eBook - ePub

Introduction to One Health

An Interdisciplinary Approach to Planetary Health

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Introduction to One Health

An Interdisciplinary Approach to Planetary Health

About this book

Introduction to One Health: An Interdisciplinary Approach to Planetary Health offers an accessible, readable introduction to the burgeoning field of One Health.

- Provides a thorough introduction to the who, what, where, when, why, and how of One Health

- Presents an overview of the One Health movement viewed through the perspective of different disciplines

- Encompasses disease ecology, conservation, and veterinary and human medicine

- Includes interviews from persons across disciplines important for the success of One Health

- Includes case studies in each chapter to demonstrate real-world applications

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Introduction to One Health by Sharon L. Deem,Kelly E. Lane-deGraaf,Elizabeth A. Rayhel in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Veterinary Medicine. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

An Introduction and Impetus for One Health

1

Why One Health?

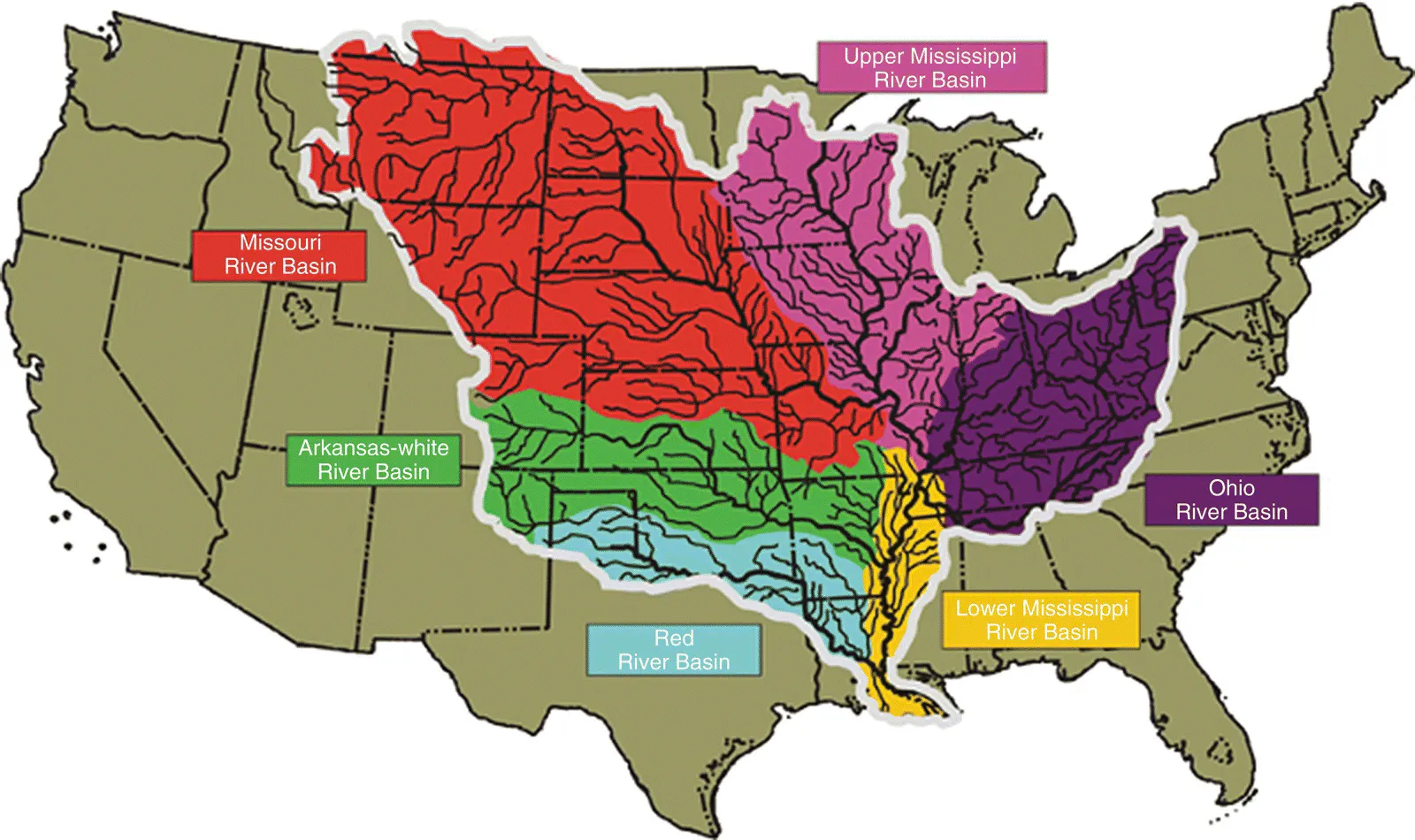

The Mississippi River today is the source of economic strength and cultural movement throughout the USA. The Mississippi reaches more than 2300 miles from Lake Itaska in northwestern Minnesota to the Gulf of Mexico (Figure 1.1). The fourth largest watershed on the planet, it covers 32 states and 40% of the landmass of the USA and reaches from Appalachia to the Rocky Mountains. Pre‐dating the European expansion into the Americas, Native American cultures thrived along the Mississippi River Basin. The Ojibwe, the Kickapoo, the Potawatomi, the Chickasaw, the Cahokia, the Choctaw, the Tunica, the Natchez, and many more peoples lived and flourished along the Mississippi River. Culturally diverse and rich in tradition, the peoples of the Mississippi River basin used and respected animals and the environment throughout their traditions. Focused on fishing and hunting, small‐scale farming, and foraging, the traditions of the peoples of the Mississippi River are as varied as the people themselves, but importantly, these traditions shared a focus on maintaining a balance between humans, animals, and the environment. The culturally diverse native peoples of the Mississippi River region could truly be considered the first One Health practitioners of the region.

Figure 1.1 Mississippi River watershed.

In 1539, Hernando de Soto of Spain became the first European to witness the majesty and power of the Mississippi River. In his explorations and quest for gold, de Soto and his men frequently interacted with native peoples. The Spaniards, from their first landfall, exploited native peoples. Language and culture differences, not surprisingly, emerged frequently. de Soto traveled with one translator, who spoke the language of only one tribe. As a result, skirmishes between the Spaniards and the native peoples often broke out while traveling. When the army with which de Soto traveled, numbering approximately 620, encountered a local community, they demanded use of the food stores, preferring this to hunting. As a result, the Spaniards consumed nearly a year’s worth of food in only a few days in each community they encountered, with devastating impacts on the survival of these local communities. de Soto and his men also routinely enslaved men, women, and children, demanding individuals carry their equipment and gear, care for their horses, provide cooked food, lodging, and sexual services. Native peoples who resisted were frequently raped, tortured, had their homes and crops burned, and/or were killed. The violence of the initial European arrivals to the Mississippi region resulted in the murder of an uncountable number of native peoples.

The devastation of the communities of Native Americans is not the only devastation de Soto and his men wrought on the Mississippi Basin. The Spaniards were exploring to claim the land for Spain and loot the region of its gold, silver, and other precious metals. In addition to men, de Soto brought with him 220 horses and 100 pigs. The movement of this army of people and animals from present day Florida west through Louisiana, north through Arkansas and into Missouri, and then south to Texas left in its trail a swath of deforestation, biodiversity loss, and pollution – all One Health threats. For example, while the Spaniards exploited Native American paths for travel as much as possible, they also carved many new paths through the forests and prairies that they crossed. The livestock brought along also created significant problems for the landscape. Feeding these animals created an additional burden for the land, taxing the ecosystems as the traveling herd of between 300 and 1000 domesticated animals trampled vast swathes of pristine forest and prairie vegetation. Rats and other stowaways from their ships would, in time, become invasive and drive their own ecological catastrophes. de Soto’s herd of pigs, which grew from 100 to over 900 by 1542, brought its own unique environmental and ecological threats.

The normal behaviors of pigs – rooting for tubers, wallowing in mud, and trampling vegetation – wreaked havoc on native plant life and, importantly, their feces introduced an entire suite of novel pathogens to an area, contaminating local water supplies as they defecated across the south. An often overlooked consequence of early western explorations was the introduction of lead shot into the Americas; with this, de Soto and his army slaughtered countless native animal species and introduced the potential for lead pollution into the Mississippi River basin.

In what could be considered one of the earliest intercultural One Health threats, the greatest devastation brought by de Soto and his men was not the rape and pillaging of the land and local communities but the introduction of novel infectious diseases into naïve populations. In the wake of de Soto’s army, smallpox and measles spread rapidly through the diverse tribes of native peoples of the Mississippi Basin, who were exposed to these pathogens as de Soto and his men traveled through their communities. Smallpox alone killed an estimated 95% of the people with whom the Spaniards came into contact, effectively eliminating entire communities in their wake. This drastically altered the make‐up of the Native American landscape well before the French and English returned some 100 years later. de Soto did not survive his expedition, dying on the banks of the Mississippi River of a fever without finding a single piece of gold or silver. More than half of his men perished along the way as well.

Fast forward 150 years to 1682, when, after exploring its reaches and seizing upon the economic and strategic benefit of the Mississippi River system, René‐Robert Cavelier, sieur de la Salle claimed the river for France. The southern stretches of the Mississippi Basin briefly fell under the control of the Spanish in 1769; in 1803, the USA, not even 30 years old, purchased the entirety of the Mississippi River watershed as a part of the Louisiana Purchase. When in May of 1804, William Clark, Meriwether Lewis, and 31 others set forth from St. Louis, MO, to find a Northwest Passage, a water route to the Pacific, they were tasked with acting as cartographers, naturalists, and cultural emissaries for the young country. Thomas Jefferson, who commissioned the expedition in 1803, believed that the most critical role for the commissioned explorers was to act as diplomats for the nation among the several Native American tribes the group would encounter. The Corps of Discovery, as the expedition came to be called, ultimately made contact with 55 independent groups of Native Americans and First Peoples, frequently trading for food and medical supplies as well as befriending many tribes people.

Lewis and Clark traversed nearly 8000 miles. Their expedition is touted by many as a model of inclusion – a black man, York, and a Shoshone woman, Sacagawea, were essential members after all. However, their inclusion hints at the exploitative nature of the Corps itself. York was a master hunter, bringing in a large portion of the game that fed the Corps throughout their journey, and acted frequently as the expedition’s most stalwart caregiver, providing care to ill expedition members. Still, York was Clark’s slave. He was not a paid member of the Corps of Discovery, despite his critical role in its success. Sacagawea was kidnapped as a teen by the Hidatsa and then sold to her “husband” Charbonneau. As property, neither York nor Sacagawea could refuse participation in the 8000 mile journey. Still, Sacagawea, like York, played a vital role in the expedition, acting as translator and helping with the group’s welcome by many Native American peoples.

In all, the Lewis and Clark expedition, while fondly remembered today, was considered at the time as something of a failure. They discovered no Northwest Passage; the northern route chosen by the group was arduous and challenging in a way that the southern route across the Rockies is not and so was not used by later settlers. They mapped lands, documented plants and animals, and improved diplomatic relations with Native peoples, but they also opened the country to western occupation that drastically altered the landscape, replaced the diversity of plants and animals with corn and cows, each with long‐term ecological consequences, and ravaged Native American communities through broken treaties, forced migrations, and massacres.

Lewis and Clark’s expedition had two additional repercussions in the US West: the spread of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and widespread mercury contamination to the environment. STDs were not introduced to Native Americans by the Corps of Discovery; French and Canadian fur‐trappers accomplished this. However, STDs spread through the Corps rapidly. As the men traveled west and as they encountered local tribes, it was common for members to trade goods for sex, and frequently, wives of chiefs of several High Plains tribes were shared with expedition members in order to benefit from the men’s spiritual power. The result of this was the spread of STDs across the northwest, as the Corps of Discovery shared infections between peoples who would never have otherwise come into contact with each other. At the time, there were few treatments for STDs available, with modern medicine of the day advocating a strong course of mercury pills and bloodletting. As a result of the rampant STDs, members of the Corps of Discovery were also all exposed to toxic levels of mercury. Additionally, heavy use of laxatives, brought on by the lack of plant materials and over‐consumption of meats in their diets causing chronic constipation, further increased mercury levels amo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Part I: An Introduction and Impetus for One Health

- Part II: The One Health Triad

- Part III: Practitioners and Their Tools

- Part IV: How to Start a Movement

- Part V: The Humanities of One Health

- Part VI: Where Do We Go From Here?

- Glossary

- Index

- End User License Agreement