- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Governance of Seas and Oceans

About this book

The governance of seas and oceans, defined as all forms of social participation in decision-making on the marine environment, is here mainly from a legal perspective view with the Law of the Sea as a determinant. The book presents the main aspects of maritime law and the history of its construction. The exploitation of living resources, minerals and marine energy reserves, maritime transport, marine ecosystems disturbance by a vessel traffic constantly increasing, are included.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Transformations in International Law of the Sea: Governance of the “Space” or “Resources”?

Chapter written by Florence GALLETTI.

1.1. Introductory remarks

In researching primary legal issues, and the legal instruments promoted by them enabling the governance of seas and oceans, the International Law of the Sea occupies an extremely important place. In both its ancient and current forms, it represents a foundation of rules and solutions utilized by States with coastal borders to impose maritime controls on marine waters. This Law of the Sea has almost wholly determined the current structure of administrative and legal divisions traced on the waters by governments and certain organizations. In this exercise, the concept of “marine spaces”, and especially of “marine spaces” to which Law of the Sea is applicable, has been essential. A very large portion of governments’ rights to act on the surface and beneath the seas depends on these spaces (section 1.2), and, most often, what is done with resources located in the seas (living or mineral resources) is also a result of them (section 1.3). The link between these two aspects must be explained, as they are increasingly intertwined. It is a transformation that involves considerable concerns regarding marine resources.

1.2. The importance of marine spaces in International Law of the sea

It is advantageous for us to define Law of the Sea, which determines the legal governance of seas and oceans, (section 1.2.1). This will help us to show the difference instilled between “marine” zones and “maritime” zones (section 1.2.2) and, whether it is public or private intervention on the seas and oceans that is intended, this slight difference is a fully operational one. The evolution of the Law of the Sea and the usages made of it by governments reveals the ongoing legal hold of coastal States over marine spaces; this is practised in various, rhizomatic forms – that is spread out and sometimes creeping, but in which the distance to the coast (via the legal concept of the “baseline”) remains an essential point, and the horizontal division of marine waters both under the jurisdiction of States or beyond it, a strong constant (section 1.2.3).

1.2.1. Definitions of International Law of the sea: a keystone of the governance of maritime spaces

The question of governance of maritime spaces cannot be set without a definition exercise. In a restricted sense, it is a set of institutions, legal rules and processes enabling the adoption of an institutional and legal framework for action, and then the development of related public or private interventions, on the delinated space. Despite its importance, the International Law of the Sea is often poorly defined, or defined by default by differentiating it from other, more sector-specific legal disciplines pertaining to activity at sea. It is related in particular to maritime law, a very ancient concept used in the past to address issues arising both from private laws having to do with maritime activity and international public law for marine activities [PON 97]. This has resulted in widespread (and quite understandable) confusion. Today, however, maritime law pertains mostly to the specific commercial activity of maritime shipping, and is defined as “all legal rules pertaining to navigation on the seas” [ROD 97] or as “all legal rules pertaining to private interests engaged at sea”1 [SAL 01]. More rarely, some specialists attribute a broader definition to maritime law, seeing it, for example, as “all rules pertaining to the various relationships having to do with the utilization of the sea and the exploitation of its resources2 [LǾP 82a], or study it in parallel with International Law of the sea3. However, the two subjects are separate. The International Law of the Sea addresses seafaring activities in a more complete manner; these naturally include navigation, but from another angle, which can bring the two types of law together and render them complementary. The International Law of the Sea, widely referred to as such since the first Geneva Conference on the Law of the Sea in 1958, is more relevant to matters of governance of spaces at sea. With it, oceans and seas are not without legal rules and arguments; on the contrary, a field of law is specifically dedicated to them [DAU 03].

One of its definitions presents it as “all rules of International Law pertaining to the determination and subsequent status of maritime spaces, and pertaining to the system of activities framed by the marine environment”4 [SAL 01]. A more geopolitically oriented definition presents it as “Law regulating relations between States concerning the utilization of the sea and the exercise of their power over maritime spaces”5 [LǾP 82b]. Both of these definitions emphasize a spatial element that is highly determinative of the holding of rights by governments and of the exercise of these rights in relation to other governments.

The context of the Law of the Sea involves the pre-eminent position of the “State” in several senses. The central government is a favored subject in International Law, alongside the various international organizations in which this quality is recognized6 [DAI 02]. Because it is situated under the aegis of general International Law, the Law of the Sea obeys the same operating principles, those of an “international legal order” in which States remain vital actors but are very free for the creation of multilateral or bilateral legal rules. It results from this that the State is the vector of the rules making up a system of governance applied to its continental, applied to its continental or island territory, and to the marine spaces that are extensions of these (adjacent maritime spaces). It is vector directly influenced by International Law or by its own inventiveness and (most often) within the limits of action permissible by written (conventional) or customary International Law. Outside of these marine the vector spaces under State control, concepts such as “right to fly flag and flag law” or recourse to “nationality” are all forms of extension – on the high seas – of the national Law of a State (or an institution such as the European Union (EU)) over often far-flung waters which are no longer linked by geographic proximity and legal bonds “of sovereignty” or “of jurisdiction” between the State and these marine spaces.

1.2.2. Marine spaces considered by law: the interest of qualifying maritime zones

All marine spaces, as far as they are able to be distributed, identified and described by life sciences or biogeography, for example, are not all spaces considered by law. The existence of seas and oceans is a fact that can be understood scientifically, but the existence of a Law of the Sea associated with these bodies of water does not necessarily follow from this. For this to occur, a shift is required between the term “marine zones” and the concept of “maritime zones”. In geographical terms, a “marine” or “maritime” zone – the terms are used almost interchangeably – may designate any part of the sea of some geographic sector in which a given activity takes place; this means that we see for example that gulfs, coastal areas, and shorelines are designated but without any legal consequence [LUC 03]7. When the desire or obligation for public intervention and regulation of an area of marine zones arises, legal definition exercises take place.

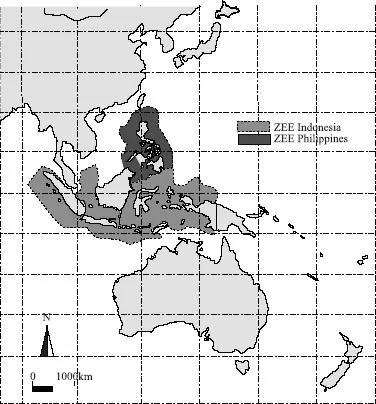

In legal terms, the concept of a “maritime zone” designates a marine zone or marine space to which a legal system is applicable. The legal term “maritime zone” is applicable only to marine spaces, each corresponding to its own legal system8 [LUC 03]. Thus, via various successive conventions and conferences on the Law of the Sea, a large number of maritime zones have been established by coastal States according to the legal marine spaces predefined in the conventions, of which the most recent and consequential was the United States Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS)9 of December 10, 1982, sometimes also known as the Montego Bay Convention (MBC). In addition to common maritime zones which have now become relatively classic, such as internal waters10, territorial seas11, contiguous zones12, exclusive economic zone (EEZ)13, continental shelves14, high seas15 and the international zone of seabed called “the Area”, there are now maritime zones arising from the first zones and thus from least ambitious rights of establishment according to the legal adage “he who can do more can do less”, such as fishing zones, ecological protection zones (EPZs), and possibly integrated management coastal zones (IMCZs) [GHE 13], etc. To all this, we must also add specific configurations of marine spaces which the Law of the Sea has sanctioned and to which it has granted, subject to compliance with certain conditions, a legal status that gives rise to specific legal effects: islands16, bays17, straits18, international canals, low-tide elevations19, archipelagic waters20, etc. (such as in the Philippines or Indonesia; see Figure 1.1). The definition of these marine spaces is not only a simple typology conveniently available for coastal States wishing to have them recognized or established for their own benefit; but, it is always accompanied by a legal system of rights and obligations regarding maritime zone x for the State concerned (coastal State, port State, flag-holding State, with adjacents coasts, etc.) [PAN 97]. These situations can be more complex; a double legal system can exist in one maritime space, with the typical case being that of territorial waters (or two adjoining territorial seas) containing a strait used for international navigation, such as the Strait of Bonifacio between France and Italy. If the analysis of spaces greatly affects the delimitation of fishing activity or navigation (two activities that are particularly highly developed and sanctioned in the Law of the Sea [LUC 90, LUC 96b]), the question of marine resources, their protection and their development also plays a role.

Figure 1.1. Archipelagic waters and exterior limits of the two EEZs of two archipelagic States in the sense of Int...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Table of Contents

- Title

- Copyright

- Foreword

- 1: Transformations in International Law of the Sea: Governance of the “Space” or “Resources”?

- 2: The Governance of the International Shipping Traffic by Maritime Law

- 3: Marine Pollution: Introduction to International Law on Pollution Caused by Ships

- 4: Management and Sustainable Exploitation of Marine Living Resources

- 5: Marine Renewable Energies: Main Legal Issues

- 6: Socio-economic Evaluation of Marine Protected Areas

- 7: Integrated Management of Seas and Coastal Areas in the Age of Globalization

- 8: Ocean Industry Leadership and Collaboration in Sustainable Development of the Seas

- List of Authors

- Index

- End User License Agreement

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Governance of Seas and Oceans by André Monaco,Patrick Prouzet in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Ciencias físicas & Oceanografía. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.