- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Ancient Greek Civilization

About this book

The third edition of Ancient Greek Civilization is a concise, engaging introduction to the history and culture of ancient Greece from the Minoan civilization to the age of the Roman Empire.

- Explores the evolution and development of Greek art, literature, politics, and thought across history, as well as the ways in which these were affected by Greek interaction with other cultures

- Now includes additional illustrations and maps, updated notes and references throughout, and an expanded discussion of the Hellenistic period

- Weaves the latest scholarship and archeological excavations into the narrative at an appropriate level for undergraduates

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Ancient Greek Civilization by David Sansone in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Greek Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

THE GREEKS AND THE BRONZE AGE

- Cycladic Civilization

- Minoan Civilization

- The Greeks Speak Up

- The Emergence of Mycenaean Civilization

- The Character of Mycenaean Civilization

- The End of Mycenaean Civilization

The Bronze Age (ca. 3000 to 1200 BC) marks for us the beginning of Greek civilization. This chapter presents the arrival, in about 2000 BC, of Greek-speakers into the area now known as Greece and their encounter with the two non-Greek cultures that they found on their arrival, the civilizations known as Cycladic and Minoan. Cycladic civilization is notable for fine craftsmanship, especially its elegantly carved marble sculptures. The people of the Minoan civilization developed large-scale administrative centers based in grand palaces and they introduced writing to the Aegean region. These and other features of Minoan civilization greatly influenced the form taken by Greek civilization in its earliest phase, the Mycenaean Period (ca. 1650 to 1200 BC). Unlike Cycladic and Minoan civilizations, which were based on the islands in the Aegean Sea, Greek civilization of the Mycenaean Period flourished in mainland Greece, where heavily fortified palaces were built. These palaces have provided archaeologists with abundant evidence of a warlike society ruled by powerful local kings. Also surviving from the Mycenaean Period are the earliest occurrences of writing in the Greek language, in the form of clay tablets using the script known as “Linear B.” This script, along with Mycenaean civilization as a whole, came to an end around 1200 BC for reasons that are not at all clear to historians.

In the absence of written records, historians and archaeologists must use other features of a people’s culture to distinguish one group from another, features such as the style of their ceramic ware or the method by which they dispose of their dead. If, therefore, we place the beginning of Greek “history” at the point at which we begin to find written records left by Greek-speakers, we are in effect defining Greek history merely in terms of our own concerns over access to a particular form of evidence. As it happens, of all languages Greek is the one for which there exists the longest continuous record, extending from the fourteenth century BC until the latest edition of this morning’s Athenian newspaper. But the Greek people existed before that time and they spoke to one another using a form of the Greek language. It is our problem, not theirs, that they are more difficult to identify in the period before they began to write, the period that we refer to as their “prehistory.” That problem extends even to the questions of when the Greeks began to occupy the land around the Aegean Sea and where they lived before that. Many scholars are now convinced that the Greeks first migrated into the Aegean region at some time shortly before 2000 BC and that they came there from the area of the steppes to the north of the Black Sea. Interestingly, while the evidence for the date is largely of an archaeological nature, the evidence for the place is primarily linguistic.

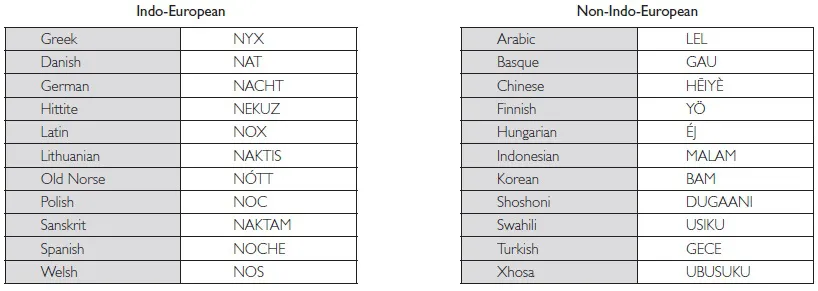

Greek is a member of the Indo-European family of languages, a family that comprises a number of languages spoken by peoples who have inhabited Europe and Asia. The Celtic, Germanic, Baltic, and Slavic languages are examples of European branches of the Indo-European family, while Sanskrit, Persian, and Hittite are Indo-European languages spoken in Asia. (When we speak of a “family” of languages we are using the word in the sense of a group of languages that are descended from a common ancestor, which in this case is a language that is no longer spoken but which can be hypothetically reconstructed on the basis of its descendants’ common features; see figure 4.) There is evidence of considerable movement of peoples who spoke Indo-European languages in the period around 2000 BC, and it is widely believed that it was in connection with this movement that Greek-speakers migrated into mainland Greece at roughly this time. Archaeological evidence exists that seems to be consistent with the appearance in Greece of a new group, or of new groups, of people in the centuries just before about 2000 BC, but the evidence is difficult to interpret and not all scholars are convinced that it necessarily points to a large-scale movement of people. The character of the artifacts that archaeologists have uncovered in mainland Greece from this period exhibits significant differences from the immediately preceding period, and several sites on the mainland have revealed evidence of destruction at this time. But the destruction is not universal, nor does it follow a neat pattern that might suggest the gradual progress of a new, belligerent population. If this is the period in which the Greeks first made their home in mainland Greece, it appears that we should think not so much in terms of a hostile invasion as a steady infiltration that resulted, here and there, in localized outbreaks of violence.

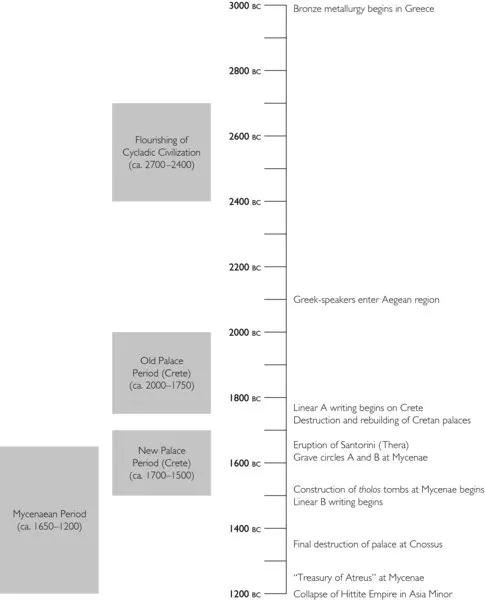

Timeline 2 The Bronze Age.

Figure 4 The word for “night” in some Indo-European and non-Indo-European languages.

Clearly, then, the Aegean region was not unoccupied when the people we know as the Greeks appeared on the scene. Whom did the Greeks encounter when they arrived and what happened to the earlier populations of Greece and the islands when the Greek-speakers entered the region? Unfortunately, because we are dealing with a period from which no written records survive, we are not in a position to know very much about who these people were or how long they had occupied the land that they were now forced to share with the Greek newcomers. For the evidence suggests that they did not simply disappear, their place being taken by a new group of inhabitants. As we will see, we do have written records for a slightly later period from the large island of Crete, records that show that the non-Greek language of Crete continuedin use until around 1500 BC. If the Greeks had driven out the earlier inhabitants or killed them off (for which, in any event, we have no evidence in the archaeological record), the language would have disappeared as well. In fact, communities of people who spoke a non-Greek language are said to have existed on Crete well into the first millennium BC. So it seems inevitable that Greek-speakers and non-Greek-speakers co-existed for an extended period of time. Eventually, the Greek language prevailed over the other language or languages, but recognition of that fact does not help us to know what happened to these non-Greek-speakers. Presumably, they and their descendants learned Greek and became themselves Greek-speakers. Also, presumably, they intermarried with the newly arrived Greek-speakers, so that the later population of Greece was a mixture, with any given individual increasingly likely, in the passage of time, to have among his or her ancestors members of both groups.

The pre-Greek population of the Aegean region included two groups of people who left behind evidence of notable cultural achievements. While we cannot be certain of the details regarding the extent and duration of the Greeks’ interactions with these people, there can be no doubt that those interactions left an enduring imprint on the later development of Greek culture. These people lived on the islands in and around the Aegean Sea, but their contacts with and influence upon the inhabitants of the Greek mainland are apparent. One group flourished on the cluster of about two dozen islands east of the Peloponnese known as the Cyclades (map 3). For this reason, and because we do not know what these people called themsel...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright

- FOREWORD LOOKING BACKWARD

- 1 THE GREEKS AND THE BRONZE AGE

- 2 IRON AGE GREECE

- 3 THE POEMS OF HESIOD AND HOMER

- 4 POETRY AND SCULPTURE OF THE ARCHAIC PERIOD

- 5 SYMPOSIA, SEALS, AND CERAMICS IN THE ARCHAIC PERIOD

- 6 THE BIRTH OF PHILOSOPHY AND THE PERSIAN WARS

- 7 SETTING THE STAGE FOR DEMOCRACY

- 8 HISTORY AND TRAGEDY IN THE FIFTH CENTURY

- 9 THE PELOPONNESIAN WAR: A TALE OF THUCYDIDES

- 10 STAGE AND LAW COURT IN LATE FIFTH-CENTURY ATHENS

- 11 THE TRANSFORMATION OF THE GREEK WORLD IN THE FOURTH CENTURY

- 12 GREEK CULTURE IN THE HELLENISTIC PERIOD

- AFTERWORD LOOKING FORWARD

- GLOSSARY

- INDEX

- EULA