eBook - ePub

Urban Sustainability and River Restoration

Green and Blue Infrastructure

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Urban Sustainability and River Restoration

Green and Blue Infrastructure

About this book

Urban Sustainability and River Restoration: Green and Blue Infrastructure considers the integration of green and blue infrastructure in cities as a strategy useful for acting on causes and effects of environmental and ecological issues. River restoration projects are unique opportunities for sustainable development and smart growth of communities, providing multiple environmental, economic, and social benefits.This book analyzes initiatives and actions carried out and developed to improve environmental conditions in cities and better understand the environmental impact of (and in) dense urban areas in the United States and in Europe.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Urban Sustainability and River Restoration by Katia Perini,Paola Sabbion,Paola Sabbion in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Sustainable Development. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part B

Strategies and Techniques

Chapter 6

Green and Blue Infrastructure – Vegetated Systems

Paola Sabbion

6.1 The role of GBI vegetation

Vegetation plays a key role in the implementation of green and blue infrastructure (GBI) because it provides a wide range of ecosystem services (as described in Chapters 1–5). GBI involves multiple environmental benefits and curbs climate change (through energy use reduction; climatic modification; temperature decrease; shading; evapotranspiration; wind speed modification). It also contributes to air quality improvement (emission avoidance; carbon sequestration; pollutant removal); water cycle re‐naturalisation (canopy interception; flow control; flood reduction; soil infiltration and storage; water quality improvement); soil improvement (permeability increase; soil stabilisation; nutrient cycling; waste decomposition); biodiversity enhancement (habitat and corridor creation; species diversity fostering); food production (productive agricultural land and urban agriculture development); other economic benefits (property value rise; ecosystem service value; commercial vitality); social benefits (human health and well‐being improvement; physical, social and psychological side‐effects; community and cultural vitality; visual and aesthetic beautification.

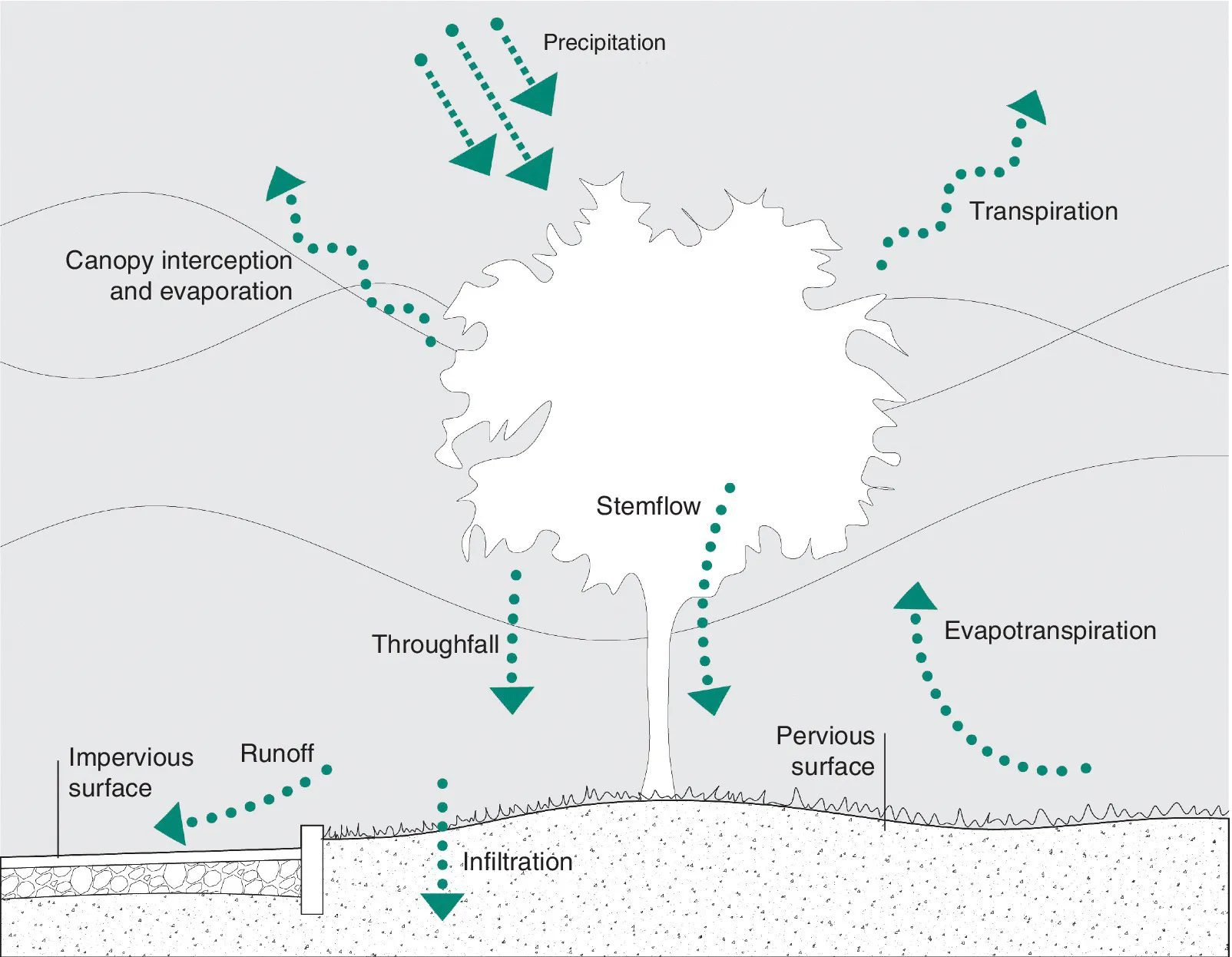

GBI proves to be so effective also thanks to vegetation performing a number of hydrologic functions within the natural water cycle. For this reason, vegetation has become an important component of the Water Sensitive Urban Design (WSUD) strategies in Australia and of the Best Management Practices (BMPs) and Low Impact Development (LID) in the United States. These systems and related guidelines seek to replicate the natural water cycle in urban areas (see also Chapters 7 and 12). Hydrologic functions provided by trees and plants are canopy interception, stemflow, soil infiltration, evapotranspiration, hydraulic lift/redistribution, groundwater recharge, and conveyance of large storms (Figure 6.1). Water quality can similarly be improved by natural systems filtering pollutants (Benedict and McMahon, 2001). Vegetation plays an important role with regard to biofiltration, as it enhances the capacity of soils to remove pollutants through a combination of biological, chemical, and physical processes (Riser‐Roberts, 1998; Pilon‐Smits, 2005). All these benefits can restore the ecological condition of urban rivers reduce overflow and flood risk, and increase water quality to enhance and protect biodiversity.

Selection of vegetation employed for GBI is based on the appropriateness of a plant according to the site conditions and programmatic requirements (its specific horticultural needs, its role on the site and in a larger plant community). A viable selection considers on‐site climate, soils and hydric conditions as well as potential interactions between species, and future maintenance needs. For example, on a site that is likely to accumulate excess water it is necessary to identify and grow plants coming mostly from wetland communities. If the soil is contaminated by organic and inorganic pollutants, species to address phytoremediation should be selected (Calkins, 2011).

Figure 6.1 Role of Vegetation in the Natural Hydrologic Cycle.

6.2 Multifunctional ecological systems in urban areas

The ecological structure of landscapes, according to ecologists, consists of matrix patches (the dominant feature) and relevant connecting corridors. Large patches should be preserved in urban areas to increase biodiversity and form new connections between the remnant patches and ecological/habitat corridors (Barnes, 1999). Corridors are often termed as habitat corridors, wildlife corridors, or ecological structures. Planning habitat corridors, linking patches with surrounding environments, can contribute to increase biodiversity and ecosystem health (see Chapter 5). Developing ecological networks revolves around a set of ecosystems, linked in a spatially coherent interconnection through the flows of organisms, and interacting with the landscape matrix in which they are embedded. This is a means of alleviating the ecological impacts of habitat fragmentation. For this reason, biodiversity conservation strategies are an integral part of sustainable landscape promotion (Opdam et al., 2006). The elements and components of green infrastructure allow the improvement of ecosystem health, defined as the occurrence of normal ecosystem processes and functions, free from distress and degradation, maintaining organisation and autonomy over time and resilience to stress (Lu and Li, 2003). Heterogeneous habitats, which are characterised by species diversity and relative species and genes differentiation, are considered more resilient than homogeneous habitats (Loreau et al., 2002). Heterogeneous habitats can influence the health of urban ecosystems by contributing to their resilience, organisation, and vigour (Tzoulas et al., 2007). Biodiversity and ecosystem health are the key elements for the implementation of ecosystem services at every scale (Vergnes et al., 2013).

GBI may provide the physical basis for ecological networks. Ecological and habitat corridors, in particular, are considered as landscape elements, which can counteract the negative effects of habitat fragmentation. Many countries have developed their own legal definitions of corridor, emphasising different objectives and approaches to biodiversity conservation (Jongman et al., 2004) and identifying landscape management policies to protect and develop corridors within green frameworks from local to regional scales (Bryant, 2006; EEA, 2012; Jongman et al., 2004; Vergnes et al., 2013).

Ecological corridors usually have a linear structure – as they can be found on linear pieces of land, which are different from the surrounded matrix (Forman, 1995) – where plants and animals can travel from one area to another, increasing the movement of organisms among patches in fragmented landscapes or among landscape elements in a mosaic of habitat types (Hess and Fischer, 2001; Bailey, 2007; Gilbert‐Norton et al., 2010; Vergnes et al., 2013; Figure 6.2). The restoration of natural riparian systems and wetlands found in river and stream corridors is one of the best practices t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- About the Authors

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword

- Part A: Definition of the Issue

- Part B: Strategies and Techniques

- Part C: Opportunities and Policies

- Index

- End User License Agreement