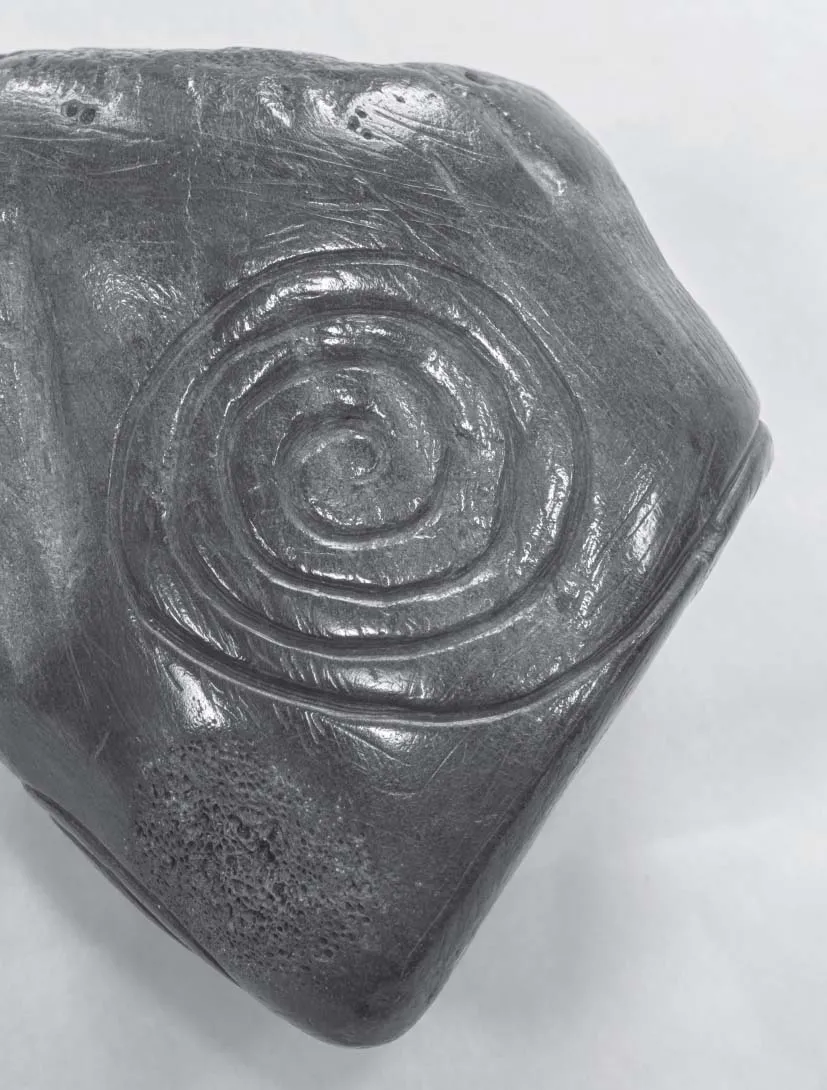

Healy and colleagues (Healy et al. 2011) indicate that flint was worked at Cissbury between 4600–3705 cal. BC (95% probability), probably 4120–3795 cal. BC (68% probability), and working at the mine ended 3595–2635 cal. BC (95% probability), probably 3495–3075 cal. BC (68% probability). The artefacts from Cissbury (Lane Fox 1876) are held by two museums: Worthing Museum and the Ashmolean, Oxford. We analysed the collection from Worthing, but the Ashmolean collection was being worked on by another project and was unavailable for study. The chalk artefacts from Cissbury are small in number and include two blocks of chalk, both evidently cut from a deep stratigraphy in the chalk because of their large and blocky character; both blocks have cups or hollows carved in their upper surfaces. Although we were unable to access the other material from Cissbury the publication of some of this material (Teather 2015) clearly indicates evidence for pick marking on small portable chalk blocks, and cross-cutting linear marks made either by antler picks or flint (e.g. Teather 2015, Fig. 5). Analysis of these pieces suggests the possibility of ochre pigment overlaying some of these designs, though this needs to be confirmed by further analysis. We regard the representational interpretation of some of these designs (e.g. Teather 2015, Fig. 2) as debateable, given the sparseness of representational imagery in the British Neolithic (see Chapter 11 for further discussion of representation). Like the material from Harrow Hill, it seems feasible from the published information that we might also observe evidence for multiple phases of mark making at Cissbury, though it is difficult to be certain about this purely based on published sources.

We should also note the etched stone derived from a pit at New Barn Down, Worthing, Sussex. The pit, originally excavated by E. C. Curwen in 1933, has been recently re-analysed by Jon Baczkowski (Baczkowski Forthcoming). The pit is dated to the 40th–38th centuries cal. BC and contains a stone, originally interpreted as a grain rubber. The lower surface of the stone has a series of fine non-random linear marks, which might be regarded as deliberate mark making. This stone is curious, though it is difficult to be absolutely certain that these marks are deliberate. We discuss it here mainly due to its early date, and its comparability with the mark making in flint mines.

A series of chalk artefacts were also analysed from causewayed enclosures in Sussex including those at Whitehawk and the Trundle. We now have much more precise dates for each of these sites.

Whitehawk

The four circuits of the Whitehawk enclosure (Curwen 1934; 1936; Ross Williamson 1930) begin life between the middle of the 37th century and the end of the 36th century BC, with a 95% probability of primary use for 75–260 years (Whittle et al. 2011, 226). The construction dates of the inner ditch, ditch I, are estimated at 3635–3560 cal. BC (95% probability), probably 3635–3580 cal. BC (68% probability), with ditch II dating from 3675–3630 cal. BC (72% probability), probably 3665–3635 cal. BC (67% probability). It is probable that ditch II is earlier than ditch I (Whittle et al. 2011, 221–3).

Dates for later activity at the site include those from ditches III and IV: ditch III is estimated at 3660–3560 cal. BC (95% probability), probably in 3650–3600 cal. BC (68% probability). Ditch IV is estimated at 3650–3505 cal. BC (95% probability) or 3600–3530 cal. BC (50% probability); in both ditches III and IV these dates almost certainly relate to the recut of the ditches (Whittle et al. 2011, 225). A total of 27 chalk artefacts were recorded by the project. The artefacts include 9 chalk blocks with weights over 1200 g that have perforations and occasional incisions; 4 smaller blocks with irregular incisions; 2 incised plaques; 4 cups or receptacles, at least one highly decorated; and 8 perforated chalk lumps.

Analysis of the precise dates of these artefacts is impeded by a lack of detailed stratigraphic information in the published reports. However, some of the artefacts can be more precisely located. Some of the large chalk blocks and lumps, some with perforations, were associated with skeleton II in the terminus of ditch III (Curwen 1934, 108); these blocks (Brighton Museum Accession no. R3688/174) were part of the grave architecture; the skeleton was that of a female aged between 20–25 years (Tildesley 1934, 124). In addition, two perforated pieces of chalk (Brighton Museum Accession no. R3688/115) – described as ‘weights’ by Curwen (1934, 108) – underlay the skeleton. As the skeleton and its grave were located in the upper fill of ditch III these deposits must date from the later date noted above. A further artefact that can be more precisely located is the ‘chequerboard’ incised chalk plaque (Brighton Museum Accession no. R4100/132), which is from the third ditch (A-D III) from level 4, described as:

…rapid chalk silt, containing near the top several Neolithic shards and bones of animals. (Curwen 1936, 65)

It is presumed that this is just below the primary occupation deposits (layer 3), and therefore relates to the early dates noted above. A triangular piece of chalk with an hourglass perforation (Brighton Museum Accession no. R4100/131) also came from the same deposit. A chalk cup (Brighton Museum Accession no. R4100/130) with hollows on both its upper and lower surfaces is from A-D I 2, or the upper layers of the inner ditch (Curwen 1936, 62). This therefore postdates the early dates noted above.

Taking the Whitehawk chalk artefacts as a whole we have a series of objects, such as the large and small blocks, that attest to an expedient or even experimental engagement with chalk; by partially perforating or drilling into it, by incising into its surface. More deliberate and repetitive practices of working chalk occurred from early in the life of the site, as we see with the ‘chequerboard’ plaque, in which a series of incisions cross-cut each other. Equally as interesting as the ‘chequerboard’ plaque is the other plaque from the site (R4100/133), which has haphazard incisions carved into its upper and lower surfaces, and indeed on the sides of the plaque (Fig. 3.3). Both plaques speak of repetitive working: the ‘chequerboard’ plaque appears superficially systematic but features cross-cutting incised marks, whereas R4100/133 has incised marks that cross-cut on its upper and lower surfaces. The cups are also intriguing as at least one has been hollowed out on two surfaces, and a further more ‘vase-shaped’ vessel has been more intensely decorated by incision. Incision on these artefacts need not only relate to manufacture, but may also be an intentional feature of their design. On the basis of the dates from the sites, it is clear that similar practices of working chalk continue through the life of the site.

FIGURE 3.3 RTI of markings on chalk plaque from Whitehawk causewayed enclosure, Sussex.

(IMAGE: MARTA DíAZ-GUARDAMINO, COURTESY OF ROYAL PAVILION & MUSEUMS, BRIGHTON & HOVE)

The Trundle

The Trundle enclosure, Sussex (Curwen 1929) consists of three circuits of ditches. Dates from the site are equivocal, ‘since there is no evidence that any of the samples [dated] were freshly deposited’ (Whittle et al. 2011, 238). Because of the difficulty in attributing the dated samples to primary activity, Alasdair Whittle and colleagues provide two models (Whittle et al. 2011, 239), the more conservative of which is taken here. They simply state that the inner ditch of the site may date to after 3900–3370 cal. BC (95% confidence), and probably after 3710–3525 cal. BC (68% confidence), while ditch 2 was probably dug after 3650–3520 cal. BC (95% probability), and probably after 3640–3530 cal. BC (68% confidence). The spiral (outer) ditch dates to after 3940–3370 cal. BC (95% confidence), probably 3710–3530 cal. BC (68% confidence).

The collection of worked chalk from the Trundle i...