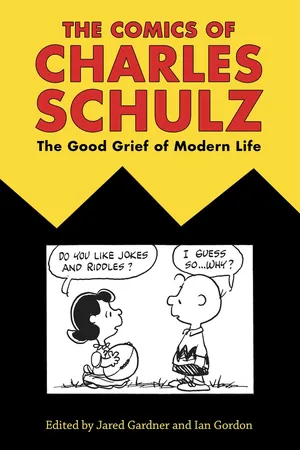

![]() TRANSMEDIAL PEANUTS

TRANSMEDIAL PEANUTS![]()

-10-

MAKING A WORLD FOR ALL OF GOD’S CHILDREN

A Charlie Brown Christmas and the Aesthetics of Doubt and Faith

BEN NOVOTNY OWEN

According to the standard story told by its creators, A Charlie Brown Christmas, one of the most familiar and well-loved American animated films, was expected to be a flop. Lee Mendelson, the producer, recalls that before the special aired the filmmakers were unsure whether they had made something good, and, worse, “the two top executives at CBS” were decidedly negative, seeing the film as “a little flat … a little slow.”1 The program of course went on to be very successful, both critically and commercially, taking the number two spot in the Nielsen ratings for the night it first aired on December 9, 1965, with an estimated fifteen million viewers (second only to the ratings juggernaut Bonanza), winning an Emmy and a Peabody Award, and inaugurating a series of more than forty television specials (as well as four theatrical movies, a Saturday morning cartoon series, and a television miniseries about US history). It still airs twice a year on ABC, and the soundtrack album by the Vince Guaraldi Trio has sold more than three million copies.

While there is no reason to doubt the version told by Mendelson and his partner Bill Melendez, who animated and directed A Charlie Brown Christmas (and all of the subsequent Peanuts specials until 2006), the story of near-failure works as a perfect origin myth. After all, the special’s emblematic story is about Charlie Brown choosing a small, misshapen Christmas tree among the painted aluminum trees to feature in his Christmas pageant, then being mocked by the other children for his blockheaded choice, until Linus reminds everyone of “what Christmas is all about,” at which point everyone learns to love the tree. The cartoon’s message about the tree is the same as the filmmakers’ message about the cartoon; although the animation had, in Melendez’s words, “so many warts and bumps and lumps and things,” the imperfections “seem to make it even more endearing to a lot of people.”2 Indeed, the special’s lack of polish, including its use of real children’s voices for the characters rather than adult actors, contributed to what Richard Burgheim, the reviewer for Time, called its “refreshingly low-key tone.”3 And the story that CBS executives were doubtful about its popular appeal potentially complements its anticommercial stance, even while broadcasts in the 1960s included plugs for Coca-Cola, which commissioned the special.

Fig. 10.1: Still from Rooty Toot Toot, dir. John Hubley (UPA, 1951).

Still, the success of A Charlie Brown Christmas poses several questions. If the special was successful as much because of its flaws as in spite of them, what elements resonated with the public, and why? One answer is simply that some of the things that made the special at best a modestly accomplished cartoon—the flatness of the characters and backgrounds, the recycling of sequences at different points in the film—allowed it to be a faithful rendition of the Peanuts comic strip, which was hugely popular at the time. Not only are the jokes and scenarios familiar to readers of the strip but the characters look very similar to Charles Schulz’s drawings, and this visual similarity was a relatively rare phenomenon in the history of animated adaptations of comic strips. For example, while Krazy Kat animated shorts followed the plot of the comic strip with varying degrees of faithfulness, even in the most similar, none of the characters ever looked much like George Herriman’s drawings.

On the production side, the directness of the visual adaptation was a matter of deliberate choices on Melendez’s and Schulz’s part, and on the reception side it was enabled by an audience taste for a flat, graphic style in animation. Viewers of A Charlie Brown Christmas were already familiar with the style of “limited animation” pioneered by artists working in and around the United Productions of America (UPA) animation studio from the late 1940s through the 1950s, a style deployed by many different studios by the mid-sixties. The flatness of this style allowed for a relatively straightforward transition from newspaper page to television screen, preserving the characteristic lines of Schulz’s world without warping them to accommodate the rounded volume of an animated body in the Disney or Warner Bros. mold. But where UPA made limited animation a sign of modernist sophistication, A Charlie Brown Christmas uses it to create a sketchy or unfinished appearance, thereby engendering a sense that the special was, as Burgheim described it, “unpretentious.” Melendez wished to make limited animation—an artistic style born of economic necessity—seem like a deliberate choice rather than a failure of quality.

In the best UPA cartoons, the artists involved accomplished this by employing art styles that included nods to various postimpressionist painters as well as to the sophisticated New Yorker illustrations of Saul Steinberg (which themselves assumed modernism as an established idiom, available for use, citation, and parody). Not merely derivative, however, UPA artists were also experimental in their techniques, as when background designer Paul Julian used a corroded gelatin roller to produce the distressed-looking backgrounds for director John Hubley’s masterpiece Rooty Toot Toot (1951) (fig. 10.1). Despite limited animation’s origins in economic considerations, a cartoon like Rooty Toot Toot drew on an enormous amount of labor and planning to produce its effects. For example, the studio hired the dancer Olga Lunick to choreograph the dance sequences.4 By contrast, Melendez, up against a six-month deadline to produce a half-hour special, could not necessarily create the polished look of a UPA short and so needed to create an alternative aesthetic of directness and sincerity.

The special’s soundtrack was key to creating this aesthetic. Taking his cue from the Maypo commercials made by John Hubley, Melendez directed the child actors who voiced the Peanuts characters to speak in a markedly unpolished, naturalistic manner. To some extent, the change in the connotations of limited animation—from modernist sophistication to unpolished “authenticity”—that we see on display in A Charlie Brown Christmas is characteristic of a shift in medium, as television rather than film became the primary focus of animation production, and budgets for animation shrank. Despite its origins in the 1940s as a cost-cutting measure, the virtuoso graphic design necessary for the sophisticated appearance of early-1950s UPA animations was impossible to produce cheaply, and the voice of the performer consequently became more important in compensation for restrictions on compelling visuals.5

But the unpolished aesthetic also goes some way to explaining the success of the program with a mid-1960s American audience (and audiences since). Both vocals and visuals continually remind us of their manufactured nature, and yet the effect is to strengthen rather than weaken the special’s claim to a form of spiritual truth. A Charlie Brown Christmas regularly oscillates between two contradictory kinds of truth claim—a naturalistic investment in presenting kids as they are, and a stylistic breaking of the “the illusion of life” produced by Disney-style realism.6 But unlike avant-garde works in which the demystification of the illusion of life is an end in itself, in the Charlie Brown special, skepticism is a prerequisite for communicating certainty. The early Peanuts animations spoke to an audience who wanted trust to emerge from an openness to interpretation, and not from the overemphatic explanation of the hard sell.

This conception of truth is best exemplified by Linus’s famous recitation of Luke 2:8–12 from the King James Version to an almost empty auditorium, a statement of Christian belief left without a settled explanation of meaning. The special’s combination of unpolished simplicity and anti-illusionism fit well with the new idiom of advertising in the mid-1960s, which aimed to address an increasingly skeptical, media-savvy audience. As a television program commissioned by Coca-Cola, using animated characters originally created in 1959 to sell the Ford Falcon, A Charlie Brown Christmas countered its own status as an advertisement with a message of anticommercialism and an unfinished visual style that attempted to engage the viewer on terms of equality.

Bill Melendez created the look of the Peanuts specials, reworking Schulz’s drawings for a new medium. Melendez started in animation at Disney in 1938, working on many shorts and several features including Pinocchio (1940), Dumbo (1941), and Bambi (1942). He took part in the animators’ strike of 1941, after which he left Disney for Leon Schlesinger Cartoons, which later became Warner Bros.7 He began working for UPA in 1948 and contributed to some of their best-known shorts, including the classic Gerald McBoing-Boing (1950). In the late 1950s and early 1960s, he worked at Playhouse Pictures producing animated commercials for various companies, including Ford. His collaboration with Schulz began in 1959, when he animated the first in a series of ads for the new Ford Falcon model of compact cars featuring the Peanuts characters.8 He and Schulz continued to work together for the next forty-one years.

Melendez’s principle challenge in creating the Peanuts commercials was to figure out how to animate “a cartoon design, a flat design,” which he “had always wanted to do.”9 Peanuts’ “flat design” meant, in this context, that in the newspaper strip the characters tended to exist in certain specific positions, mostly either in profile or in three-quarter view. They did not have the “roundness” of, say, a Warner Bros. character because, unlike Bugs Bunny, they were not understood as three-dimensional entities and so would never appear from a full range of angles. Because of this, Melendez became adept at animating Schulz’s characters so that “you wouldn’t see the turns,” and they existed for almost all of their screen time in positions familiar from the comic strip. According to Melendez, this was actually something Schulz required, regarding views of the characters from other angles as bad drawings.10 As David Michaelis writes, the former Disney animator Melendez “earned Schulz’s respect by not Disneyfying the Peanuts gang when he made the Ford commercials,” and that Schulz trusted Melendez “to place Charlie Brown and the others into animation without changing their essential qualities, either as ‘flat’ cartoon characters or as his cartoon characters.”11

The limitations on the Peanuts characters’ dimensionality and movement presented particular challenges for Melendez.12 The characters couldn’t reach above their heads, for example, and so in moments when this was required, such as during the decoration of Charlie Brown’s tiny Christmas tree at the end of the film, he drew the characters facing away from the viewer in a clump. Their arms disassociate from their bodies in a flurry of activity to distract from the basic implausibility of the motion. By 1959, Melendez was very experienced in animating flat design. His former employer, UPA, was the pioneer of what came to be known, pejoratively, as limited animation, and with it a type of modern design that by the mid-1950s had become the critical “reference point” for new animation.13 Best understood as a deliberate departure from Disney-style animation, which tended to function as the standard for the industry from the late 1920s onward, limited animation refers to a group of practices designed to limit the number of drawings and frames used in animation, thus reducing the cost of production. At UPA this meant, among other things, that animators supplied one drawing for every two frames of animation (as opposed to one drawing for every frame), and also that they departed from the traditional animation approach of using three parts for every on-screen action—anticipation, the action itself, and follow-through. UPA animators tended to cut the anticipation phase.14

Limited animation came to be associated with shoddy-looking television animation in the 1960s, as studios stopped producing the theatrical animated shorts that had been the industry standard since the earliest days of animation. But in its richest sense it also referred to an attempt to treat economic restriction as an enabling condition for artistic experiment. Understood in this way by animators at UPA in the late 1940s and early 1950s, limited animation meant a new emphasis on graphic design as a primary consideration of animation, ideally giving animated cartoons a sophisticated graphic logic. At its theoretical edges, the UPA approach to animation was an artistic expression of cofounder Zack Schwartz’s observation that “[o]ur camera isn’t a motion-picture camera. Our camera is closer to a printing press.”15 Animators at UPA, and others working in a similar idiom, self-consciously aligned their work with modern art, particularly with the sophisticated print graphics of illustrators like Saul Steinberg.

The Peanuts animations belong to this tradition. Besides the graphic flatness of its characters, A Charlie Brown Christmas shows its roots in midcentury limited animation in part through the choppiness of its animation, which emphasizes expressive poses rather than the smooth movement between those poses. We can see this in the repeated shots of the characters dancing and playing music on stage, while Guaraldi’s “Linus and Lucy” plays. And the UPA style also appears in the use of abstracted backgrounds, which show brush marks and other signs of their manufacture, do not employ point perspective, and include objects that appear as geometric blocks of paint, without shading or other modeling (fig. 10.2).

By the end of the 1950s, financial troubles and a change in ownership ended UPA’s reputation as an artistic innovator, but the look of designcentric, flat animation was already an integrated feature of work from other studios, including Disney. The style is evident in the short Pigs Is Pigs (1954), and in the features Sleeping Beauty (1959) and 101 Dalmatians (1961).16 The familiarity of the flat aesthetic in animation by the late 1950s was a necessary condition for the creation of the Peanuts Ford commercials, and later the specials, since it enabled comics characters’ transition from newspaper to television without them having to be reimagined as voluminous, spheroid bodies. This gave Peanuts a strong aesthetic identity across media. As Leon Morse wrote in his review for Variety, “the animation was intentionally uncomplicated so that the characters did not lose their basic comic strip identity.”17 Peanuts remained a coherent brand in which the newspaper strip served as the template for subsequent iterations. The visual similarity between strip and TV program reinforces other elements taken directly from the strip. The majority of jokes in the special are in fact from the newspaper strip. For example, Lucy’s complaint that she never gets what she really wants for Christmas, “real estate,” is a version of a gag from the September 18, 1961, strip. And when Charlie Brown yells “Don’t you know sarcasm when you hear it!” after Violet, he’s repeating a joke that originated in the December 27, 1962, strip.

Fig. 10.2: Still from A Charlie Brown Christmas, dir. Bill M...