![]()

The Raids

1939

The war was quick to come to Hull. The first siren sounded on 4 September at 03.20 hours, just hours after the declaration of war. It was a false alarm, as was the last one of the year on 21 November. It would be many months before the Luftwaffe darkened the skies above the city. However, the enemy were active against shipping along the coast and dropping mines in the Humber; one German plane crashed off Spurn Point on 21 October.

The blackout took time to adjust to and was the cause of two deaths: on 16 September William Bristow was fatally injured in a car accident and on 13 October James Watson was killed. Both deaths were directly attributed to the blackout.

A barrage balloon shown attached to a barge on the Humber.

Fire practice in Hull dock.

![]()

1940

Two weeks into the New Year and Hull suffered another civilian death from the blackout: John Corpe was drowned in Hull Dock on 14 January. Although there were no casualties from bombing, it did not mean that the skies around Hull and the coast were clear of the enemy. There were no raids but enemy intruders often overflew the area or dropped mines in the Humber or along the East Yorkshire coast.

The first large raid of the year began on 19/20 June around 22.50 hours and lasted until 03.56 hours. An incendiary dropped in a field at Marfleet and an hour later incendiaries were dropped on Buckingham Street, Victor Street and the immediate neighbourhood; the bombing that night over east Hull was widespread.

A direct hit on the National Provincial Bank on Holderness Road bank in June 1940 destroyed the building but the two safes were undamaged.

During the raid, bombs were also dropped on Jalland Street, Jesmond Gardens, Rowlands Terrace, Severn Street, Alpha Terrace and Cornwall Street. Fortunately most residents in the affected area were in communal or domestic shelters and there were no reported casualties.

Fifty-four incendiary and three high explosive bombs were dropped near Marfleet Lane School. Bombs dropped near Chapman Street Bridge damaged the parapet and an incendiary on the road down Buckingham Street was left to burn out. Other bombs fell in Buckingham Street, Villa Terrace, on Barnsley Street road surface and in Johnson’s coal yard on Barnsley Street where a stable and telephone kiosk were burned out, the horses being saved. Mersey Street was the worst hit, but the resulting damage sustained was mostly to roofs and ceilings. Not all the bombs exploded.

Buckingham Street after the raid of 19/20 June 1940.

There were a few high explosive bombs, but little damage was done, at any rate compared with what was to come. Charles Ablett, at 12 Harold’s Avenue, had a lucky escape that night. He was in his bedroom when an incendiary struck the wall and part of the bomb hit him on the head. He suffered only minor injuries and the bomb failed to ignite.

The only important target hit was the Damson Lane railway crossing, unless setting fire to the ceiling, skirting boards and drapes in the bedroom of 128 Severn Street was the main objective.

A week later the bombers arrived over Hull just after midnight on 26 June. The target was again east Hull: the Holderness Road area. This early-morning raid caused extensive damage to housing on all sides of East Park: Summergangs Road, Kelvin Street, Westcott Street, Lee Street, Faraday Street, Laburnum Avenue, James Reckitt Avenue, Chamberlain Road, Lodge Street and the playing fields. Although there was a smell of coal gas and some trolley wires were down, nothing of military importance was hit and there were no casualties.

Holderness Road in June 1940, showing the effects of a minor raid on the city.

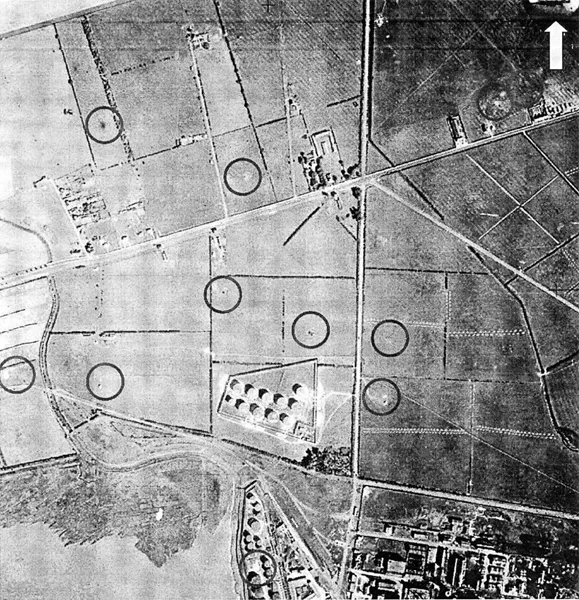

Just a few days later on 1 July, Saltend suffered the first daylight raid on British territory when sixteen high explosive bombs were dropped (800kg in total). The firing of the AA batteries was the first intimation that Hull might be under attack. However, it was a lone aircraft, a Heinkel 111-4 bomber, on a ‘nuisance raid’. After flying over the city, firing unsuccessfully at barrage balloons, it dropped bombs on Saltend refinery, most of which landed outside the depot. Shrapnel punctured a storage tank and the leaking fuel caught fire, threatening the other tanks. Fortunately the refinery had its own fire station which was quick to control the blaze. A major explosion was prevented by the bravery of a number of men who were awarded the George Medal for their actions. Jack Owen and George Sewel kept hosing down the red-hot top of a tank while waiting for foam to arrive, during which time 2,000 tons of fuel was extracted. Three other men, George Howe, William Sigsworth and Clifford Turner, were also awarded the George Medal for their actions during the fire. It was a scenario that they had been trained for. The complete story is recorded in the official account of the Fire Services during the war.

The bomber did not return to its base at Wittmundhaven. It was shot down by Spitfires of 616 Squadron and crashed off Spurn Head. The crew were picked up by HMS Black Swan and became PoWs.

After nearly a month of peace, the Luftwaffe returned on 30 July. The raid was over in just 20 minutes with the sirens sounding at 00.30 hours and the All-Clear at 00.50 hours. Just two 50kg high explosive bombs were dropped. Mallory’s shop in Porter Street was demolished and two nearby public houses and other dwellings were damaged by one bomb. The second bomb, falling in Passage Street, damaged flats, housing and demolished an unoccupied shop. Only one incident resulted from this raid: a 13-year-old girl was seriously injured by shrapnel in St. Lukes Street.

The next raid hardly counted as such. On 15 August an enemy plane fired cannon shells, presumably at barrage balloons, three of which were damaged and had to be replaced. Six unexploded cannon shells were found at the site and handed to the Bomb Disposal Service. The firing caused slight residential damage in Marfleet Lane and Hopkins Street. Fortunately for Hull it was not the target: the raid had the purpose of destroying Driffield as an air base with a subsidiary attack on Bridlington.

Aerial photo of where bombs fell during the raid on Saltend on 1 July 1940.

The next day Hull was again lucky: the single plane raid did not materialise. It was shot down by AA fire from Immingham.

On 18 August German planes dropped bombs on Central Street area on the River Hull; three air raid shelters were hit. During the night the casualty services dealt with 53 people; there were 20 dead, one of whom was Annie Brown of 1 Cherry Tree Avenue. This was part of an attack on Bridlington. Although enemy bombers were plotted on many occasions near Hull, there were no more raids for a week.

A bigger raid followed on 24/25 August when eight 250kg high explosive bombs were dropped. Two bombs demolished three houses in Northumberland Villas, further bombs landed on Carlton Street and Eastbourne Street. In total six homes were destroyed, three severely damaged and over eighty badly damaged. A bomb in Eastbourne Street left a crater 18 feet in diameter and 8 feet deep and wrecked 12 houses. Four bombs dropped on Rustenburg Street (four people killed) and Morrill Street produced whistling sounds; one creating a four feet deep crater that was over 100 feet in diameter. Just four bombs demolished 3 shops and 25 homes, badly damaged 11 shops and 66 homes, and slightly damaged 63 more. An Anderson shelter was damaged in Rustenburg Street. In Wharram Street and Northumberland Villas two bombs wrecked 20 houses and broke windows in another 695. The streets affected were: Barmston Street, Buckingham Street, Castle Street, Chanterlands Avenue, Eastbourne Street, Holderness Road, Holland Street, Morrill Street, National Avenue, Northumberland Avenue, Rensburg Street, Rustenburg Street, Severn Street and Wharram Street.

It was a busy night for organisations like the WVS and reception centres: the bombing made 240 people homeless. Similarly, the medical services were kept busy with over 80 needing treatment: 6 people were killed, 10 were seriously injured and a further 55 received treatment for less serious wounds and injuries. Those killed during the raid were: Betty (15) and Doreen Bolton (6) of 47 Rustenburg Street; Dorothy Amelia (22) and Frederick Scott (25) of 136 Rustenburg Street; William L’estrange Cromer Smith (34) of 13 Maud Parade, Carlton Street and Cyril Ernest Wade (35) of 4 Maud Parade, Carlton Street.

As part of a bigger series of raids across the north-east, Hull was hit on the night of 25/26 August. A large number of incendiary bombs were dropped on Alexandra and Victoria docks, causing virtually no damage and resulting in no casualties.

Just over 24 hours later, on 28 August, the raiders returned. In a minor attack, 7 or more 50kg high explosive bombs were dropped on Drypool Goods Yard and in the garden of a maternity hospital. The damage was light: a house had to be demolished, there was minor damage to the goods yard and Seward Street goods station, and around 200 other buildings were damaged. The only casualty was John Haughton: he was treated for shock.

Not all bombs exploded, for safety this meant evacuating the area. During the raid on 30/31 August nine 50kg and a single 250kg high explosive bombs were dropped. A single dud among the bombs that straddled the area resulted in the whole of Bellamy Street and part of Williamson Street being cleared and the residents moved to other accommodation. Bombs that did explode caused damage in Williamson Street, the permanent way of the LNER Victoria Dock, and East Wharf of Victoria Dock near the timber storage areas. The Albion Hotel was badly damaged and the presence of rubble and a broken water main blocked Hedon Road for some time. Alice Carter of 6 Williamson Terrace was seriously injured. The only fatal casualty was Annie Beasty aged 47.

Not all the bombs intended for Hull landed on the city. On the night of 2/3 September, during an attack on King George Dock, twelve high explosive bombs landed in the river between Corporation Road and Alexandra Dock lock-pit, approximately 800 yards from shore. However, unlike the previous raid which hit the city and caused no injuries, in this raid a member of the crew of an RAF barge in the river sustained a serious injury. He was hit in the right lung by a piece of shrapnel and also in the right thigh. AC1 Bryan made a successful recovery. Slight damage was done to the barge on which four other RAF men were stationed.

Even when quite large numbers of bombs were dropped, sometimes only slight damage resulted. During the raid on the night of 4/5 September, thirty-six incendiaries were dropped on Dalton Street, Tower Street, Cottingham Road, Chanterlands Avenue, Park Avenue and Clough Road; the resulting fires were put out immediately with little damage. One youth was slightly injured putting out one of the fires.

On the night of 5/6 September the Luftwaffe dropped incendiary bombs on the James Reckitt Avenue and Chamberlain Road area. Most landed in fields: no fires were started, or casualties reported. However, the intruder did manage to slightly damage two stationary barrage balloons with machine-gun fire.

It was as if the Luftwaffe was not really trying during September. During the next two raids, on 10/11 and 23/24 September, incendiary bombs were dropped on the Telford, Steynburg and Margaret Street area and on the Maybury Road and Bellfield Avenue area. The bombs dropped on 10/11 September started a few quickly-extinguished fires; no damage or casualties were reported. All of the bombs on the night of 23/24 September fell on open ground and were quickly put out with no resulting damage.

The absence of the Luftwaffe over the city did not mean they had gone away. During the period of calm before the next raid on Hull, there were reports of planes laying mines off the Humber mouth.

After a break of nearly three weeks, the raiders returned on 12/13 October bombing Stoneferry, Kathleen Road and the Maxwell and Woodhall Street areas. Damage to domestic and industrial buildings was light, even though the enemy dropped both high explosive and incendiary devices. A single-storey warehouse at the Naval Depot in Sculcoates was badly damaged and bedding was destroyed. On Kathleen Road, twenty houses and a shop were damaged by one bomb, and in Maxwell Street three bombs demolished a warehouse and badly damaged two others. During the raid eight people were seriously injured and two killed. They were out walking together during the raid and were caught in the blast of a bomb: Marion Hairsine (22) of 4 Easton Avenue died immediately and Doreen Walker (17) of 1 Kathleen Road succumbed to her injuries later.

The next raid was the first use of a new weapon, one already known to British Intelligence: the 1,000kg parachute mine. Incredibly, two of the mines were dropped on the night of 21/22 October before the warning was sounded. The one in the Sutton and Silverdale Roads and Bellfield Avenue areas caused extensive damage to hundreds of houses, with windows broken up to a mile away. The explosion and blast caused many casualties, of which six were seriously injured and three fatal, one of whom was 30-year-old Ivy Freeman. The strength of the blast from this new bomb is shown by the following episode, which also shows just how lucky some people were. A man getting dressed was lifted to the ceiling of the bedroom, and then found he was on his b...