The Ancient Art of Transformation

Case Studies from Mediterranean Contexts

- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

The Ancient Art of Transformation

Case Studies from Mediterranean Contexts

About this book

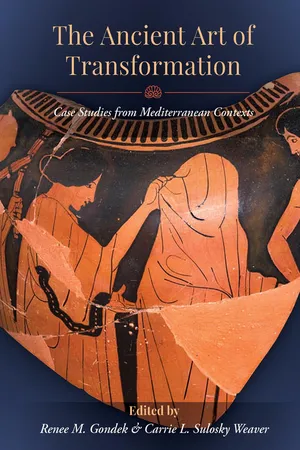

The Ancient Art of Transformation: Case Studies from Mediterranean Contexts examines instances of human transformation in the ancient and early Christian Mediterranean world by exploring the ways in which art impacts, aids, or provides evidence for physical, spiritual, personal, and social transitions. Building on Arnold van Gennep's notion of universal rites of passage, papers in this volume expand the definition of "transformation" to include widespread transitions such as shifts in political establishments and changes in cultural identity. In considering these broadly defined "passages, " authors have observed particular changes in the visual record, whether they be manifest, enigmatic, or symbolic. While several papers address transitions that are incomplete, resulting in intermediary, hybrid states, others suggest that the medium itself can be integral to interpreting a transition, and in some cases, be itself transformed. Together, the volume covers not only a broad chronological span (c. 5th century BC to 4th century AD), but also an expansive geographical range (Egypt, Greece, and Italy). Reflecting upon issues central to a variety of Mediterranean cultures (Egyptians, Etruscans, Greeks, Romans, and early Christians), The Ancient Art of Transformation documents how personal, societal, and historical changes become permanently fixed in the material record.? The Ancient Art of Transformation examines the visual manifestation of human transformation in the ancient and early medieval Mediterranean world, exploring the role of art and visual culture in enabling, hindering, or documenting physical, spiritual, personal, and social transitions such as pregnancy and birth, initiations, marriage, death and funerals. The definition of "transformation" is also expanded to address instances of less personal and more widespread transitions such as shifts in political establishments and changes in cultural identity in geographic locations. Additionally, although the ancient material record documents certain rites of passage such as marriage and death extensively, artifacts and their accompanying images are often studied simply to reconstruct these social processes. Authors here suggest that material evidence itself can be integral to interpreting a transition, and in some cases, be itself transformed. Further, several papers address transitions that are incomplete, resulting in intermediary, hybrid states that are very often reflected in the visual record such as Athenian vase-painting imagery forecasting the bride as a mother, displays of nudity that reflect intermediate life stages in Etruscan art and Octavian's visual transformation into Pharaoh and Augustus in Egyptian architecture and material culture. At its core the volume establishes current methods for understanding how ancient visual culture shaped, informed, and was affected by processes of transformation. Together, these papers offer a close examination of various types of visual evidence from several cultures and periods (e.g., Etruscan, Greek, Roman, early Christian), and document how personal, societal, and historical changes become permanently fixed in the material record.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Chapter 1

On the threshold of old age: perceptions of the elderly in Athenian red-figure vase-painting

Introduction

Literary perceptions of old age

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Abbreviations

- Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Approaching Transformation Renee M. Gondek and Carrie L. Sulosky Weaver

- 1. On the Threshold of Old Age: Perceptions of the Elderly in Athenian Red-Figure Vase-Painting Nicholas A. Harokopos

- 2. The Transformation of the Bride in Attic Vase-Painting Victoria Sabetai

- 3. Transitory Nudity: Life Changes in Etruscan Art Bridget Sandhoff

- 4. Cultural Manoeuvring in the Elite Tombs of Ptolemaic Egypt Sara E. Cole

- 5. Octavian Transformed as Pharaoh and as Emperor Augustus Erin A. Peters

- 6. Ethnic Identity, Social Identity, and the Aesthetics of Sameness in the Funerary Monuments of Roman Freedmen Devon Stewart

- 7. Greater in Death: The Transformative Effect of Convivial Iconography on Roman Cineraria Carrie L. Sulosky Weaver

- 8. A Viewer Walks into a Tomb: Transformation in the Cubiculum Leonis Ethan Gannaway

- 9. Protoplasts and Prophets: The Stucco Reliefs in the Orthodox Baptistery in Ravenna Rachel Danford