![]()

Chapter 1

Assessing the Community Maturity from a Knowledge Management Perspective

Knowledge is considered as a strategic resource in the current economic age. Strategies, practices and tools for enhancing knowledge sharing and knowledge management (KM) in general have become a key issue for organizations. Despite the demonstrated role of communities in sharing, capturing and creating knowledge, the literature is still missing standards for assessing their maturity. Even if several knowledge-oriented maturity models are provided at the enterprise level, few are focusing on communities as a mechanism for organizations to manage knowledge. This chapter proposes a new Community Maturity Model (CoMM) that was developed during a series of focus group meetings with professional KM experts. This CoMM assesses members’ participation and collaboration, and the KM capacity of any community. The practitioners were involved in all stages of the maturity model’s development in order to maximize the resulting model’s relevance and applicability. The model was piloted and subsequently applied within a chief knowledge officers’ (CKO) professional association, as a community. This chapter discusses the development and application of the initial version of CoMM and the associated method to apply it.

1.1. Introduction

Knowledge is considered as a key competitive advantage [PEN 59], therefore several knowledge-intensive organizations are investing in methods, techniques and technologies, to enhance their KM, among others through communities. The community-based KM approach has become one of the most effective instruments to manage organizational knowledge [BRO 91]. Indeed, Wenger [WEN 98] argues that knowledge could be shared, organized and created within and among the communities. He posits that communities of practice (CoPs) are the company’s most versatile and dynamic knowledge resource. They form the basis of an organization’s ability to know and learn. From practical and theoretical perspectives, we can find several types of communities (of practice (CoPs), virtual CoP (VCoP), of interest (CoIN), of project, etc.). Furthermore, since they mostly deal with knowledge, Correa et al. [COR 01] call them knowledge communities (KCs) and consider them as a key KM resource through socialization [NON 95, EAR 01].

Nowadays, due to the increasing use of communities in the professional context and the exponential growth of social networks and online communities [RHE 93], it is more important than ever for modern organizations to assess the quality of their outcomes, and to understand their role in intra- and interorganizational KM settings. To establish such an understanding, many questions need to be answered, including but not limited to: how do we determine the type of a community? Under which conditions are communities more productive and useful for organizations? How they can be beneficial to KM: knowledge sharing, capturing and co-creation? Which attitudes and capabilities should individuals develop to better involve themselves within communities? What kind of facilitation means do they need for operating better? Are there different levels of quality that can be recognized and that communities should aim for? Which role should knowledge and collaboration technologies play to foster productivity? How can we measure the impacts of communities on organizational performance? Therefore, it is clear today that organizations urgently need guidance on those issues and on how to take advantage from the KCs’ production and to efficiently use and manage them for better sharing, learning and innovating.

Several scholars have proposed models and approaches to assess communities [VER 06, MCD 02]. One way to assess the overall characteristics, management, evolution and performance of a community isthrough a maturity model approach with a KM-oriented perspective. Maturity models have been used extensively in quality assurance for product development [FRA 02].

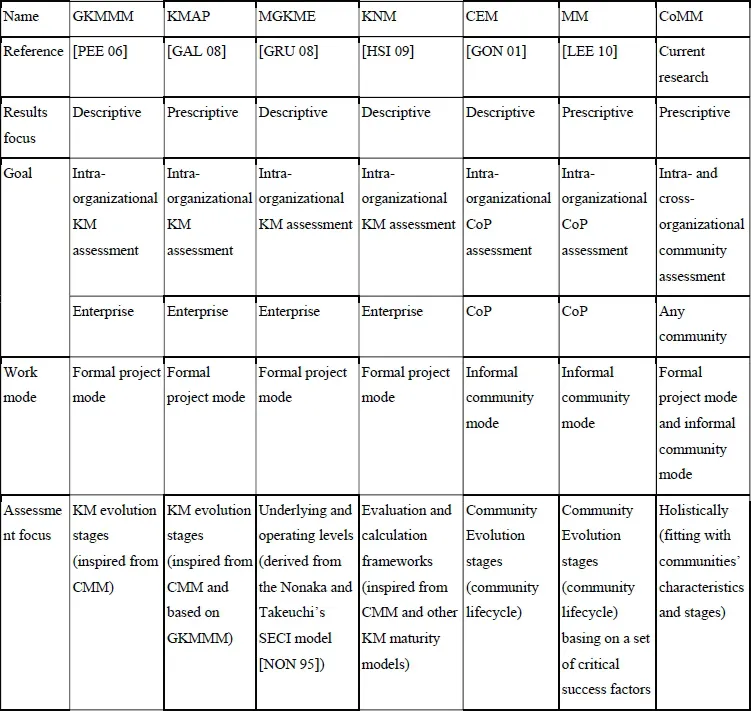

Few efforts have been reported on using maturity models to assess communities, especially from a KM perspective. Most of the KM models proposed in the literature (such as Global Knowledge Management Maturity Model (GKMMM [PEE 06]), Knowledge Management Assessment Project (KMAP [GAL 08]), Model for General Knowledge Management within the Enterprise (MGKME [GRU 08]) and Knowledge Navigator Model (KNM [HIS 09])) are either very generic at the enterprise organizational level and/or not enough specific to assess communities. Very few community-oriented KM maturity models have been proposed [GON 01, LEE 10]. Even if these examples of models present an interesting theoretical perspective, little is reported on their application and evaluation. They are not specifically KM oriented and most of them focus only on CoPs. This chapter is an attempt to address this gap and to propose a new model for assessing communities from a KM perspective sufficiently generic to be applied to any community or social network. It addresses the following research question:

How do we determine the maturity level of a community from a KM perspective?

This question can be divided in two subquestions:

– What characteristics describe a community’s maturity?

– What steps need to be taken to measure a community’s maturity in terms of KM?

This chapter advances a CoMM that was developed in cooperation with a focus group consisting of professional KM experts. The CoMM is intended to be usable by practitioners for conducting self-assessments. This chapter first discusses the development of the initial version of the CoMM and the associated method to apply it, and second an application and evaluation that provide evidence of proof of value and proof of use in the field. The purpose of this chapter is to further serve as a starting point for future research in this area.

The remainder of this chapter is structured as follows. We first present the theoretical background related to maturity models. Next, we introduce our research approach to develop the CoMM, based on the design science perspective. Then, we report on the field application of the CoMM within a CKO professional association. Lastly, we present the implications for research and practice, followed by our conclusion that summarizes the limitations of this ongoing research and presents future research directions.

1.2. Background

The word maturity is equivalent to “ripeness”, which means having reached the most advanced stage in a process. Maturity is a quality or state of becoming mature [AND 03]. Paulk et al. [PAU 93, p. 21] define process maturity as “the extent to which a specific process is explicitly defined, managed, measured, controlled, and effective”. They describe the transition from an initial to a more advanced state, possibly through a number of intermediate states [FRA 02]. Maturity models position all the features of an activity on a scale of performance under the fundamental assumption of ensuring plausible correlation between performance scale and maturity levels. A higher level of maturity will lead to a higher performance [FRA 03]. “At the lowest level, the performance of an activity may be rather ad hoc or depend on the initiative of an individual, so that the outcome is unlikely to be predictable or reproducible. As the level increases, activities are performed more systematically and are well defined and managed. At the highest level, ‘best practices’ are adopted where appropriate and are subject to a continuous improvement process” [FRA 03, p. 1500].

1.2.1. Maturity models

Approaches to determine process or capability maturity are increasingly applied to various aspects of product development, both as an assessment instrument and as part of an improvement framework [DOO 01]. Most maturity models define an organization’s typical behavior for several key processes or activities at various levels of “maturity” [FRA 03]. Maturity models provide an instantaneous snapshot of a situation and a framework for defining and prioritizing improvement measures. The following are the key strengths of maturity models:

– They are simple to use and often require simple quantitative analysis.

– They can be applied from both functional and cross-functional perspectives.They provide opportunities for consensus and team building around a common language and a shared understanding and perception.

– They can be performed by external auditors or through self-assessment.

One of the earliest maturity models is Crosby’s Quality Management Maturity Grid (QMMG) [CRO 79], which was developed to evaluate the status and evolution of a firm’s approach to quality management. Subsequently, other maturity models have been proposed for a range of activities including quality assurance [CRO 79], software development [PAU 93], supplier relationships [MAC 94], innovation [CHI 96], product design [FRA 02], R&D effectiveness [MCG 96], product reliability [SAN 00] and KM [HSI 09]. One of the best-known maturity models is the Capability Maturity Model (CMM) for software engineering (based on the Process Maturity Framework of Watts Humphrey [PAU 93], and developed at the Software Engineering Institute (SEI)). Unlike the other maturity models, CMM is a more extensive framework in which each maturity level contains a number of key process areas (KPAs) containing common features and key practices to achieve stated goals. A number of studies of the software CMM have shown links between maturity and software quality (e.g. [HAR 00]). This model (with multiple variations) is widely used in the software industry.

Nowadays, several maturity models have been proposed that aim at clearly identifying the organizational competences associated with the best practices [FRA 02]. In practice, however, many maturity models are intended to be used as part of an improvement process, and not primarily as absolute measures of performance [FRA 02]. Few maturity models have been validated in the way of performance assessment. An exception is Dooley et al.’s study [DOO 91] that demonstrated a positive correlation between new product development (NPD) process maturity and outcome.

1.2.2. Knowledge-oriented maturity models

The interest in KM dates back to the early 1990s when companies realized the strategic value of knowledge as a competitive resource and a factor of stability for their survival [SPE 96]. There is more than one definition of KM. Mentzas [MEN 04, p. 116] defines KM as the “discipline of enabling individuals, teams and entire organizations to collectively and systematically create, share and apply knowledge, to better achieve the business objectives”. KM generally refers to how organizations create, retain and share knowledge [ARG 99, HUB 91]. It involves the panoply of procedures and techniques used to get the most from an organization’s tacit and codified know and know-how [TEE 00]. According to McDermott [MCD 02], “tacit knowledge is the real gold in knowledge management and CoPs are the key to unlocking this hidden treasure”. Wenger [WEN 98] defines CoP as a group of people who share a concern, a set of problems or a passion about a topic and who deepen their knowledge and expertise in this area by interacting on an ongoing basis. It is distinguished by three essential characteristics: a joint enterprise, a mutual commitment and shared repository/capital [WEN 02]. On the one hand and in the broadest sense, Correa et al. [COR 01] consider any community as a KC where members share knowledge (tacit or explicit) around an interest, a practice or a project activity. On the other hand, Cummings [CUM 03] posits that knowledge sharing is the means by which an organization obtains access to its own and other organizations’ knowledge. In the case of these communities, Bresman et al. [BRE 99] argued that individuals will only participate willingly in knowledge sharing once they share a sense of identity (or belonging) with others. This sense of identity is one of the several key factors to reach maturity for a community.

In the context of this research, we define community maturity as a community’s maximum capability to manage knowledge where community members actively interact/participate and effectively collaborate, reach mutual commitment based on a well-shared capital and adjust their efforts and behaviors in fulfilling the community mission by producing high-quality outcomes.

Recently, a number of maturity models related to KM have been proposed: the GKMMM [PEE 06] is descriptive and normative. It describes the important characteristics of an organization’s KM maturity level and offers Key Process Areas that characterize the ideal types of behavior that would be expected in an organization implementing KM. The KMAP [GAL 08] is based on the qualitative GKMMM [PEE 06] and Q-Assess developed by Science Applications International Corporation (SAIC). Q-Assess represented 12 subassessments to assess levels of maturity across three KPAs: people, processes and technology. This model allows assessing workgroups, and it highlights weaknesses and gives recommendations to deal with them. The MGKME [GRU 08] is composed of two levels: the underlying level and the operating level. Under eachcategory, many key issues are focused upon and addressed in the assessment process. They consist of managerial guiding principles, ad hoc infrastructures, generic KM processes, organizational learning processes, and methods and supporting tools. The KNM [HSI 09] is developed in order to navigate the KM implementation journey. This maturity model consists of two frameworks, namely: evaluation framework and calculation framework. The first one addresses three management targets: culture, KM process and information technology. The second one is characterized by a four-step algorithm model.

Each of the above maturity models deals with KM evaluation within organization; thus, it correlates maturity levels only with KM evolution stages and do not deal with many characteristics of communities: common values, sense of identity, history, etc. These models are not intended to assess communities in an informal mode in intra- or inter-organizational setting, even less in a holistic manner from a KM perspective. They address, more specifically, a formal project mode context in intra-organizational setting. Many of these models are descriptive and normative (e.g. GKMMM and MGKME), they do not prescribe or present actions to perform in order to address weaknesses revealed by the model.

Very few maturity models related to communities have been proposed. First, the community evolution model proposes five main stages as community maturity levels, which are potential, building, engaged, active and adaptive [GON 01]. For each of these stages, they defined fundamental functions and used three perspectives in order to describe the characteristics of every maturity stage. These perspectives are the behavior of people, degree and type of process support, and types of technology encountered at each stage. Second, the maturity model presents four stages of maturity (building, growth, adaptive and close) [LEE 10]. This model gives a snapshot of the current community maturity level based on a set of critical success factors, analyzes the stage and proposes a guide for improving the CoP. These maturity models are not all knowledge-oriented per se. Most are inspired from the five-staged CMM model without trying to focus on the originality of communities and to develop a maturity model that fit exactly with them. These models aim to assess communities in an intra-organizational context under a set of characteristics related to maturity stages. Furthermore, based on these models, we cannot differentiate a community from a social network or even a project team. Moreover, these models may not be generalized on different types of community since they focused mainly on CoPs.

Table 1.1. Comparison of CoMM with other maturity models

The main objective of the study reported in this chapter is to present the blueprint for a new CoMM based on the literature, which addresses some of the limitations described earlier. This prescriptive model is sufficiently generic to be applied to all types of communities and networks. It aims to assess the KM maturity of a given community holistically. F...