- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

Big Data and Analytics for Insurers is the industry-specific guide to creating operational effectiveness, managing risk, improving financials, and retaining customers. Written from a non-IT perspective, this book focusses less on the architecture and technical details, instead providing practical guidance on translating analytics into target delivery. The discussion examines implementation, interpretation, and application to show you what Big Data can do for your business, with insights and examples targeted specifically to the insurance industry. From fraud analytics in claims management, to customer analytics, to risk analytics in Solvency 2, comprehensive coverage presented in accessible language makes this guide an invaluable resource for any insurance professional.

The insurance industry is heavily dependent on data, and the advent of Big Data and analytics represents a major advance with tremendous potential – yet clear, practical advice on the business side of analytics is lacking. This book fills the void with concrete information on using Big Data in the context of day-to-day insurance operations and strategy.

- Understand what Big Data is and what it can do

- Delve into Big Data's specific impact on the insurance industry

- Learn how advanced analytics can revolutionise the industry

- Bring Big Data out of IT and into strategy, management, marketing, and more

Big Data and analytics is changing business – but how? The majority of Big Data guides discuss data collection, database administration, advanced analytics, and the power of Big Data – but what do you actually do with it? Big Data and Analytics for Insurers answers your questions in real, everyday business terms, tailored specifically to the insurance industry's unique needs, challenges, and targets.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction – The New ‘Real Business’

‘The real business of insurance is the mitigation of countless misfortunes.’—Joseph George Robins (1856–1927)

1.1 On the Point of Transformation

1.1.1 Big Data Defined by Its Characteristics

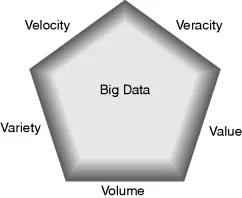

- Volume – the sheer amount of structured and unstructured data that is available. There are differing opinions as to how much data is being created on a daily basis, usually measured in petabytes or gigabytes, one suggestion being that 2.5 billion gigabytes of information is created daily.2 (A ‘byte’ is the smallest component of computer memory which represents a single letter or number. A petabyte is 1015 bytes. A ‘gigabyte’ is one-thousand million bytes or 1020 bytes.) But what does this mean? In 2010 the outgoing CEO of Google, Eric Schmidt, said that the same amount of information – 5 gigabytes – is created in 48 hours as had existed from ‘the birth of the world to 2003.’ For many it is easier to think in terms of numbers of filing cabinets and whether they might reach the moon or beyond but such comparisons are superfluous. Others suggest that it is the equivalent of the entire contents of the British Library being created every day. It is also tempting to try and put this into an insurance context. In 2012 the UK insurance industry created almost 90 million policies, which conservatively equates to somewhere around 900 million pages of policy documentation. The 14m books (at say 300 pages apiece) in the British Library equate to about 4.2 billion pages or equivalent to around five years of annual UK policy documentation. In other words, it would take insurers five years to fill the equivalent of the British Library with policy documents (assuming they wanted to). But let's not play games – it is sufficient to acknowledge that the amount of data and information now available to us is at an unprecedented level.Perhaps because of the enormity of scale, we seek to define Big Data not just by its size but by its characteristics.

- Velocity – the speed at which the data comes to us, especially in terms of live streamed data. We also describe this as ‘data in motion’ as opposed to stable, structured data which might sit in a data warehouse (which is not, as some might think, a physical building, but rather a repository of information that is designed for query and analysis rather than for transaction processing). ‘Streamed data’ presents a good example of data in motion in that it comes to us through the internet by way of movies and TV. The speed is not one which is measured in linear terms but rather in bytes per second. It is governed not only by the ability of the source of the data to transmit the information but the ability of the receiver to ‘absorb’ it. Increasingly the technical challenge is not so much that of creating appropriate bandwidth to support high speed transmittal but rather the ability of the system to manage the security of the information.In an insurance context, perhaps the most obvious example is the whole issue of telematics information, which flows from mobile devices not only at the speed of technology but also at the speed of the vehicle (and driver) involved.

- Variety – Big data comes to the user from many sources and therefore in many forms – a combination of structured, semi-structured and unstructured. Semi-structured data presents problems as it is seldom consistent. Unstructured data (for example plain text or voice) has no structure whatsoever. In recent years an increasing amount of data is unstructured, perhaps as much as 80%. It is suggested that the winners of the future will be those organizations which can obtain insight and therefore extract value from the unstructured information.In an insurance context this might comprise data which is based on weather, location, sensors, and also structured data from within the insurer itself – all ‘mashed’ together to provide new and compelling insights. One of the clearer examples of this is in the case of catastrophe modeling where insurers have the potential capability to combine policy data, policyholder input (from social media), weather, voice analysis from contact centers, and perhaps ot...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- About the Author

- Chapter 1: Introduction – The New ‘Real Business’

- Chapter 2: Analytics and the Office of Finance

- Chapter 3: Managing Financial Risk Across the Insurance Enterprise

- Chapter 4: Underwriting

- Chapter 5: Claims and the ‘Moment of Truth’

- Chapter 6: Analytics and Marketing

- Chapter 7: Property Insurance

- Chapter 8: Liability Insurance and Analytics

- Chapter 9: Life and Pensions

- Chapter 10: The Importance of Location

- Chapter 11: Analytics and Insurance People

- Chapter 12: Implementation

- Chapter 13: Visions of the Future?

- Chapter 14: Conclusions and Reflections

- Appendix A: Recommended Reading

- Appendix B: Data Summary of Expectancy of Reaching 100

- Appendix C: Implementation Flowcharts

- Appendix D: Suggested Insurance Websites

- Appendix E: Professional Insurance Organizations

- Index

- End User License Agreement