eBook - ePub

"Farewell, My Nation"

American Indians and the United States in the Nineteenth Century

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The fully updated third edition of "Farewell, My Nation" considers the complex and often tragic relationships between American Indians, white Americans, and the U.S. government during the nineteenth century, as the government tried to find ways to deal with social and political questions about how to treat America's indigenous population.

- Updated to include new scholarship that has appeared since the publication of the second edition as well as additional primary source material

- Examines the cultural and material impact of Western expansion on the indigenous peoples of the United States, guiding the reader through the significant changes in Indian-U.S. policy over the course of the nineteenth century

- Outlines the efficacy and outcomes of the three principal policies toward American Indians undertaken in varying degrees by the U.S. government – Separation, Concentration, and Americanization – and interrogates their repercussions

- Provides detailed descriptions, chronology and analysis of the Plains Wars supported by supplementary maps and illustrations

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

The “Indian Question”

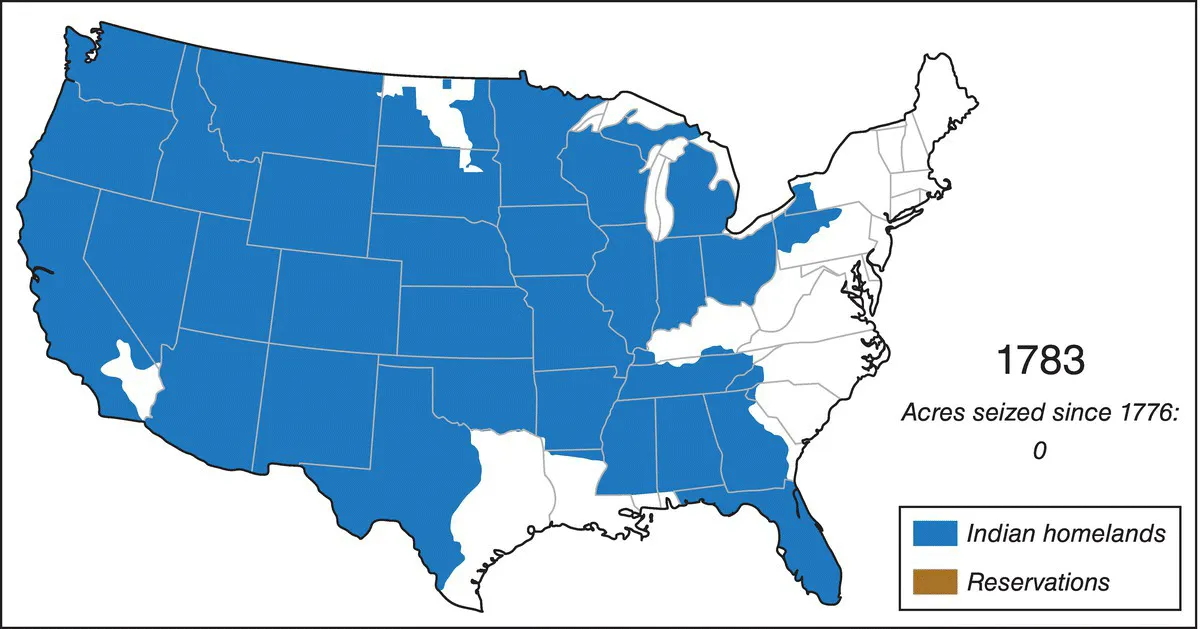

Map 1.1 1783.

(Reproduced by permission of Dr. Claudio Saunt, http://www.ehistory.org/, University of Georgia.)

In Need of a Solution

They could now get on with the task of burying the dead. For the previous three days, the last three of the old year, a ferocious winter storm had pummeled the upper plains. By the morning of New Year’s Day, 1891, the blizzard had blown itself out, and the sun began to break through the gray clouds. As the sky cleared, a train of wagons accompanied by individuals on horseback, both Sioux and Americans, set out from Pine Ridge agency, situated near the southwestern corner of the Sioux’s Pine Ridge reservation in South Dakota. The party’s destination was Wounded Knee Creek some twenty miles to the east. There, Sioux and troops of the U.S. Seventh Cavalry had clashed on December 29, 1890, leaving hundreds of Sioux either killed or severely wounded.

The Sioux, absorbed in distressing thoughts, crossed the bleak prairie through the frigid morning air, along the trail leading to where so much ended. Many precious lives were lost. The beautiful dream had died too. Why? Was there no means left to save the old treasured ways? Was all hope finally exhausted for the Indian people? They remembered the spiritual path that many recently had followed with such passion. It was a seductive dream, teeming with confident anticipation of deliverance for Indian peoples and escape from the white oppressors. At the end of that intoxicating path lay not rebirth but, instead, this agonizing moment, this appalling conclusion of death and finality.

The Sioux who fell at Wounded Knee were followers of the Paiute mystic Wovoka, whose message combining Indian mysticism and Christian millennialism had found a substantial following in the late 1880s among the war weary, beaten-down western tribes. A dozen years had passed since the victory of the United States in the Great Plains wars that completed the Indians’ subjugation. The mystic’s message of God’s forthcoming deliverance of the Indian people raised hopes and spawned jubilation among tribes from the Pacific Northwest to Oklahoma.

Wovoka described in great detail his vision and the instructions from the Divine to all who would listen. God promised in the fullness of time to expel the white people and return the earth to the Indians, the living as well as the dead—and give them back the buffalo.1 Indians must learn a special dance and perform it regularly, Wovoka was instructed. The more often the Ghost Dance was performed, the sooner God would vanquish the white people and return the earth to the Indians.

News spread rapidly about Wovoka’s vision and the possible return of old-fashioned life. Deeply discouraged by the long struggle with the United States, its army and bureaucrats, many Indian people turned joyously, some even desperately, to this forthcoming restorative event. They eagerly accepted Wovoka’s revelations as divine inspiration and, for that reason, faithfully performed the dance. Devotees prepared themselves for their rebirth and for the vanquishing of the white man who had brought such chaos and unhappiness to their lives.

Federal authorities, alarmed by the mounting frenzy, in the autumn of 1890 ordered the Ghost Dance halted. Intimidated believers acquiesced across the West, including most of the Sioux, the largest tribe on the Great Plains. Nonetheless, a significant number of Sioux refused and fled to the Dakota Badlands to continue the dance faithfully. Leaving their encampment on the Sioux’s Cheyenne River reservation and making their way peacefully and cautiously southward toward the Pine Ridge reservation, Chief Big Foot and his band nevertheless were intercepted by troops of the Seventh Cavalry and taken as prisoners to the small settlement of Wounded Knee. On the morning following their capture in late December 1890, soldiers moved to disarm the Indians. Their resistance quickly turned into a melee between Sioux and soldiers, with shots exchanged. The Seventh Cavalry responded with a volley of rifle, pistol, and artillery fire that left hundreds of Sioux men, women, and children either killed or severely wounded. The massacre at Wounded Knee destroyed people’s confidence in Wovoka’s promises and their faith in the Ghost Dance.

Wounded Knee was the last battle, as the federal government termed the event, between the Indians and the United States Army, although no one knew it at the time. War Department annual reports throughout the 1890s indicated that the military anticipated other outbreaks of trouble. Faith in Wovoka’s message and the Ghost Dance faded quickly after Wounded Knee; with all hope gone, no tribe dared to rise in resistance against the United States.

The full significance of Wounded Knee emerged in time: it was the conclusion of a four-century-long struggle with America’s First Nations. That struggle had embroiled the United States for longer than a century and, before that, the European imperial powers for almost three centuries. It epitomized the greatest reality of the American Indian experience during that four-century-long struggle: the unalterable reality of white dominance over the continent and the lives and destinies of its indigenous peoples. It also demonstrated the utter failure of federal Indian policy to fashion a workable and mutually acceptable solution to what whites called the “Indian Question.”

Wounded Knee also became an historical allegory that is, at the same time, artificial and accurate. For many, that event symbolizes the tragic passing of “Indian America,” although most tribes had experienced their own “Wounded Knee,” their own culminating episode, years, decades, or centuries before. Many view Wounded Knee as a microcosm of Indian history since the coming of the white man, characterized by victimization and cultural imperialism, futile resistance and absolute defeat.

This theme gained a wide popular audience with Dee Brown’s best seller whose title, Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, drew from Stephen Vincent Benét’s poem “American Names.” “I shall not be there. I shall rise and pass. Bury my heart at Wounded Knee,” Benét reminded America of its once proud and free native peoples. That tragic event endures as a reminder of the dreadful human cost paid for the “Winning of the West,” for realizing the republic’s “Manifest Destiny,” for conquering the lands comprising the contiguous United States of America.

Between 1776 and 1887, white conquerors would claim as their own 1.5 billion acres of land possessed by native peoples. The expansion of the American population westward during the first century of the national experience was spectacular in its swiftness and scope. Surging outward from the Atlantic seaboard and across the Appalachian chain, Americans moved with intense and unyielding determination to acquire and settle a vast western domain: first east, then west of the Mississippi. By 1850, the nation stretched from the Atlantic to the Pacific—“from sea to shining sea,” as Americans heralded jubilantly in song. Many still dreamed of adding Canada, more of Mexico, and various Caribbean islands, such as Cuba, to the expansive republic.

Each year Americans filled in the frontier until finally, in the late nineteenth century, the superintendent of the census for the United States declared that the American frontier had ceased to exist. A Census Bureau bulletin in 1890 concluded: “Up to and including 1880 the country had a frontier of settlement, but at present the unsettled area has been so broken into by isolated bodies of settlement that there can hardly be said to be a frontier line.” In a twist of irony, the announcement came in the same year as the massacre at Wounded Knee.

The vast locales acquired and settled by Americans were home to various native groups. First reports of the white invaders may have caused indifference or simple curiosity among Indians, but soon they judged these strangers a threat. The newcomers moved with a firm resolve to displace them, regulate them, and occupy their patrimony. The staggering migration of people, acquisition of territory, and settlement of the frontier was the foremost source of a near constant state of friction and hostility between the United States government, its citizens, and the Indians. In the face of this aggressive drive westward, the pattern most representative of United States–Indian relations was set early. Over the many years, it was subject to the ebb and flow of events and to differing views of policy, but through it ran a strain of unremitting determination to dislodge the indigenous inhabitants of the western lands. Government might from time to time relent; Americans wanting land never did. In 1879, a Wyoming newspaper foretold an inevitable outcome. “The same inscrutable Arbiter that decreed the downfall of Rome has pronounced the doom of extinction upon the red men of America. To attempt to defer this result by mawkish sentimentalism … is unworthy of the age.”

One central, overriding concern confronted the managers of the nation’s westward expansion from the birth of the republic in 1787 onward: what should be done with the American Indians? Most whites considered them a dangerous impediment to the republic’s territorial, cultural, and economic aspirations. The interracial tensions caused by expansion and the persistent demands from citizens for protection against Indian attacks meant that the United States had to solve the “Indian Question.”

Many answers to this question were advanced, both in and out of government. Some proposed creating a geographic boundary that would separate Indian lands from that of American land, much as the British had done in their proclamation of 1763. Great Britain had designated a frontier line along the Appalachian Mountains, with Indian lands to the west and American territory to the east of the boundary line. If the United States government adopted a comparable solution, advocates argued, Indians might maintain their accustomed way of life on land of their own in the trans-Appalachian West, free from white encroachment.

Others suggested that culturally transforming the American Indians into “Indian Americans,” then assimilating them into the dominant society was the wisest course. Indians were well aware of the existence, indeed the predominance, of this kind of thinking on the part of Americans; although, as Brian W. Dippie states in The Vanishing American, “This gift of civilization—the ultimate gift, to the whites’ way of thinking … always seemed to please the donor more than the recipient.”

Still others, such as Montana Territorial governor James M. Ashley, urged extermination. “The Indian race on this continent has never been anything but an unmitigated curse to civilization, while the intercourse between the Indian and the white man has been only evil,” Ashley asserted in 1870. It will remain so, he stressed, “until the last savage is translated to that celestial hunting ground for which they all believe themselves so well fitted, and to which every settler on our frontier wishes them individually and collectively a safe and speedy transit.”

Abundant suggestions, prudent and foolish, mean-spirited and generous, were offered because most Americans thought that a solution to the Indian Question was needed. Indian Commissioner John Quincy Smith, in 1876 at the conclusion of the Plains Wars, observed, “For a hundred years the United States has been wrestling with the ‘Indian question.’” And, try as it may, the lasting resolution so urgently sought remained sorely elusive. General William T. Sherman, in a comment to General John M. Schofield, reflected the exasperation this produced in generations of Americans, “The whole Indian question is in such a snarl, that I am utterly powerless to help you by order or advice.”

This problem of what means would solve the Indian Question shaped and reshaped the relationship of the republic with America’s native peoples. The United States was a half-century old in the 1830s when federal bureaucrats settled upon the initial solution; however, the Indian Question had roots stretching back to colonial times.

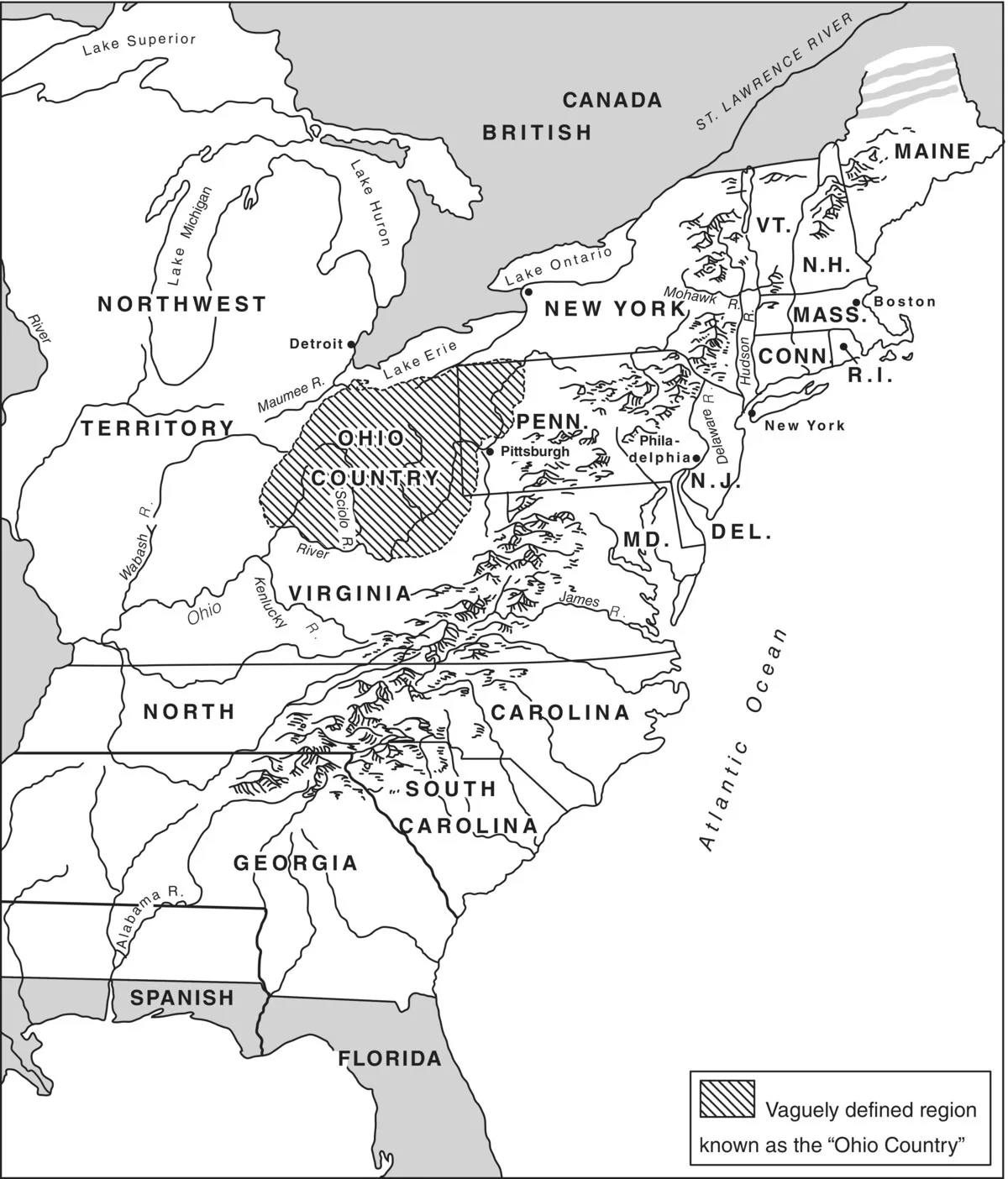

Breaching the Ohio Country Barrier

Americans had initiated an experiment with their Revolution the likes of which the world had never seen before: establishing a nation on the principle that liberty was a human right, an unalienable right from God—not the monarch, nor the president, nor legislators. Liberty was not license to act as irresponsibly as one chose. Liberty was acting in any manner a person wished as long as it did not interfere with the exercise of the rights of others. Above all, liberty to Americans meant freedom from a big, powerful, intrusive national government (like the British government) that would be kept out of the people’s lives and possessions. For so many Americans, heading west meant heading to lands where life could be lived at its freest, with minimum restrictions. However, the impending movement of liberty-minded Americans into the nation’s first West would spawn, with terrible irony, life-altering intrusion into the lives and liberty of native populations.

White settlers, as soon as the American Revolution ended, planned to press forward into the western lands for which they had fought so hard against the British and the Indians. A great many were veterans of the Revolution, compensated by their debt-ridden state and national governments for their time in the military with land grants in the Ohio Country. It was an appealing prospect. Available lands were no longer plentiful in New England, where families averaged seven living children. The South with its slave economy was not attractive either, particularly to those with little or no capital for start-up money. The best bet, especially for the young, lay across the Pennsylvania corridor and into the Ohio Country in search of homes, where acreage was abundant and inexpensive. However, a very serious problem existed for them: although Great Britain granted these lands to the United States when the Revolutionary War ended, the native peoples who had thought for centuries that the land beyond the Appalachian Mountains was their own to keep forever were determined to resist.

Map 1.2

The United States government hoped both to promote westward expansion and minimize hostilities with tribes by the wise management of Indian affairs. It fell principally to the United States Congress to fashion the agenda for achieving these objectives. The Articles of Confederation initially, and then the Constitution for the United States, granted Congress regulatory power over commerce and treaty making. Those powers allowed the legislative branch to exercise sweeping control over Indian affairs, which Congress attempted to manage using two tools: the passage of legislation and the negotiating of formal treaties with the various tribes.

Employing its legislative power, Congress created new laws to regulate white settlement on Indian lands and manage the purchase and sale of tribal lands by...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1 The “Indian Question”

- 2 The Initial Solution

- 3 The Travails of Mid Century

- 4 The Plains Wars, Phase I: Realizing Concentration

- 5 The Plains Wars, Phase II: Enforcing Concentration

- 6 The Search for a New Order

- Bibliographical Essay

- Index

- End User License Agreement

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access "Farewell, My Nation" by Philip Weeks in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.