![]()

1

JAPANESE AND KOREAN LABOR

MARKETS AND SOCIAL PROTECTIONS

IN COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE

During the 1990s and 2000s, Japan and Korea promoted labor market reforms that differed substantially from those of other advanced industrialized countries, and despite being a somewhat similar pair of market economies in many important ways, they approached labor market reform with two different strategies and with two dissimilar sets of consequences. This chapter elaborates three key institutional aspects of the labor market and social protection—employment protection, industrial relations and wage bargaining, and social protection programs—in Japan and Korea in comparison with those in other advanced industrialized countries. In particular, it shows the ways in which a set of labor market institutions and social protection programs have adapted to new challenges in their national political economies and how they have interacted with one another in the process of labor market reform.1

The first section illustrates the similarities and differences in employment protection regimes, the diverging patterns of labor market reform, and the sharp rise in inequality and dualism in the Japanese and Korean labor markets. The second section examines decentralized industrial relations, wage-bargaining institutions, and the features of the wage structure in the two countries. The third section describes various social protection programs associated with labor market reform. A concluding section summarizes cross-national variations in the pattern of labor market reform and convergence in the rise in inequality and dualism, but with different degrees of inequality and dualism along the lines of employment status (e.g., regular workers versus non-regular workers) and firm size (e.g., large firms versus SMEs) in Japan and Korea.

Employment Protection

Employment Protection Regimes in Comparative Perspective

The labor market is located at the intersection of several key institutional domains of the national political economy. A wide array of formal and informal labor rules and regulations shape firms’ strategies for production and investment. For workers, the labor market offers jobs and social protections to support themselves and their family members. Meanwhile, it has been a critical policy issue for governments to identify a viable labor model that would satisfy the dual tasks of achieving sustainable growth and achieving equitable distribution. Thus, the labor market has always been the locus of political contestation between business, labor, and government over the rules and regulations governing employment contracts, working conditions and hours, and social protections that affect employers’ production and investment strategies and workers’ quality of life.

In the face of economic crisis, advanced industrialized countries have undertaken labor market reform, from the 1980s and onward, as a primary policy tool for rapid economic turnaround, job creation, and sustainable economic growth (Iversen 2005; Levy 2005; Palier 2005; Palier and Thelen 2010). Labor market reform is a multifaceted concept associated with a broad range of changing rules and regulations in the labor market, encompassing individual labor rights (e.g., employment contracts, working conditions, and work hours), collective labor rights (e.g., workers’ basic rights to organize, strike, and bargain collectively), and social protection programs (e.g., active and passive labor market programs and social welfare benefits) (Caraway 2009; Etchemendy 2004; Levy 1999 and 2005; Miura 2002b; Murillo and Schrank 2005; Palier and Thelen 2010). Among various reform agendas, policy makers in most advanced industrialized countries prioritized lowering the level of employment protection for workers, such as easing hiring and firing practices, deregulating working conditions, and promoting the flexible allocation of work hours. Especially in many continental European countries, a high level of employment protection was regarded as a huge financial burden on labor adjustments for employers during economic downturns and was blamed as the main culprit behind economic malaise (OECD 1994 and 1999a; Siebert 1997).2 By advancing a series of labor market reforms, policy makers intended to respond to the mounting pressures for change in their national political economies.

Since employment protection is considered one of the most crucial institutional pillars of the labor market, several strands of the existing literature attempt to explain cross-national variations in the level of employment protection. First, the varieties of capitalism (VOC) approach points out that different institutional arrangements of capitalism lead to the two distinctive types of market economies: coordinated market economies (CMEs) (e.g., countries in East Asia, continental Europe, and Scandinavia) and liberal market economies (LMEs) (e.g., the United Kingdom and the United States) (Hall and Soskice 2001). It explains that CMEs are centered on nonmarket-based strategic coordination among key economic actors over the long term, whereas LMEs are based on the principle of a laissez-faire economy. In the realm of the labor market and social protections, the VOC approach posits that CMEs tend to develop strong employment protection regimes with generous social protections anchored in long-term economic transactions, which facilitates cooperation between employers and skilled workers, whereas LMEs are more likely to institutionalize weak employment protection regimes with meager social welfare programs because of the nature of short-term economic transactions based on the market principle (Estévez-Abe, Iversen, and Soskice 2001).

Second, the power resource theory, focusing on the strength of labor as the determining factor in policy outcomes, claims that the power of organized labor and a pro-labor left government account for strong employment protection and generous social welfare benefits (e.g., Scandinavian countries). Meanwhile, it points out that weak employment protection and meager social welfare programs in countries like the United Kingdom and the United States can be attributed to weak labor and the lack of strong left political parties (Bradley et al. 2003; Huber and Stephens 2001).

Last, building upon the legal theory approach, other scholars argue that the origins of the legal system explain the variations in the regulation of labor, regulation that ranges from employment laws and collective relations law to social security laws (Botero et al. 2004). This strand of research claims that countries whose judicial systems originate from the common law system (e.g., the United Kingdom and the United States) are more likely to develop less-protective labor regulations and to bring forth better labor market outcomes (such as high labor force participation rates and low unemployment rates) than those based on legal systems with other origins (e.g., the socialist, French, and Scandinavian laws).

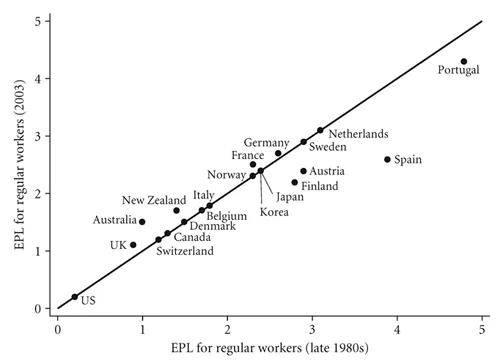

Empirically speaking, most countries remain grouped in the same categories across the different theoretical frameworks. As a few exceptions to note, while the VOC approach predicts a high level of employment protection in CMEs, Denmark and Switzerland (as exemplary cases of CMEs) have developed much lower levels of employment protection than other CMEs (see figure 1.1). Contrary to the theoretical predictions of the power resource theory, Japan and Korea, two primary examples of weak labor—labor there is even weaker than in the United Kingdom and the United States, measured by union organization rates—have developed a medium-high level of employment protection for regular workers, a level much higher than that of the United Kingdom or the United States.

FIGURE 1.1 Employment protection regimes for regular workers

Source: OECD (2004, 117).

Note: EPL refers to the scores of employment protection legislation measured by OECD; for Korea and New Zealand, the scores of the late 1980s are replaced by those of the late 1990s because of the availability of data.

From the theoretical perspective, all these approaches take a rather static view of the labor market since they focus more on the level of employment protection itself at a given moment as opposed to changes in the level of employment protection.3 For instance, the legal theory approach cannot account for variation in the politics of labor market reform within countries with legal systems of the same origins, unless countries reform the institutional foundations of the judicial system. While the VOC approach acknowledges the possibility of institutional changes derived from the concept of institutional complementarities, it emphasizes instead an institutional equilibrium in market economies, as opposed to the mechanism of institutional change. The power resource theory may account for radical labor market reform in countries with weak labor and gradual policy changes in countries with strong labor. Nevertheless, it falls short of explaining why countries like Japan have not advanced sweeping labor market reform, despite the political and organizational weakness of labor. It is crucial to understand the origins of the different levels of employment protection, but this study emphasizes the content and direction of changes in employment protection in response to global and national economic crises. Thus, this study analyzes how these labor market institutions have changed, as opposed to how they were originally established.

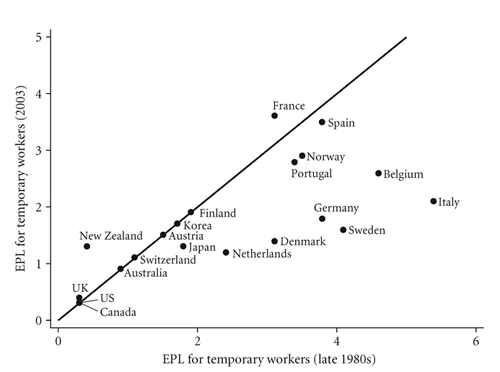

As presented in figures 1.1 and 1.2, CMEs like Germany, Japan, and Korea developed strong employment protection regimes compared with LMEs (e.g., the United Kingdom and the United States). Even under adverse economic conditions, CMEs have rarely changed the high levels of employment protection for regular workers over the past two decades. However, they extensively liberalized the labor market for temporary employment, accelerating the trend toward the rise of dualism—the division of labor into a dwindling group of regular workers (or insiders) with the privileges of internal labor markets and an increasing number of non-regular workers (or outsiders) more directly exposed to market forces (Brinton 2011; Palier and Thelen 2010; Rueda 2007; Thelen 2012).4

Japan and Korea shared similar institutional characteristics of strong employment protection regimes for regular workers and relatively weak employment protection for temporary workers, like other CMEs. For regular employment, both countries ranked medium-high in the rigidity of employment protection, measured by the OECD employment protection legislation (EPL) Index, with scores of 2.4 for both Japan and Korea (as of 2003). Although these two countries ranked at a medium level in employment protection for temporary workers, Japan had a slightly lower level of employment protection for temporary workers than Korea, whose gap in the levels of protection between regular workers and temporary workers was much greater than that in any other advanced industrialized country except for the Netherlands (OECD 2004, 110–117).

FIGURE 1.2 Employment protection regimes for temporary workers

Source: OECD (2004, 117).

Note: EPL refers to the scores of employment protection legislation measured by OECD; for Korea and New Zealand, the scores of the late 1980s are replaced by those of the late 1990s because of the availability of data.

In fact, labor market flexibility (or weak employment protection) does not always refer to job insecurity. For instance, in the early 1980s, the Netherlands advanced extensive labor market liberalization for temporary employment—especially part-time workers—in order to reduce unemployment rates and to enable female workers to balance work a...