![]()

1

Memphis Monday Morning

1945–1948

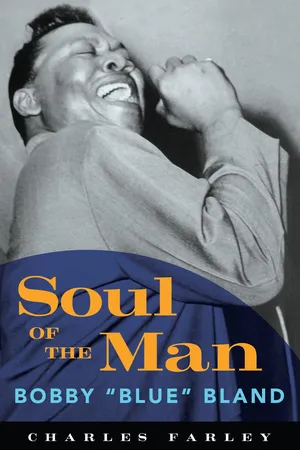

A young robert Bland at the microphone at WDIA in memphis, Tennessee, ca. 1950. Copyright ernest C. withers estate, courtesy Panopticon Gallery, Boston, MA.

When fifteen-year-old Robert Bland walked down Beale Street for the first time after his family moved to Memphis in 1945, he found a city filled with hope, racial division, and the music that would change America.

Robert was a shy country boy who was old enough and bright enough to know that Memphis held a whole new world of opportunity for him compared to the tiny rural cotton towns where he had grown up. Thankfully his mother agreed; she, in fact, was the one who had hatched the plan of moving to the city in the first place. She had experienced all her life the hard, daily grind of small-town, Jim Crow southern living and instinctively knew, especially with young Robert’s aversion to books and school, that he would likely end up in the cotton fields forever unless she did something soon. The only thing the boy seemed to enjoy doing was singing, and she thought perhaps he could best take advantage of this affinity if they moved to Memphis where there seemed to be music everywhere, even if a lot of it was not the church music that she so very much preferred.

So, soon after Mrs. Bland’s parents moved to Memphis and World War II ended with Japan’s surrender on August 14, the Bland family—young Robert, his mother, Mary Lee, and his stepfather, Leroy—made the twenty-two-mile move southwest from Barretville, Tennessee, to Memphis. The city on a bluff above the Mississippi River was now, according to the New York Times, “the cultural as well as the social and commercial capitol of a huge area of near-by Tennessee, Mississippi, Arkansas and Missouri.”1 They first lived with Mary Lee’s parents on Hill Street on Memphis’s north side, but soon moved to their own apartment downtown at 398 Vance Avenue, when Mary Lee found a job at the Firestone Plant on Thomas Street and Leroy landed a position at a foundry on the north side. Later, Leroy worked as a laborer at Samuel Furniture until he found easier work repairing juke boxes at Joe Cuoghi’s on Summer Avenue. Joe Cuoghi later became one of the founders of Hi Records, where Leroy’s stepson would make records in 1967 with the legendary soul producer Willie Mitchell.2

However, before all that was to occur, Robert had first to find his way in his new home town. His parents urged him to return to school. Booker T. Washington High School was not far from their apartment and recognized as one of the best secondary schools for young African Americans in the South. But Robert would have none of it. He had made it through only third grade in Rosemark, where the family had lived before moving to Barretville, and it had been a struggle to do that. The truth was that, between picking and chopping cotton almost year-round, he had attended classes only sporadically and had never even learned to read or write. So, in this pre-GED/adult education era, to a self-conscious adolescent newcomer, it seemed either entering high school, as unprepared as he was, or returning to elementary school, as old as he was, would be far more embarrassing than suffering the occasional indignities of living a life of illiteracy.

Besides, by now Robert was used to working and earning his own spending money, and school, he reasoned, would afford him little immediate opportunity to find a job that would help to support him and his family while he tried to forge some kind of career in music. So he scraped up enough to buy a second-hand bicycle and found a job delivering groceries from the little store on the corner of Vance and Hernando Streets, a few blocks from the Blands’ apartment. The job didn’t pay much, but with tips he made enough to begin saving for a car. The job also gave him the opportunity to explore his new neighborhood.3

Fortunately for Robert and his family the economy in Memphis was thriving. The price of cotton had doubled in the past five years.4 Robert and the veterans returning triumphantly from World War II looked on Memphis as the place in the mid-South to make their marks and to escape the cotton fields and rural poverty of the Delta’s Depression in which many of them were raised before the war. Here, they found a bustling, vibrant city of hope and possibility. Their hopes were not unfounded, as it turned out. By 1955, according to David L. Cohn, a Mississippi native who wrote in the September 4, 1955, issue of The New York Times, Memphis was “the nation’s largest inland cotton market, largest inland hardwood lumber market, largest producer of cottonseed products, and the country’s tenth largest wholesale center, with the prosperous population of nearly a half million.”5

But unfortunately not all of Memphis was equally affluent. Whereas the median income for white Memphis families in 1950 was $2,264, it was only $986 for black families (figures similar to Atlanta, Birmingham, and New Orleans).6 A 1940 WPA survey noted that 77 percent of Memphis’s black population lived in substandard housing, compared to 35 percent of the white citizenry, and less than 11 percent of black families had an indoor bathroom.7 The reality was that the black Memphis that young Robert Bland encountered in 1945 was largely cut off from the white majority of about 63 percent who actually owned, controlled, and ruled the city. “Like a whole city of Ralph Ellison’s invisible men and women, they were out of sight and out of the minds of most white people,” wrote Louis Cantor in his Wheelin’ on Beale.8

And while the South’s nasty brand of segregation was nothing new to Robert, he was surprised at some of Memphis’s racial peculiarities. Once he had mistakenly entered Jim’s Barber Shop, at the corner of Beale and Main, next to the Malco Theater, to get his hair cut, but was quickly ushered out, since Jim’s only cut the straight hair of white people even though all its employees were black.

He also soon learned that he could have lunch at one of the downtown department stores, Kress’s 5 & 10 or the Black and White Department Store, but he had to eat at a separate black-only counter. In 1947, Jackie Robinson would become the first African American to play major league baseball, winning the National League Rookie of the Year Award after a stellar season with the Brooklyn Dodgers, but in Memphis Robert was not allowed to watch the Memphis Chicks, the all-white Southern Association baseball team. Instead he often took in a Memphis Blues game at the African American Martin Stadium where the Blues hosted Black Southern Association rivals such as the Atlanta Black Crackers, the Birmingham Black Barons, and the Chattanooga Choo-Choos.9

Still, despite the economic and social inequalities that this separation of the races created, it also spawned an extraordinary breeding ground for African American creativity not only in the sports and entertainment worlds, but also in the arts, music, and business fields. And at the heart of this southern black renaissance was the street where Robert was to reside and grow into manhood during the next seven years. From the small apartment on Vance, the family moved the next year, 1946, to a larger unit at 304 Cynthia Place, just three blocks off Beale Street, the famous street that begins at the Mississippi River and runs east for about a mile.10

When, earlier in the twentieth century, the steamboats docked at the foot of Beale, passengers and roustabouts needed only walk a few steps to be met with dance halls, cafes, honky-tonks, booze, and blues. The street soon would be known worldwide, thanks primarily to a young man from Florence, Alabama, named W. C. Handy who immortalized Memphis and its rowdy thoroughfare in 1912 with his “Memphis Blues,” and in 1916 with his “Beale Street Blues.” Until its decline in the 1960s, Beale Street was the focal point of the Mississippi Delta and “the Main Street of Negro America,” observed George W. Lee, a Memphis insurance executive and author. “There are many other streets upon which the Negro lives and moves,” he wrote, “but only one Beale Street. As a breeding place of smoking, red-hot syncopation, compared to it, Harlem, State Street, and all the rest of the streets and communities of Negro America famed in story and song are but playthings.”11

Indeed, by the time a wide-eyed young Robert Bland was cycling around his neighborhood delivering groceries, Beale Street and its nearby environs was the one thing that southern African Americans could call their own—a community in which they felt comfortable shopping, entertaining, and communicating. It was a refuge for Robert and other southern black people from the daily degradation of the deep South’s humiliating stripe of segregation. “To Handy and untold other blacks,” Beale Street observers Margaret McKee and Fred Chisenhall wrote, “Beale became as much a symbol of escape from despair as had Harriet Tubman’s underground railroad. On Beale you could find surcease from sorrow; on Beale you could forget for a shining moment the burden of being black and celebrate being black; on Beale you could be a man, your own man; on Beale you could be free.”12

At first Robert’s mother feared for her son’s safety in the bustling city whose rough reputation as a city of sin was widely recognized. During Prohibition, Memphis was run by the political machine of E. H. “Boss” Crump who turned a blind eye to vice, gambling, and partying in the African American neighborhoods around Beale Street—as long as necessary payments were made, racial segregation was maintained, and nothing untoward spilled over into white sections of the city. But by the time the Blands took up residence in the city, it was no longer the South’s center of homicide and corruption. In response to state investigations of his alleged manipulation of black voters, Crump had clamped down on the violence, gambling, and prostitution that his political machine had largely protected in the earlier years of its reign. Now the city was relatively tame, although it seemed to young Robert, accustomed to the serenity of country living, that the party was still going on.

“Well, to say it lightly, there’s nothing light to say about Beale Street,” Bland recalled about the street. “It had everything that you would probably want to get into, from a good thrashing to all the fun you could handle and all the whatever. Beale Street was the place because if you were an out-of-towner you had always heard about Beale Street—the good and the bad, basically the bad, you know, something that travels faster than good. But it was a learning process for a lot of things. All the theaters were down there. You know, you couldn’t go Downtown because if you go to the Princess you’ve got to sit upstairs and also the Malco—they call it the Orpheum now. So didn’t too many travel up there because it was too high, actually. You could pay a quarter and go to the New Daisy and stay all day. You could stop at the One Minute and get five or six hot dogs and go in there and enjoy all the westerns because they played all day Saturdays. But, Beale Street, as I said, was a learning process for a lot of people and it’s got all the history in the world that you can think of—some good and some bad—but I can appreciate what I learned from the area.”13

Rufus Thomas was one of Robert’s best teachers. At the time he was emcee for the weekly Wednesday night amateur shows at the Palace Theater, and in 1986 he described the earlier scene like this: “But, talking about Beale Street—every neighborhood had its roughness, and Beale Street was no worse than any other. You didn’t have to go to Beale Street to die from a killing. But the collection of people that went to Beale Street was different. Beale was not a rich-man’s neighborhood. Nobody on Beale, the clientele, were rich. Now, they wore good clothes. They wore the best clothes that money could buy. Shoes shined to the bone—and whatever dress was fashionable at that time. Both man and women dressed up. The clothes I remember, they called ’em drapes. They had all those pleats in the front and pants legs were small at the bottom. They had big hats and they wore a long watch chain and they used to stand on the corner and twirl that chain. It was the zoot suit, the drape, we called it. I went on the radio, WDIA, in the 1950’s, and Beale Street was still flourishing. …”14

It was a perfect place for a young man like Robert Bland who was bored and fed up with his previous rural life and immediately heard something in the tone and tunes of Beale Street musicians that represented a feasible future for the ambitious teenager. One of the first performers that Robert met was another country boy, five years Robert’s senior, who was trying to forge a musical future in Memphis himself. His name was Riley B. King, later to be known as B.B. King, who recalled in his autobiography:

On Beale Street, you could get the whole meal for 20 cents. Beale Street had chili, best in the world, thick and rich and spicy delicious. Belly washers were huge quart bottles of flavored soda pop—cream or grape or peach—for washing down the chili. Grab you some chili at Mitchell’s Hotel or the One Minute Café. Or go to Johnny Mills’ Barbecue on the corner of Beale and Fourth …

There was a caring feeling on Beale Street. Musicians would talk to each other, exchange ideas, listen long and hard to each other. I learned so much just hanging ’round the park. Folks were friendly. They sensed your eagerness and opened their hearts, shared their experiences. I made some friends I’ve kept for life. Bobby Bland was one. He’s one of the only people I’ve stayed close to for over fifty years. He’s my favorite blues singer. Man can sing anything, but he gives the blues, with his gorgeous voice of satin, something it never had before. He lifts the blues and makes them his own. I got started a little before Bobby, but when he came ’round Beale Street I loved having him sit in with those little bands of mine. Bobby was one of the joys of Beale Street.

Beale Street was like WDIA. They were the hot spots for people who loved music and wanted to get somewhere. Seemed like these were the only places where the races really got along. They were islands of understanding in the middle of an ocean of prejudice.15

WDIA was a small, ailing radio station in Memphis when in 1948 its white owners, Bert Ferguson and Don Kern, in desperation, decided to switch its all-white format to a completely black format and become the first all-black radio station in the United States. And, although the station remained white-owned, the first black-hosted show aired at 4:00 p.m. on October 25, 1948, and by the end of 1949, there was not a white voice to be heard at 730 on most black Memphians’ AM radio dials. As Louis Cantor recounts in his excellent history of the station, Wheelin’ on Beale: “Claiming to reach an incredible ten percent of the total black population of the United States, WDIA was a celebration of firsts: the first radio station in the country with a format designed exclusively for a black audience; the first station south of the Mason-Dixon line to air a publicly recognized black disk jockey [Nat D. Williams]; the first all-black station in the nation to go 50,000 watts [in 1954]; the first Memphis station to gross a million dollars a year; the first in the country to present an open forum to discuss black problems; and, most important, the first to win the hearts and minds of the black community in Memphis and the Mid-South with its extraordinary public service. For most blacks living within broadcast range, WDIA was ‘their’ station.”16

It was also at WDIA where B.B. King got his start in 1949 as a disk jockey, and where B.B. and Robert would appear, initially without pay, in order to plug their own shows at local clubs. When the station went from being a local 250-watt, dawn-to-dusk operation to a 50,000-watt, 4:00 a.m.-to-midnight regional powerhouse in 1954, it claimed to be reaching 1,439,506 listeners in 115 counties in Arkansas, Mississippi, Missouri, and Tennessee. Performers, who may have enjoyed only local fame, were now being catapulted into national black consciousness. In addition to B.B. King and Bobby Bland, Rosco Gordon, Earl Forest, Joe Hill Louis, Willie Love, and Willie Nix were soon to gain national recognition, largely attributable to their airplay on WDIA. “WDIA did more to help...