![]()

II. Waiting for news

Night and day I cry

I sit in million torments

and millions more I fear.

Andreas Gryphius (1616-1664)

1. Uprooted and torn

The escape

When Hitler seized power in 1933, it did not affect the Czech neighbors at first.

Whereas the Getreuer family in Schwanenbrückl noticed the boycotts against the Reich’s Jews, which started immediately. They felt safe in Czechoslovakia, but worried about their numerous relations in Munich because of the frightening Nuremberg Laws (Nürnberger Gesetze) of 1935 and the elimination of Jews from public life by the so-called Jews’ Laws, (Judengesetze, laws affecting Jews). From a presumably safe distance they watched Germany’s apparent rise to power. Walter wrote about these developments in his diary:

Incredibly fast and victorious is the rise of this man, unquestionably vested with political instincts. One has to admit, although he is inflicting a lot of wretchedness on mankind, in his own way he is bringing supernatural achievements to his people, to his Germany.

Being a sports lover himself, Walter was awed by the 1936 Olympic Games’ perfect organisation. He surveyed their every detail, noted the scores in his diary and called them the “best games ever”. He journeyed to Germany many times himself. But nothing of concern happened either while touring the Sudeten Mountains (Riesengebirge) nor during his trips to Bavaria. What he “had seen from the outside was pretty and good” and none of the Hitler supporters bothered him, he recounted in his diary.

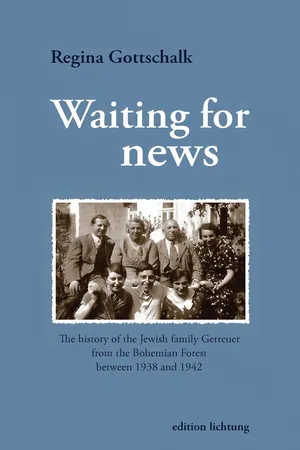

In the summer of 1938 the Getreuer family was unlikely aware of how soon their entire world would meet its downfall. A picture taken in August 1938, depicts once more a summer idyll in the garden: Visitors have arrived. A book lies on a wooden bench, it is possible the photographer had been reading it before he took the snapshot. In a deckchair next to it Paul Lustig, a nephew of the family, is sunbathing. To his right his little son Thomas, his wife Irene and niece Alice (“Liesl”) Epstein squint into the camera. Heinrich Getreuer has joined them. It must be hot, he has taken off his blazer – “everybody smile” – and is sitting in his shirt sleeves on the bench. In front Greif, the family’s gigantic dog, has made himself comfortable.

A few weeks later everything is over: The Munich Agreement (Münchner Abkommen) has been signed, the Sudetenland – which Schwanenbrückl is a part of – is annexed to the German Reich. Walter Getreuer notes in his diary: “The signs of this development we did ignore, trusting adamantly in our so-called friends.” Hitler’s speech on the 12th of September hinted the annexation of the Sudetenland to Germany, this was also heard on the radio in the Getreuer house, without arousing much excitement. Walter wrote in his diary:

We switched off the radio while heaving sighs of relief, when we heard loud noises from outside “ein Reich, ein Volk, ein Führer” (One empire, one people, one leader) – “Heil unserm Führer” (Long live our leader) – “Heil Hitler” (Long live Hitler) etc., etc. Quickly I ran outside into the front yard to hear everything properly. The young people marched through Schwanenbrückl, led by the people from the neighbouring village Althütte, who, naturally, shouted the loudest. I was expecting windows to break any moment, but nothing of the sort happened. Bit by bit the noises faded in the distance, once again silence prevailed.

The day after – it was Monday the 13th of September – Walter set out on a motorcycle journey, which he had been planning for a long time, to visit his relatives in Karlsbad. In vain his mother had tried to prevent the carefree young man from going on that trip. But once he had hit the road it dawned on him, how serious the situation really was:

It was in Plan (Planá) where I first noticed many people standing in groups talking eagerly, then, in Petschau (Bečov nad Teplou) I suddenly saw the first red swastika flag waving from a house. By now I got a little suspicious. Uncle Ludwig received me with great surprise, how dare I come to Karlsbad on a day like this. Everything was in great turmoil; Aunt Elsa, Aunt Trude and Leo had already left for Prague, and Uncle was prepared to leave within the next few hours. Rumours were buzzing around that Hitler would invade today, in Eger martial law had been enforced already, etc. Despite the incessant coming and going of agitated visitors breaking all sorts of horrible news to us, I managed to calm Uncle again and again, so that in the end we even made it into town. Quite a few things I saw made me think. Groups of wildly gesturing people were to be seen everywhere. Wardens with swastika armlets drove up and down on bicycles and motorbikes. Jews were laughed at with snide looks and now and then you could overhear remarks like “Go to Palestine!” and the like. A sinister mood was hovering above everything, there was something in the air. Nevertheless I was not willing to leave, until we met Schweinitzer Slawin begging us to leave, with tears in his eyes. Apparently, in Fischern, Jews had already been beaten and Hitler’s invasion was to happen any hour. Now Uncle was not to be stopped. He immediately called for a car, I grabbed my motorbike and in a hurry left for Prague at 5 p.m. …

On his way to Prague, Walter met Czech soldiers on their way to defend their country against the threatening German invasion:

I was in unspeakable awe, my chest had filled with fighting courage, and again and again with bright eyes I shouted to our green boys “Nazdar, Zdar Československu” [sic!] (salvation, salvation to Czechoslovakia) etc. This night is one I will never forget, touching like none before it, shaking sacred emotions of those who love their country, willing to sacrifice everything, everything for the homeland.

Late in the evening he arrived in Prague at his uncle Friedrich Lustig’s house. There he met further restless relatives who had fled the Sudetenland. Next morning, it was a Wednesday, Walter carried on to Teplitz-Schönau to stop by his sister Rose Abeles and her family. He learned that his family in Schwanenbrückl had fled in panic to Pilsen that very day. The day after Hitler’s speech, Heinrich had gone on a business trip to Pilsen. There his nephew Paul Lustig convinced him to immediately move his family to the Czech heartland, as countless Jews did in these days.

What had happened in Schwanenbrückl in the meantime, was written down by Louise Getreuer in her memoirs:

September 14th […] father decided to flee to Pilsen. While my parents waited in the car, ready to leave, I was surrounded by villagers offering to protect me, in case I decided to stay. The mayor offered to stand surety for me, and many offered to let me live in their houses. They truly liked me, and I nearly stayed to be killed later – but father forced me to leave – for good.

Herr Hogen, our butcher, owned a truck which we loaded with two beds, two sofas, bedding and clothes. Father drove it to Pilsen, while mother and I took the car. Arriving in Pilsen, we found the city prepared for war. Having taken his family to Irene’s brother in a small Czech village, our cousin Paul Lustig offered to let us stay in his flat. We were in great distress as we could not find our Walter. Walter arrived in Pilsen on Thursday, the day after their escape. He thought their departure was an over-hasty step – “over-hasty running away” he called it. But now it was too late to undo. Before leaving, Heinrich had put the house and the business into the hands of a man called Wartha, someone he obviously trusted. He was to sell his property as soon as possible. That same Thursday Walter and Louise went back to Schwanenbrückl to find out if the property could be sold and to fetch more items from the house.

Walter writes:

Panic prevailed in the village because of our departure […] our shop was packed with people buying as much as they could, although no one seemed to know where to find the articles or what their prices were. Girgl was devastated, as the day before people had allegedly tried to raid the shop. Neither Wartha, his wife nor his apprentices were capable of dealing with this situation, so to make a long story short, when Louise and I finally arrived in the morning everyone was relieved and for the very last time in our entire lives, we managed our beautiful shop.

For Walter it was hard to say goodbye to Schwanenbrückl:

Never will I forget my last day in Schwanenbrückl. Sad faces everywhere, villagers saying they hated to see us go, our Schwanenbrückl people showing their loyalty and love a hundred-fold, it nearly made me choke. And when Buzerfranz told me in his innocent, childlike voice: “it’s a pity for you”, I could not but run into the garden so I might cry […] The family was no longer able to sell their estate lawfully. No notary was to be found and the banks had been closed. On Sunday the 18th of September, only one week after Hitler’s Nuremberg speech, Heinrich and his daughter Louise drove to Schwanenbrückl one more time and handed over the house keys to Wartha. The family had thus lost its home.

Temporarily accommodated in Pilsen, the refugees tried to adapt to the new situation. They had put their household goods and the furniture they had been able to secure in storage with an agent. Frieda’s sister Martha Epstein and her husband Ernst, along with their 13-year-old daughter Alice (Liesl), had also found refuge in their relatives’ apartment. Nevertheless an alternative solution had to be found before the owners came back. It was hopeless to try to find accommodation in Pilsen as thousands of refugees had to bear the same lot. Not even a hotel room was available.

A letter from Frieda to her oldest daughter Rose Abeles, who had also fled from Teplitz-Schönau with her husband and daughter to Prague immediately after the Munich Agreement (Münchner Abkommen), gives us an idea of how desperate the Sudeten-German Jews must have been during the days following their escape. This letter is the first preserved one, written by Frieda to one of her children:

You have no idea what’s going on with [Jews] around here, all are from our region. Mandlers are still outside, most of them not knowing where to go. Yesterday Papa met Marie Beck at the railroad station, I heard she was crying bitterly. They had sold their house but had received no money from the man […]

I am […] happy that I can move about, I feel it in my foot, but my nerves are still good. Louise is also very brave, she achieves miracles. Our laces have been confiscated, God knows if we will ever be able to take some with us. […] Papa told us about the cheering that was going on outside, people aren’t working at all, everything has been flagged. Stay there still [undecipherable word], it’s good Ruthchen goes to school, that keeps her busy. This year it’s better not to think about the holidays. I’m afraid all the praying and wailing will not help us Jews anymore, we are a lost people. The only thing we can hope for is staying healthy, so we may endure all we have been burdened with. How often I have said these days, how wonderful it is that our child rests in peace. I wish we could be with her, how much better we would be off. Maybe we will never ever get the chance to visit her grave […]

Be kissed with all my love, your worried Mother.

Ill. 23: The last summer in Schwanenbrückl: Heinrich Getreuer (left) and visiting family members, August 1938

Searching for a future

In September the family moved from Pilsen to Prague. In the beginning the parents and Louise lived in a furnished room which Walter had rented for the winter semester. He himself had been drafted for medical service in Pilsen. The three people from Schwanenbrückl lived simply in the little student flat. They dined out in cafés, or fixed simple meals on a stove.

Two weeks later they were able to find a bigger place in Fochová 60. This must have been the last accommodation which they chose for themselves, before they were committed to a so- called Jews’ acccommodation (Judenwohnung). In her memoirs Louise describes these times:

I did my best to furbish the place with our rescued furniture, scrubbed the floor, did the laundry in the basement and carried it up three flights of stairs to the attic to dry. The water pipes, which ran through the oven, became hot when cooking and heated the room. To make coffee and tea, or to heat up food, we even had a gas cooker.

For now the family was safe, but what would the future bring? The younger generation did not doubt that Czechoslovakia would not be a safe country for Jews in the long run.

In autumn Walter wrote in his diary:

After what has happened recently, we Jews must finally be aware of the fact that we have to find a new home overseas, as we simply cannot wait for the war to break out, which alone can rescue us.

Immediately after the events in autumn 1938, all three Getreuer children endeavoured to immigrate into the United States of America. Rose and Josef Abeles and their daughter Ruth had the best chance of getting visas through the German quota within a relatively short time. In Munich, in June 1938, Josef’s parents and siblings had become victims of the usual smear campaigns against Jews in the journal Der Stürmer. The son, Josef, and his wife fled the Reich with their daughter, to find refuge in Czechoslovakia. After the Munich Agreement (Münchner Abkommen), the family fled their new home in Teplitz-Schönau, which had become German territory, and went to Prague.

Their shop in Teplitz-Schönau was closed, their apartment was confiscated. Without any scruple party officials seized their property and grew rich at their expense. When the war was over, Erwin Beneš, the Czech friend whom they had entrusted with their keys, told them that he had stood no chance in preventing the Nazis from taking whatever they liked. It was the bookcase the NSDAP official had shown particular interest in. Erwin himself had been threatened when protesting against their looting, and he was told that Jewish property was none of his business.

The Abeles family stopped temporarily at an aunt’s, to wait for the permit to immigrate to the USA. The compulsory declaration of surety was provided by their American relatives. In autumn 1938 Walter was also left with nothing. He had passed his preliminary examination in the summer, and during the holidays had finished an internship in Schüttenhofen (Sušice) hospital. On the 7th of November – before the German occupation! – he was expelled from the German University in Prague, for being Jewish. A curt entry, added to his university register form by the medical faculty, had ended his c...