![]()

Chapter 1

Flint-working areas and bifacial implement production at the Neolithic flint-mining sites in southern and eastern England

Robin Holgate

INTRODUCTION

The flint-mining sites in southern England are amongst the earliest known Neolithic sites in Britain. Excavations took place at Grimes Graves in Norfolk and Cissbury in West Sussex as early as the 1850s and 1860s, with the most recent excavations at flint-mining sites taking place at Grimes Graves, Harrow Hill and Long Down in the 1970s and 1980s (McNabb et al. 1996; Longworth et al. 2012; Baczkowski and Holgate 2017). Subsequent research has suggested that mining for flint was an episodic, possibly seasonal, small-scale activity restricted to a small number of favoured, possibly liminal, locations on the Wiltshire/Hampshire border and western Sussex in the Early Neolithic period where ‘special’ flint was extracted largely from the lower-most seams in order to fabricate mainly axe heads; during the Late Neolithic period a much wider range of bifacial implements was manufactured, including discoidal knives, with axe heads being relatively insignificant at Grimes Graves in Norfolk and, potentially, at some of the Wessex/Sussex sites (Gardiner 1990; Holgate 1995; Barber et al. 1999; Bishop 2012; Longworth et al. 2012).

The published accounts of investigations over the last 150 years, during which time over 40 shafts and 120 working areas had been excavated, are mainly concerned with the mines and the mining process (Barber et al. 1999; Baczkowski 2014). This paper discusses the flint-working processes and products, along with the operation and outcome of flint working, at the flint-mining sites in southern and eastern England.

THE SUSSEX FLINT-MINING SITES

A series of flint mines and working areas was investigated at Stoke Down, Long Down, Harrow Hill, Blackpatch, Cissbury and Church Hill, Findon in the 1920s–1960s (summarised in Pye 1968; Holgate 1995; Barber et al. 1999; Russell 2000). Further fieldwork then took place in the 1980s at Harrow Hill organised by Gale Sieveking on behalf of the Fourth International Flint Symposium and by Robin Holgate to assess plough damage at Long Down, Harrow Hill, Stoke Down and Church Hill, Findon on behalf of the then Department of the Environment. Whilst the fieldwork results have been published (McNabb et al. 1996; Baczkowski and Holgate 2017), this paper focuses on discussing further the development and management of flint working at these sites.

LONG DOWN

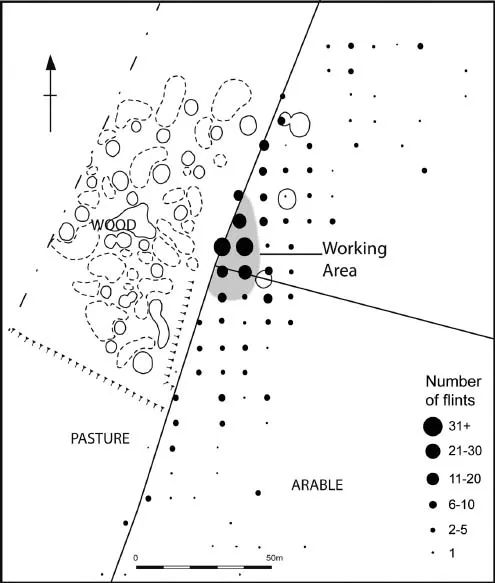

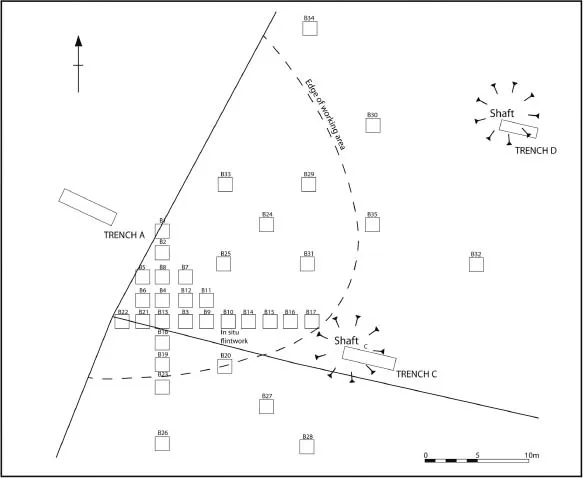

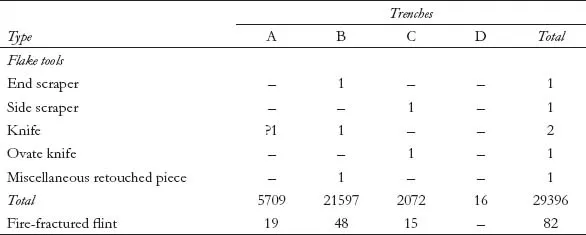

Between 1955 and 1958 E.F. Salisbury partially excavated a single shaft and investigated what he considered to be two flint-working areas at Long Down, the results of which he summarised in a brief report (Salisbury 1961). The fill of the shaft and the flint-working areas all produced unspecified quantities of flint debitage. Earthwork and surface artefact collection survey undertaken by Holgate in 1984 of the cultivated field immediately east of the main cluster of flint mines recovered predominantly debitage resulting from the production of bifacial implements fabricated on flint derived from the flint mines, as well as roughouts for two axes and an adze and an axe preform (see Table 1.1); this represents the remnants of an oval-shaped flint-working area measuring at least 25 m in diameter (Fig. 1.1). Two circular depressions c. 6 m in diameter were also recorded to the east of the flint-working area. Excavations in 1985 investigated the two circular depressions and the flint-working area, as well as what was interpreted as an upcast dump adjacent to the shaft excavated by Salisbury (Fig. 1.2). The trench (Fig. 1.2: trench A) by Salisbury’s shaft, rather than an upcast dump, revealed the upper fills of two shafts; the trenches sampling the two circular depressions east of the flint-working area (Fig. 1.2: trenches C and D) demonstrated that they were flint mines. Trenches were excavated to define the extent and nature of the flint-working area (Fig. 1.2: trenches B1–B35). An intact portion of the flint-working area survived measuring c. 12 m2 in area close to the edge of the present-day field. In total, 29,817 flints were recovered from both the survey in 1984 and the excavations in 1985 (see Tables 1.1 and 1.2).

The upper fill of two shafts adjacent to Salisbury’s excavation (trench A)

The trench by Salisbury’s shaft produced 5,709 flints (Table 1.2), mostly debitage. Of the flakes, 48% were hard hammer-struck: a higher proportion than that of the flakes recovered from the flint-working area (30%). Although soft hammer-struck axe-thinning or finishing flakes comprised 75% of all flakes and blades, this was a lower proportion than that recovered from the flint-working area (c. 90%). This, coupled with the fact that the upper fills of the mines produced a higher proportion of tested nodules (i.e. with only one or two flakes detached from them), quartered pieces or shattered pieces from the mine fills (7% compared with 0.3% from the flint-working area), sho ws that a significant proportion of the debitage from this trench was associated with the extraction and preparation of flint for making implements. However, the presence of axe-thinning and finishing flakes (64% of the flints), along with the roughouts for axes and a chisel, indicate that bifacial implements were being manufactured in this area or close by. The presence of clusters (described as ‘nests’ by Salisbury and others excavating flint mines in Sussex in the 1920s–1960s) of flakes and, in one instance, indicating an axe roughout, shows that piles of debitage were being dumped in this part of the site. Fragments of Early Neolithic pottery, probably Carinated Bowl, as well as an antler pick fragment and ox shoulder blade, were also recovered from the mine fills and radiocarbon-dated to the 39th to 38th centuries cal BC (Baczkowski and Holgate 2017, 16).

The isolated shafts on the eastern side (trenches C and D)

Sample excavation of the two shafts to the east of the flint-working area produced 2,088 flints (Table 1.2). In common with the flints recovered from the flint-working area, a significant majority from the southern of the two shafts (Fig. 1.2: trench C) derived from the production of bifacial implements: nearly 90% were soft hammer-struck axe-thinning or finishing flakes, along with three roughouts for two axes and a discoidal knife. All the flints recovered from the northern of the two shafts (Fig. 1.2: trench D), as well as 38% of flakes from the southern shaft (Fig. 1.2: trench C), were associated with the rough dressing of mined flint.

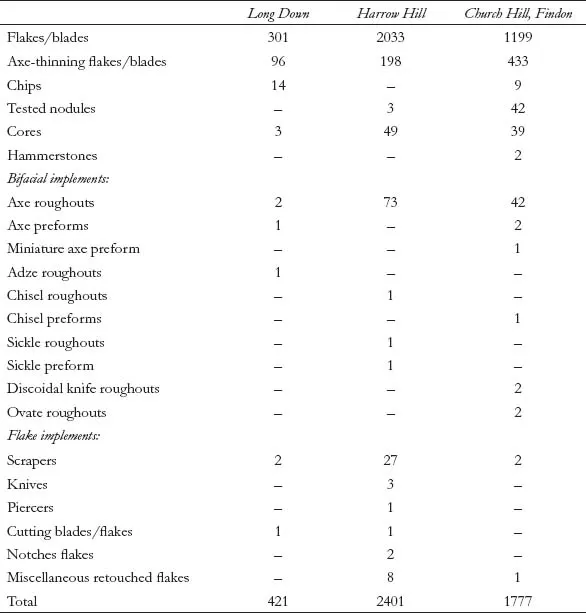

Table 1.1: Flintwork from the surface collection/recording surveys, 1984–5.

The flint-working area trenches (trenches B1–B35)

The flint-working area, occupying c. 650 m2, yielded 21,597 flints (Table 1.2). It is estimated that 4.2% of the flint-working area was excavated; assuming the same density of flints throughout, this would suggest that over 500,000 flints would originally have been left when the working area was abandoned. Some flints could date to the Later Bronze Age. The remainder all resulted from the production of bifacial implements from the flint mined at the site: 51% were soft hammer-struck thinning flakes, 39% were finishing flakes and 3% were chips; the roughouts were for six axes (one being a thin-butted axe) and three ovate or discoidal knives. The intact portion of the flint-working area contained 2,066 flints, of which 26% were hard hammer-struck flakes, 60% were soft hammer-stuck thinning flakes, 8% were finishing flakes and 5% were chips; two axe roughouts were recovered, along with fragments of Early Neolithic, probably Carinated Bowl, pottery which may have all originated from the same bowl found in the backfill layers adjacent to the shaft excavated by Salisbury. The ovate/discoidal knife roughouts which are usually dated to the Late Neolithic period suggest that, following the establishment of the flint-working area in the early fourth millennium cal BC, further working of flint to produce bifacial implements continued until the mid–late third millennium cal BC.

Fig 1.1: Long Down showing the flint-working area and the densities of flint recorded in the 1984 surface collection survey (after Baczkowski and Holgate 2017, fig. 4).

Fig 1.2: Long Down showing the location of the trenches excavated in 1985 (after Baczkowski and Holgate 2017, fig. 5).

HARROW HILL

In 1924 and 1925 a survey of the flint mines and excavation of a shaft (shaft 21) on the north side of Harrow Hill was directed by E. and E.C. Curwen (Curwen and Curwen 1926). They recovered ten small ‘nests’ of flakes, 54 broken or roughout implements and at least eight axe preforms. In 1936 George Holleyman excavated trenches across the late prehistoric enclosure on the summit of the Hill, which included investigating three shafts (Holleyman 1937), encountering ‘nests of flakes’ and at least 100 axe roughouts and preforms in the fill of the shafts but no remains of surface flint-working areas.

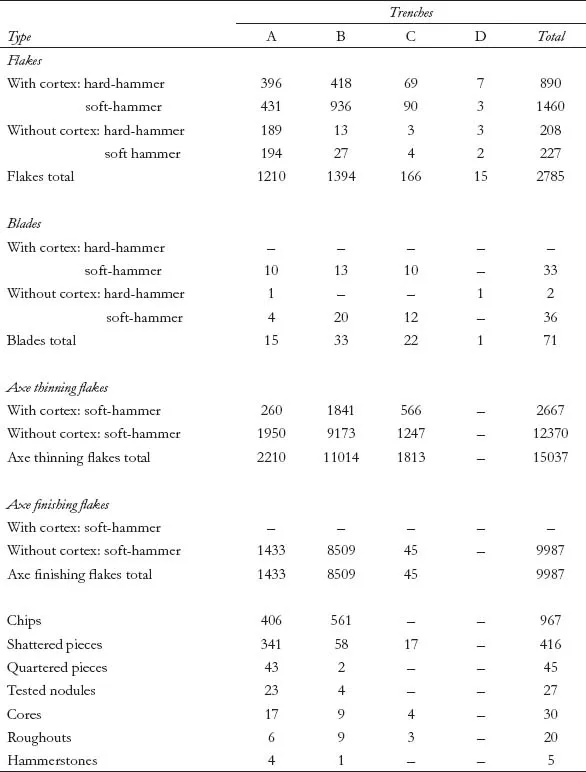

Table 1.2: The flintwork from Long Down, 1985.

In 1982 Sieveking arranged for P.J. Felder to excavate shaft 13, situated to the northwest of shaft 21, and in 1984 for Greg Bell to excavate three trenches alongside shaft 13 to investigate if any flint-working areas were located in this part of the site (McNabb et al. 1996). Surface artefact collection survey of the cultivated field on the south side of Harrow Hill undertaken by Holgate in 1985 identified a flint-working area c. 45 m in diameter which included a significant quantity of debitage and bifacial implement roughouts/preforms, predominantly axe roughouts, as well as two sickle roughout/performs (Baczkowski and Holgate 2017; Fig. 1.3 and Table 1.1). The north-west part of the area surveyed produced debitage and implements manufactured on flint originating close to the surface, which probably date to the Late Bronze Age. Seven circular depressions were also recorded (Fig. 3) and initially interpreted as shafts in the vicinity of the flint-working area. Sample excavations of these ‘depressions’, along with the flint-working area, were led by Holgate in 1986 (Baczkowski and Holgate 2017; Fig. 4). The excavations on both the northern and the southern part of the site produced a total of over 8,100 flints (see Tables 1.3 and 1.4).

North side of the Hill

Clusters of debitage (see Table 1.3), as well as two antler hammers, were discovered throughout the fill of the shaft excavated by Felder and from galleries radiating out from its base (McNabb et al. 1996, 35–7). Over 700 flints were recovered from the three trenches excavated by Bell adjacent to the shaft, the majority from the northernmost trench (trench 2: see Table 1.3). These flints are interpreted as resulting from individual episodes of fabricating axe roughouts/preforms, and not a flint-working area (McNabb et al. 1996, 28); the majority of f...