eBook - ePub

The Biology of Parasites

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This heavily illustrated text teaches parasitology from a biological perspective. It combines classical descriptive biology of parasites with modern cell and molecular biology approaches, and also addresses parasite evolution and ecology.

Parasites found in mammals, non-mammalian vertebrates, and invertebrates are systematically treated, incorporating the latest knowledge about their cell and molecular biology. In doing so, it greatly extends classical parasitology textbooks and prepares the reader for a career in basic and applied parasitology.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Biology of Parasites by Richard Lucius,Brigitte Loos-Frank,Richard P. Lane,Robert Poulin,Craig Roberts,Richard K. Grencis, Ron Shankland, Renate FitzRoy, Ron Shankland,Renate FitzRoy in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Neuroscience. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

General Aspects of Parasite Biology

Richard Lucius and Robert Poulin

- 1.1 Introduction to Parasitology and Its Terminology

- 1.1.1 Parasites

- 1.1.2 Types of Interactions Between Different Species

- 1.1.2.1 Mutualistic Relationships

- 1.1.2.2 Antagonistic Relationships

- 1.1.3 Different Forms of Parasitism

- 1.1.4 Parasites and Hosts

- 1.1.5 Modes of Transmission

- Further Reading

- 1.2 What Is Unique About Parasites?

- 1.2.1 A Very Peculiar Habitat: The Host

- 1.2.2 Specific Morphological and Physiological Adaptations

- 1.2.3 Flexible Strategies of Reproduction

- Further Reading

- 1.3 The Impact of Parasites on Host Individuals and Host Populations

- Further Reading

- 1.4 Parasite–Host Coevolution

- 1.4.1 Main Features of Coevolution

- 1.4.2 Role of Alleles in Coevolution

- 1.4.3 Rareness Is an Advantage

- 1.4.4 Malaria as an Example of Coevolution

- Further Reading

- 1.5 Influence of Parasites on Mate Choice

- Further Reading

- 1.6 Immunobiology of Parasites

- 1.6.1 Defense Mechanisms of Hosts

- 1.6.1.1 Innate Immune Responses (Innate Immunity)

- 1.6.1.2 Acquired Immune Responses (Adaptive Immunity)

- 1.6.1.3 Scenarios of Defense Reactions Against Parasites

- 1.6.1.4 Immunopathology

- 1.6.2 Immune Evasion

- 1.6.3 Parasites as Opportunistic Pathogens

- 1.6.4 Hygiene Hypothesis: Do Parasites Have a Good Side?

- 1.6.1 Defense Mechanisms of Hosts

- Further Reading

- 1.7 How Parasites Alter Their Hosts

- 1.7.1 Alterations of Host Cells

- 1.7.2 Intrusion into the Hormonal System of the Host

- 1.7.3 Changing the Behavior of Hosts

- 1.7.3.1 Increase in the Transmission of Parasites by Bloodsucking Vectors

- 1.7.3.2 Increase in Transmission Through the Food Chain

- 1.7.3.3 Introduction into the Food Chain

- 1.7.3.4 Changes in Habitat Preference

- Further Reading

1.1 Introduction to Parasitology and Its Terminology

1.1.1 Parasites

Parasites are organisms which live in or on another organism, drawing sustenance from the host and causing it harm. These include animals, plants, fungi, bacteria, and viruses, which live as host-dependent guests. Parasitism is one of the most successful and widespread ways of life. Some authors estimate that more than 50% of all eukaryotic organisms are parasitic, or have at least one parasitic phase during their life cycle. There is no complete biodiversity inventory to verify this assumption; it does stand to reason, however, given the fact that parasites live in or on almost every multicellular animal, and many host species are infected with several parasite species specifically adapted to them. Some of the most important human parasites are listed in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1 Occurrence and distribution of the more common human parasites

| Parasite | Infected people (in millions) | Distribution |

| Giardia lamblia | >200 | Worldwide |

| Trichomonas vaginalis | 173 | Worldwide |

| Entamoeba histolytica | 500* | Worldwide in warm climates |

| Trypanosoma brucei | 0.01 | Sub-Saharan Africa (“Tsetse Belt”) |

| Trypanosoma cruzi | 7 | Central and South America |

| Leishmania spp. | 2 | Near + Middle East, Asia, Africa, Central and South America |

| Toxoplasma gondii | 1500 | Worldwide |

| Plasmodium spp. | >200 | Africa, Asia, Central and South America |

| Paragonimus sp. | 20 | Africa, Asia, South America |

| Schistosoma sp. | >200 | Asia, Africa, South America |

| Hymenolepis nana | 75 | worldwide |

| Taenia saginata | 77 | Worldwide |

| Trichuris trichiura | 902 | Worldwide in warm climates |

| Strongyloides stercoralis | 70 | Worldwide |

| Enterobius vermicularis | 200 | Worldwide |

| Ascaris lumbricoides | 1273 | Worldwide |

| Ancylostoma duodenale and Necator americanus | 900 | Worldwide in warm climates |

| Onchocerca volvulus | 17 | Sub-Saharan Africa, Central and South America |

| Wuchereria bancrofti | 107 | Worldwide in the tropics |

Source: Compiled from various authors.

*many of those asymptomtic or infected with the morphologically identical Entamoeba dispar.

The term parasite originated in Ancient Greece. It is derived from the Greek word “parasitos” (Greek pará = on, at, beside; sítos = food). The name parasite was first used to describe the officials who participated in sacrificial meals on behalf of the general public and wined and dined at public expense. It was later applied to minions who ingratiated themselves with the rich, paying them compliments and practicing buffoonery to gain entry to banquets where they would snatch some food.

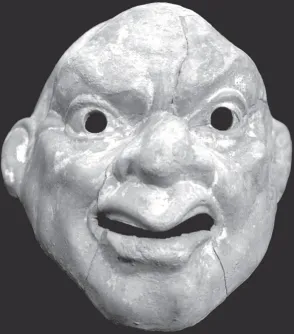

The result was a character figure, a type of Harlequin, who had a fixed role to play in the Greek comedy of classical antiquity (Figure 1.1). Later, “parasitus” also became an integral part of social life in Roman antiquity. It also reappeared in European theater in pieces such as Friedrich Schiller's “Der Parasit.” In the seventeenth century, botanists were already describing parasitic plants such as mistletoe as parasites; in his 1735 standard work “Systema naturae,” Linnaeus first used the term “specie parasitica” for tapeworms in its modern biological sense.

Figure 1.1 Parasitos mask, a miniature of a theater mask of Greek comedy; terracotta, around 100 B.C. (From Myrine (Asia Minor); antiquities collection of the Berlin State Museums. Image: Courtesy of Thomas Schmid-Dankward.)

The delimitation of the term “parasite” to organisms which profit from a heterospecific host is very important for the definition itself. Interactions between individuals of the same species are thus excluded, even if the benefits of such interactions are very often unequally distributed in the colonies of social insects and naked mole rats, for instance, or in human societies. As a result, the interaction between parents and their offspring does not fall under this category, although the direct or indirect manner in which the offspring feed from their parent organism can at times be reminiscent of parasitism.

The principle of one side (the parasite) taking advantage of the other (the host) applies to viruses, all pathogenic microorganisms, and multicellular parasites alike. This is why we often find that no clear distinction is made between prokaryotic and eukaryotic parasites. With regard to parasites, we usually do not differentiate between viruses, bacteria, and fungi on the one hand and animal parasites on the other; we tend to see only the common parasitic lifestyle. Even molecules to which a function in the organism cannot be assigned are sometimes described as parasitic, such as prions, for example, the causative agent of spongiform encephalopathy, or apparently functionless “selfish” DNA plasmids that are present in the genome of many plants. Many biologists are of the opinion that only parasitic protozoa, parasitic worms (helminths), and parasitic arthropods are parasites in the strict sense of the term. Parasitology, as a field, is concerned only with those groups, while viruses, bacteria, fungi, and parasitic plants are dealt with by other disciplines. This restriction clearly hampers cooperation with other disciplines, something that seems antiquated in today's modern biology, where all of life's processes are traced back to DNA; it is gratifying that the boundaries have relaxed in recent years. However, eukaryotic parasites are distinguished from viruses and bacteria by their comparatively higher complexity, which implies slower reproduction and less genetic flexibility. These traits typically drive eukaryotic parasites to establish long-standing connections with their hosts, using strategies different from the “hit-and-run” strategies used by many viruses and bacteria....

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Chapter 1: General Aspects of Parasite Biology

- Chapter 2: Biology of Parasitic Protozoa

- Chapter 3: Parasitic Worms

- Chapter 4: Arthropods

- Answers to Test Questions

- Index

- End User License Agreement