![]()

1 Oak-dominated Ecosystems

Introduction

We are still in transition from the notion of man as master of the earth to the notion of man as part of it.

(Wallace Stegner, 1995)

A truly ecological perspective recognizes that humans and their activities are part of nature, and that enhancing all aspects of their lives – including their surroundings – begins with cooperation between individuals, based on mutual trust …

(Alston Chase, 1995)

From earliest times, oaks have held a prominent place in human culture. Their uses have included wood for fuel, acorns for hog fodder and flour meal for human consumption, bark for tanning, wood strips for weaving baskets, charcoal for smelting ore, timbers for shipbuilding, mining timbers, railroad ties, pulpwood for paper, and lumber and laminates for furniture, panelling and flooring. Through the mid-19th century, oak was the wood of choice for shipbuilding in Europe and America. For that reason, oak forests and even individual trees were treated as critical national assets. During the Revolutionary War, the poor condition of the British fleet, which lacked replacements and repairs due to shortages of suitable oak timbers, may have contributed to the war’s outcome (Thirgood, 1971). In the 17th century, alarm over the depletion of timber supplies, especially oak, prompted passage and enforcement of laws mandating the protection, culture and establishment of forests in several European countries. In turn, those events influenced the development of scientific silviculture, as we know it today.

Modern as well as ancient man has benefited from the oak’s relation to wildlife. Wherever oaks occur as a prominent feature of the landscape, wildlife populations rise and fall with the cyclic production of acorns. Numerous species of birds and mammals are dependent on acorns during the food-scarce autumn and winter months. Even human cultures have relied on oaks as a staple food. Acorns were an important part of the diet of Native Americans in California before the 20th century (Kroeber, 1925) (Fig. 1.1). Today, the ecological role of oaks in sustaining wildlife, biodiversity and landscape aesthetics directly affects the quality of human life. But while all that is known, putting our knowledge of oaks into a comprehensive value framework that is understandable and acceptable to most people has remained elusive (Starrs, 2002).

The demand for wood products from oaks nevertheless continues to increase and compete with other less tangible values. Some have proposed that forests, including those dominated by oaks, are best allowed to develop naturally, free from human disturbance. What should the balance be among timber, wildlife, water, recreation and other forest values? Is there some middle ground that adequately sustains multiple goals? Informed answers and perspectives require an understanding of the ecology of oaks and the historical role that humans have had in that ecology, especially the comparatively recent role of humans in the ‘protection’ of oak forests from fire. A prerequisite to such understanding is a general knowledge of the oak’s geographical occurrence, taxonomic diversity, adaptations to diverse environments, and the historical changes in its environment.

The Taxonomy of Oaks

Taxonomically, the oaks are in the genus Quercus in the family Fagaceae (beech family). Members migrated and diverged into the current living genera by the late Cretaceous period (about 60 million years ago). By that time, mammals and birds had only recently evolved. Rapid speciation of oaks commenced in the middle Eocene epoch (40–60 million years ago). This was in response to the expansion of drier and colder climates, and subsequently to increased topographic diversity in the late Cenozoic era (< 20 million years ago) and fluctuating climates during the Quaternary period (< 2 million years ago) (Axelrod, 1983).

Their fruit, the acorn, distinguishes the oaks from other members of the beech family (e.g. the beeches and chestnuts). With one exception, all plants that produce acorns are oaks. The exception is the genus Lithocarpus, which includes the tanoak of Oregon and California. Although represented by only one North American species, Lithocarpus is represented by 100–200 species in Asia (Nixon, 1997a). Lithocarpus may be an evolutionary link between the chestnut and the oak (McMinn, 1964; cf. Miller and Lamb, 1985: p. 200).

Worldwide there are about 400 species of oaks, and they are taxonomically divided into three groups: (i) the red oak group (Quercus section Lobatae1); (ii) the white oak group (Quercus section Quercus2); and (iii) the intermediate group (Quercus section Protobalanus3) (Tucker, 1980; Jensen, 1997; Manos, 1997; Nixon, 1997b; Nixon and Muller, 1997). All three groups include tree and shrub species. The red oaks and white oaks include evergreen and deciduous species, whereas the intermediate oaks are all evergreen. The red oaks are found only in the western hemisphere where their north–south range extends from Canada to Colombia. In contrast, the white oaks are widely distributed across the northern hemisphere. The intermediate group comprises only five species, all of which occur within south-western USA and north-western Mexico. Many of the world’s oaks occur in regions with arid climates, including Mexico, North Africa and Eurasia, where they are often limited in stature to shrubs and small trees. About 80% of the world’s oaks occur below 35° north latitude and fewer than 2% (six or seven species) reach 50° (Axelrod, 1983).

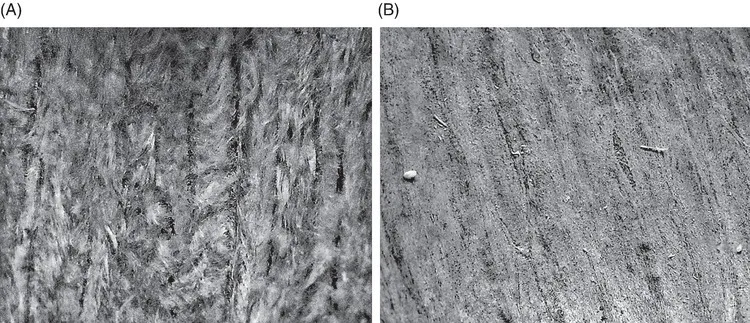

The most reliable distinction between the white oaks and red oaks is the inner surface of the acorn shell. In the white oaks it is glabrous (hairless) or nearly so, whereas in the red oaks it is conspicuously tomentose (hairy or velvety) (Tucker, 1980) (Fig. 1.2). In the intermediate group, this characteristic is not consistent among species. The leaves of the white oaks are usually rounded and without bristle tips whereas the leaf lobes of the red oaks are usually pointed and often bristle tipped. To many silviculturists, ecologists and wildlife biologists, the most important difference between the white oaks and red oaks is the length of the acorn maturation period. Acorns of species in the white oak group require one season to mature whereas species in the intermediate and most of the red oak group require two seasons. The white oaks and intermediate oaks are characterized by the presence of tyloses (occlusions) in the latewood vessels (water-conducting cells) whereas tyloses are usually absent in the red oaks. These vessel-plugging materials confer greater decay resistance to the wood of the white and intermediate oaks than the red oaks, and make them uniquely suited for production of tight cooperage. Other morphological features that differentiate the three groups and species within them are presented in various taxonomic treatments (e.g. Tucker, 1980; Jensen, 1997; Manos, 1997; Nixon and Muller, 1997; Hardin et al., 2001) and field identification guides (e.g. Miller and Lamb, 1985; Petrides, 1988; Petrides and Petrides, 1992; Stein et al., 2003). These sources also include range maps. In addition, the Silvics of North America, Vol. 2 (Burns and Honkala, 1990) provides information on the silvics and geographic ranges of 25 oaks. See also online references: Burns and Honkala (1990), USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (2008) and USDA Forest Service (2008). United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Forest Service publications can be accessed online via http://www.treesearch.fs.fed.us/

Of the more than 250 oak species occurring in the western hemisphere, the largest number occurs in Mexico and Central America, with only about ten species in Canada. In the USA and Mexico, the oaks collectively have greater species richness and greater biomass than any other genus of trees. Oak species comprise 20% of the woody forest biomass in the USA and nearly 30% in Mexico. Oak species richness increases from north to south across North America. Although northern oak species are fewer in number, they have greater biomass per species than the more numerous oak species with smaller geographic ranges found in Mexico and Central America (Cavender-Bares, 2016).

Recent genetic studies have concluded that the red oak and white oak groups (or clades) in North America evolved from common ancestors in northern Canada some 45 million years ago. Ten to 20 million years ago in western North America the two oak groups gradually migrated south into what is now California, while in the east the two oak groups also migrated south, spreading throughout the eastern USA and then into Mexico and Central America. There the rate of speciation accelerated along moisture gradients leading to the high species richness in those locales (Hipp et al., 2018). The exceptionally large, overlappi...