eBook - ePub

Conflict and Forced Migration

Escape from Oppression and Stories of Survival, Resilience, and Hope

- 356 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Conflict and Forced Migration

Escape from Oppression and Stories of Survival, Resilience, and Hope

About this book

It is headline news that forced migration due to conflict, persecution, and violence is a world-wide human catastrophe in which over 68 million people have been displaced. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) currently reports that one in every 110 people are forced to flee their homes and that someone is forced to flee their home every two seconds. Over 40 million people are internally displaced persons, people who have fled their homes but remain in their home country. Over 25 million are refugees, people who have forsaken their homes and homeland. They have crossed their country's borders seeking safety and refuge.

This volume brings together a wide variety of contributors, from scholars and a psychiatric social worker, to former refugees who were resettled in the United States and a mural artist, to explore the current face of migration conflict. Including personal narratives, academic papers, and artistic research, this volume is split into four sections, looking at the social structure of conflict, voices of resilience, humanitarian advocacy, and art and hope. This timely collection is a relevant book for courses in sociology, anthropology, political science, and courses centering on the global problem of conflict and forced migration.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Conflict and Forced Migration by Gil Richard Musolf in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Discrimination & Race Relations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

THE SOCIAL STRUCTURE OF CONFLICT

CHAPTER 1

THE ASYLUM-SEEKING PROCESS: AN AMERICAN TRADITION

ABSTRACT

The immigration conundrum to craft policy that ensures border security and safeguards human rights is grave and complex. Individuals fleeing religious persecution made finding refuge part of our heritage since colonial times. This American tradition has enshrined our values to the world. This essay is limited to summarizing the asylum process and recent events through the summer of 2018 which affect it. Policy changes are ongoing. The asylum process is complicated by illegal immigration. The surge in migrants arriving at and/or crossing the border has led to controversial policies over the years. Unlike those who illegally cross the border and remain unknown to law enforcement, everyone who makes an affirmative asylum claim to a United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) officer, or a defensive asylum claim in immigration court, has been thoroughly vetted through identity, criminality, and terrorism background checks. Granting refuge to those fleeing persecution reaffirms the values of a country that is, as Lincoln richly stated, the last best hope of Earth. Comprehensive immigration reform is needed on many immigration issues, two of which are to ensure border security and safeguard the asylum-seeking process.

Keywords: Asylum; detention; Central America; expedited removal; parole; zero tolerance

ASYLUM SEEKERS

As a novice to the topic of the asylum process, I limit myself to an introductory essay on asylum and a summary of recent and often discussed events drawn primarily from newspaper articles and websites. I present no policy proposals, which are better left to those who are immigration and asylum scholars.

Many noncitizens or foreign nationals who arrive at ports of entry or who illegally enter the US are asylum seekers. To be granted asylum, the individual must meet the definition of a refugee, that is, a person who claims to be fleeing conflict, persecution, or violence or has a well-founded fear of persecution upon return to their country of origin. Those fears of persecution must center on race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group. According to the USCIS’s (2015) website, under US law, migrants seeking asylum are those physically present in the US. One can apply for asylum regardless of his or her current immigration status. An asylee, a person granted asylum, cannot be returned home. An asylum seeker also cannot be returned home while their claims are being examined, but, as we shall see, that process can be brief. An asylum seeker can decide to voluntarily return home. According to the American Immigration Council (AIC) (2016), unlike refugees “[t]here is no limit on the number of individuals who may be granted asylum in a given year nor are there specific categories for determining who may seek asylum.” According to AIC (2018a), between the FY 2007 and the FY 2016, annual asylum grants averaged 23,669.

During 2016, 20,455 individuals were granted asylum, including 11,729 individuals who were granted asylum affirmatively by DHS and 8,726 individuals who were granted asylum defensively by the Department of Justice (DOJ). The leading countries of nationality for persons granted either affirmative or defensive asylum were China, El Salvador and Guatemala. (Mossaad & Baugh, 2018, p. 1)

As in the case of refugees, a person granted asylum “can request derivative asylum status for spouses and unmarried children under” the age of 21 (p. 5). These family members do not have to establish persecution claims (p. 6). Whether the US will grant any asylum seeker or any family of asylum seekers asylum, is dependent on the credibility of their claims of fleeing violence and/or persecution.

AFFIRMATIVE ASYLUM

If a noncitizen is not in removal proceedings, he or she may affirmatively apply for asylum through USCIS housed within Department of Homeland Security (DHS). According to the USCIS website (2015), to affirmatively apply for asylum, the person fills out Form I-589, Application for Asylum and for Withholding of Removal. The individual must do this within one year of his or her arrival or physical presence in the US. According to AIC (2018a), “[i]n many cases, missing the one-year deadline is the sole reason the government denies an asylum application.” Unless one has “extraordinary circumstances” (USCIS, 2015), missing the one-year deadline means you are ineligible to apply for asylum. Individuals making an affirmative application are usually not detained by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) (USCIS, 2015). The individual will receive a “non-adversarial interview with an asylum officer” of the USCIS, and a supervisory officer will review the decision. There may be additional review at USCIS headquarters. According to American Immigration Council (AIC, 2018a), a decision in an affirmative asylum case could take up to four years. If the applicant is not granted asylum, then the asylum seeker will be placed in removal proceedings but can begin the defensive process of seeking asylum.

DEFENSIVE ASYLUM AND REMOVAL PROCEEDINGS

In the US, deportation or removal proceedings are adjudicated under the Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR), a branch of the Department Of Justice (DOJ). The proceeding is held in immigration courts presided over by immigration judges and is similar to a trial, but there is no jury, just a judge. Someone appearing in immigration court can be someone found to be in the country illegally, or an asylum seeker who has received a positive credible fear screening, which prevented him or her from expedited removal. The asylum seeker may be in detention or may have been released on parole or bond. However, as Eagly, Shafer, and Whalley (2018) report:

[d]ue to the remote location of detention facilities throughout the United States, immigration judges increasingly hear cases over a video connection without ever traveling to the detention center. [In fact,] an overwhelming 93 percent of family detention hearings were handled via televideo.

According to the USCIS (2015) website, if the person is appearing because of a failed affirmative asylum hearing, an immigration judge will conduct a “‘de novo’ hearing,” issuing a “decision that is independent of the decision made by USCIS.” As of May 2018, the backlog in immigration court cases was 714, 067 (TRAC, 2018). Moreover, cases are taking much longer to complete, an average of 501 days for a removal order decision and 1,064 days for a decision “granting asylum or another type of relief” (TRAC, 2018). In New Jersey and California, cases granting relief average more than 1,300 days (AIC, 2018a). Cases are different for those who have passed a credible fear hearing and those who are found in the US illegally.

The DHS will send to an individual alleged to be in the US illegally a Notice to Appear in immigration court. If the individual fails to appear in court, he or she receives an in absentia removal order. Individuals who appear will first come before an immigration judge in a “master calendar” hearing to determine what defense, if any, he or she has. According to Bray (2018a), if a noncitizen has no right, and therefore no defense to be in the US, he or she might be able to receive a discretionary grant of voluntary departure and leave the country at his or her own expense. Voluntary departure will prevent an order of removal that could make one inadmissible for a much longer time than under voluntary departure. However, failure to comply with a grant of voluntary departure has severe consequences.

If a noncitizen, for example, an asylum seeker, negotiates a successful master calendar hearing, he or she then makes an application for relief and a “merits hearing” is scheduled. According to Human Rights First (HRF) (2018), asylum seekers must make a “detailed application to the immigration court” with supporting documentation and “are only excused from providing documentation when it is unreasonable to expect them to be able to obtain it.” The immigration judge weighs many factors to assess the credibility of an asylum seeker. The asylum seeker also is cross-examined by ICE attorneys who challenge his or her credibility. Asylum seekers have the right to be represented by counsel. However, as Eagly and Shafer (2016, p. 1) state:

[b]ecause deportation is classified as a civil rather than a criminal sanction, immigrants facing removal are not afforded the constitutional protections under the Sixth Amendment that are provided to criminal defendants

such as the right to a public defender or a jury trial. According to the Practice Manual available on the EOIR’s website, “aliens in proceedings before an Immigration Court are provided with a list of free or low-cost legal service providers within the region in which the Immigration Court is located.” But because of the remote location of detention centers many asylum seekers cannot obtain counsel. Either the asylum seeker or ICE can appeal an immigration judge’s decision to the Board of Immigration Appeals. Individuals may be allowed to stay in the US while their case is under appeal. According to Wise and Petras (2018), “Board of Immigration decisions may be appealed to the federal circuit courts of appeals and, in some cases, to the Supreme Court.”

According to Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC) (2016a, 2016b, 2016c), a data research center at Syracuse University, the single most important factor in the success of an asylum petition is legal representation. Although the percentage of asylum seekers denied asylum is not as high as it was in the late 90s, when asylum denials were in the mid-70% to mid-80% range, the overall denial rate of the FY 2016 was 57%, up from the last seven years in which it varied from the high 40s to low 50s (TRAC, 2016c). As TRAC (TRAC, 2016c) states: in the FY 2016, “more than five out of every ten represented asylum seekers were successful as compared with only one out of every ten who were unrepresented.” That means 90% of unrepresented asylum seekers are denied asylum. “Currently, four out of every five asylum seekers were represented” (TRAC, 2016c). The consequences are severe for those who are unrepresented, which varies by nationality. Mexico and Central American countries had among the highest denial rates and the highest percentage of migrants who were unrepresented. From the FY 2011 to 2016, the asylum denial and unrepresented rates were as follows: Mexico 89.6% denial, 40% unrepresented; El Salvador 82.9% denial, 30.8% unrepresented; Guatemala 77.2% denial, 25.1% unrepresented; Honduras 80.3% denial, 35.6% unrepresented (TRAC, 2016c).

Eagly and Shafer (2016) have presented extensive research on the crucial consequences of legal representation. Their research is on the access to counsel for detained migrants in general. Since many asylum seekers are detained, their conclusions are applicable for asylum seekers. They document that detained individuals are more likely to be unrepresented than those not in detention, that representation rates vary by (1) court jurisdiction, (2) the size of the city, with individuals in small cities receiving less representation, and (3) the nationality of the individual. Nationality of an unauthorized migrant1 also affects detention rates. Mexicans have the highest and Chinese have the lowest detention rates. Eagly and Shafer conclude that those who obtain representation are more likely to be released from detention, to appear in court, and to seek and receive relief from removal; that is to say, those “with attorneys fare better at every stage of the court process” (p. 2).

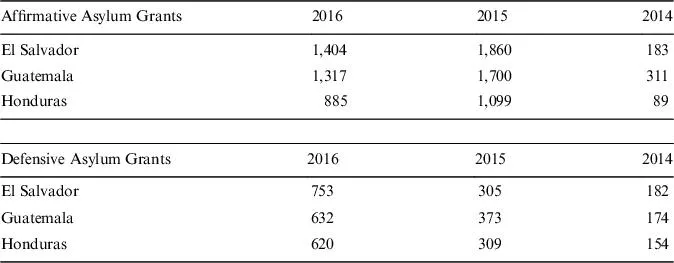

The number of individuals granted asylum is small. DHS’s Office of Immigration Statistics has provided a table with the number of affirmative and defensive asylum grants from 2014 to 2016. The table is for El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras (Mossaad & Baugh, 2018, pp. 7–8).

The total number of asylum grants from the three countries for 2014 through 2016 is 12,350. The trend is an increase in grants during this time period.

Besides representation, another variable in asylum denial rates is the immigration judge assigned to hear one’s case. TRAC’s (2016d) research demonstrated that the judge-to-judge “decision disparity” in granting asylum is extreme and has been increasing over the decades. This is especially salient when comparing the low and high denial rates of individual judges in specific immigration courts. For example, in Newark’s immigration court, there are six immigration judges. The most favorable judge (to asylum seekers) had a denial rate of 15.7% while the most unfavorable judge (to asylum seekers) had a denial rate of 98.6%. This “decision disparity” in the same court between the judge who denies the least and the judge who denies the most holds true in many immigration courts across the county. For example, in Los Angeles with 33 judges, the most favorable judge denies 21.8%, the most unfavorable denies 97.1%; in San Francisco with 17 judges, the most favorable denies 15.3%, the most unfavorable denies 97.7%. The immigration judge assigned makes an enormous difference in one’s asylum case.

EXPEDITED REMOVAL

Expedited removal is a process that affects asylum seekers arriving at a port of entry and those apprehended between ports of entry. The Supreme Court has repeatedly decided that due-process rights are unqualifiedly nonexistent for “arriving aliens” (DHS terminology) seeking to enter the US but that they do exist for unauthorized migrants already present in the US (Smith, 2018, p. 1). US courts do not grant arriving aliens either Fifth or Fourteenth Amendment constitutional rights and have consistently decided that arriving aliens “are entitled only to those procedural protections that Congress expressly authorized” (p. 1). Federal Courts and the Supreme Court have supported the “plenary power” of Congress and the “sovereign prerogative” of the State to “expel or exclude” whomever it chooses (p. 1). Court rulings have affirmed that admission to the US is a “privilege” (p. 3). Summary decisions on deportation without judicial review for arriving aliens has been held constitutional. According to Benner and Savage (2018), “the courts have [...] essentially said that Congress can decide that more limited procedures are sufficient for noncitizens at the border.” Unauthorized migrants within the US cannot be removed without due process, such as (1) right to counsel, (2) right to an administrative hearing, (3) right to administrative appeal, and (4) right to judicial review (Smith, 2018, p. 8). Unaccompanied children are not subject to expedited removal.

In 1996, the Republican Congress passed, and President Bill Clinton signed, the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act. The law instituted expedited removal, an administrative procedure to rapidly deport arriving aliens who present themselves to a Customs and Border Protection (CBP) officer at a port of entry, seaport, or airport, and who have no documents or improper documents, that is, no passport or other travel document. Currently, expedited removal also applies to unauthorized migrants app...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Introduction

- Part I The Social Structure of Conflict

- Part II Voices of Survival, Resilience, and Hope

- Part III Humanitarian Advocacy

- Part IV Art and Hope

- Index