eBook - ePub

From Microstructure Investigations to Multiscale Modeling

Bridging the Gap

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

From Microstructure Investigations to Multiscale Modeling

Bridging the Gap

About this book

Mechanical behaviors of materials are highly influenced by their architectures and/or microstructures. Hence, progress in material science involves understanding and modeling the link between the microstructure and the material behavior at different scales. This book gathers contributions from eminent researchers in the field of computational and experimental material modeling. It presents advanced experimental techniques to acquire the microstructure features together with dedicated numerical and analytical tools to take into account the randomness of the micro-structure.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access From Microstructure Investigations to Multiscale Modeling by Delphine Brancherie, Pierre Feissel, Salima Bouvier, Adnan Ibrahimbegovic, Salima Bouvier,Delphine Brancherie,Pierre Feissel,Adnan Ibrahimbegovic, Salima Bouvier, Delphine Brancherie, Pierre Feissel, Adnan Ibrahimbegovic in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Mechanics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Synchrotron Imaging and Diffraction for In Situ 3D Characterization of Polycrystalline Materials

1.1. Introduction

The last few years have seen material science progressing rapidly into three-dimensional (3D) characterization at different scales (e.g. atom probe tomography [PHI 09], transmission electron microscopy tomography [WEY 04], automated serial sectioning tomography [UCH 12, ECH 12] and X-ray tomography [MAI 14]). A wealth of 3D data sets can now be obtained with different modalities, allowing the 3D characterization of phases, crystallography, chemistry, defects or damage and in some cases strain fields.

In the last 10 years, one particular focus of the 3D imaging community (like 2D in its time with the advent of EBSD characterization) has been on obtaining reliable three-dimensional grain maps. As most structural materials are polycrystalline and the mechanical properties are determined by their internal microstructure, this is a critical issue. There has been considerable effort to develop characterization techniques at the mesoscale, which can image typically 1 mm3 of material with a spatial resolution in the order of micrometers.

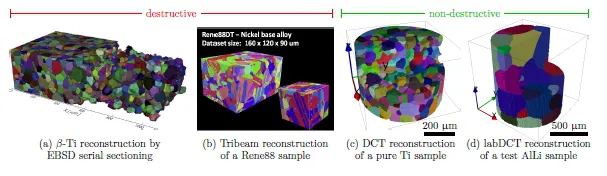

Among 3D characterization, an important distinction exists between destructive and non-destructive techniques. Serial sectioning relies on repeated 2D imaging (which may include several modalities) of individual slices, where a thin layer of material is removed between each observation (see Figure 1.1(a,b)). The material removal can be achieved via mechanical polishing [ROW 10], ion [DUN 99, JIR 12] or femtosecond laser ablation [ECH 15] in a dedicated scanning electron microscope (SEM). Considerable progress has been made in this line in the last decade, bringing not only high-quality measurements in 3D of grain sizes and orientations but also detailed grain shapes and grain boundary characters. The most serious threat of serial sectioning is, however, the destruction of the sample.

In parallel, the advent of third-generation synchrotrons worldwide, with ESRF at the forefront, brought hard X-rays, with their high penetrating power, to the structural material science community. X-ray computed tomography (CT) rapidly developed as a key observation tool, allowing the non-destructive bulk evaluations of all types of materials [MAI 14]. This made the in situ study of damage possible using specifically designed stress rigs [BUF 10]. Unfortunately, CT imaging relies on absorption and phase contrasts and remains blind to crystal orientation. Accessing crystallographic information in the bulk of polycrystalline specimens (average orientation per grain) was subsequently achieved using the high penetrating power of hard X-rays and leveraging diffraction contrast. The pioneering work of Poulsen took advantage of high-brilliance synchrotron sources to study millimeter-sized specimens by tracking the diffraction of each individual crystal within the material volume while rotating the specimen over 360°. This led to the development of 3DXRD [POU 04] and its several grain mapping variants (DCT [LUD 08], HEDM [LIE 11], DAGT [TOD 13]). Among them, the near-field variant called diffraction contrast tomography (DCT, see Figure 1.1(c)) will be detailed in section 1.2.7.

Figure 1.1. Various examples of grain mapping techniques (spatial resolution indicated in brackets): (a) serial sectioning through mechanical polishing (0.45 μm in the XY plane, 1.48 μm in the Z direction) [ROW 10], (b) tribeam (laser ablation, 0.75 μm) [ECH 15], (c) DCT near-field imaging (1.4 μm) [PRO 16a], (d) labDCT reconstruction with grain shape and orientations (5 μm, courtesy of Xnovotech). For a color version of the figure, see www.iste.co.uk/brancherie/microstructure.zip

This chapter is organized as follows: the fundamentals of 3D X-ray characterization of structural materials are reviewed in section 1.2 from pure absorption contrast to diffraction contrast tomography. Then, a recently developed stress rig adapted for DCT is presented in section 1.3. Finally, section 1.4 details how to use experimental 3D grain maps in finite-element crystal plasticity calculations.

1.2. 3D X-ray characterization of structural materials

1.2.1. Early days of X-ray computed tomography

As most materials are opaque to optic light, people have long relied on the observation of object surfaces and/or destructive cut to assess various evolutions of physical phenomenon or diagnostics. With the advent of X-rays in the 20th Century, both easy to produce and capable of penetrating significantly through matter, a large number of works have been devoted to develop a technique that would allow to see the invisible.

The theoretical bases of tomography were laid down by J. Radon in 1917 (see section 1.2.4), and the first part of the 20th Century saw the development of what we call today conventional tomography. This allowed to record sectional image through a body by moving X-ray source and the film in opposite directions during the exposure. However, the images remained difficult to interpret.

The development of computer power in the second part of the 20th Century let G. Hounsfield build the first computed tomography (CT) scanner in 1971. At that time, the spatial resolution achieved was about 3 mm and the resolution of the images produced after reconstruction by a Data General Nova 16 bits minicomputer was 80 × 80 pixels. The scanner was installed in an English hospital, where the first brain scan was performed on a patient.

In the United States, A. Cormack independently developed a similar system, and both of them received the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1979 for their invention. Since then, CT scanning has been used in medical practice as a powerful tool to help diagnostic.

1.2.2. X-ray absorption and Beer...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Table of Contents

- Title

- Copyright

- Preface

- 1 Synchrotron Imaging and Diffraction for In Situ 3D Characterization of Polycrystalline Materials

- 2 Determining the Probability of Occurrence of Rarely Occurring Microstructural Configurations for Titanium Dwell Fatigue

- 3 Wave Propagation Analysis in 2D Nonlinear Periodic Structures Prone to Mechanical Instabilities

- 4 Multiscale Model of Concrete Failure

- 5 Discrete Numerical Simulations of the Strength and Microstructure Evolution During Compaction of Layered Granular Solids

- 6 Microstructural Views of Stresses in Three-Phase Granular Materials

- 7 Effect of the Third Invariant of the Stress Deviator on the Response of Porous Solids with Pressure-Insensitive Matrix

- 8 High Performance Data-Driven Multiscale Inverse Constitutive Characterization of Composites

- 9 New Trends in Computational Mechanics: Model Order Reduction, Manifold Learning and Data-Driven

- List of Authors

- Index

- End User License Agreement