- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

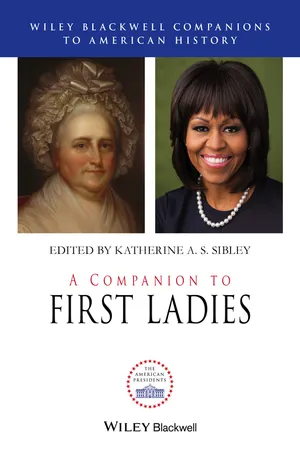

A Companion to First Ladies

About this book

This volume explores more than two centuries of literature on the First Ladies, from Martha Washington to Michelle Obama, providing the first historiographical overview of these important women in U.S. history.

- Underlines the growing scholarly appreciation of the First Ladies and the evolution of the position since the 18th century

- Explores the impact of these women not only on White House responsibilities, but on elections, presidential policies, social causes, and in shaping their husbands' legacies

- Brings the First Ladies into crisp historiographical focus, assessing how these women and their contributions have been perceived both in popular literature and scholarly debate

- Provides concise biographical treatments for each First Lady

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Companion to First Ladies by Katherine A.S. Sibley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Historia & Historia de Norteamérica. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

Martha Washington

Robert P. Watson

Martha Dandridge Custis, a native Virginian born in 1732, was the wife of George Washington. In that capacity she became the nation’s first “first lady.” She also distinguished herself as a gifted and gracious hostess for the young republic’s political affairs, her husband’s trusted confidante, and a beloved symbol of the American Revolution.

Young Martha

Martha Dandridge was the first of eight children born to John Dandridge (1701–1756) and Frances Jones Dandridge (1710–1785) of New Kent County, Virginia. Three brothers and four sisters followed, the last being born in 1756, when Martha was in her mid-twenties and already a wife and a mother with young children of her own. According to the family Bible, she was born on June 2, 1731 at the family’s two-story home known as Chestnut Grove. Martha appears to have had a normal and happy upbringing. However, few records and no personal letters of hers from that time have survived through history (Brady, 1996; Fields, 1994).

The Dandridge family lineage can be traced back to the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, when they were living in Oxfordshire, England. Surviving records from that time suggest that most of the Dandridge men in England made their living by farming and that several of the men in the family prospered. Documents also show that the first of Martha’s ancestors to cross the Atlantic Ocean were William Dandridge and his younger brother John, who came to America in 1715 (Fields, 1994). The two Dandridge boys made their new home in the Crown’s Virginia Colony, where they succeeded as merchants. They also wisely acquired vast land holdings in the eastern part of the colony and added to their wealth through the subsequent lease and sale of these properties.

The younger son, John, married Frances Jones, who had been born in the colonies and whose family included a line of well-respected preachers and religious leaders. Her ancestors hailed from England and Wales. One of them, Reverend Rowland Jones, grandfather of the woman whom John Dandridge married, appears to have been the first Jones to settle in the New World after sailing from Wales. Reverend Jones established a successful ministry in Virginia and his family, much like the Dandridge boys, was part of the new, landed class of colonists (Watson, 2002). Later on John Dandridge and Frances Jones would have a daughter named Martha, who would one day become the first lady of the United States of America.

Martha’s father, John, held several jobs and also served as county clerk. He owned a successful plantation on roughly five hundred acres near the Pamunkey River in the Tidewater region of eastern Virginia, which is where his daughter Martha was raised. On the basis of the few surviving records, scholars have suggested that the Dandridge family was not in the upper echelon of Virginia’s elite. Rather it could be considered as part of the colony’s “lesser aristocracy” (Anthony, 1990; Fields, 1994).

Because of the location of the family home, the family’s relative affluence, and her father’s public position, Martha likely met members of Virginia’s ruling families during her formative years, for example when they attended important social functions at the governor’s palace in Williamsburg, the colonial capital and most important social and political town in the region. It also appears that the Dandridges hosted neighbors and leading families at their home. Thanks to these opportunities, Martha would have been exposed from an early age to politics and to the social norms of entertaining. Of course, these were skills that would come in handy later in life when she served as first lady. She also participated in a débutante’s “coming out” event, something that was common in the colony among fifteen-year-old daughters of prominent parents with “aspirations” (Anthony, 1990; Bryan, 2002: 38).

Miss Dandridge’s childhood and teenage years were likely normal for a girl in a family with the social standing of the Dandridges. There are some clues as to her earliest experiences as a child and as a teenager. For instance, it is almost certain that she would have assisted her mother and others in hosting dinner parties and social galas, thereby developing skills as a homemaker. Martha knew how to cook and sew, and she acted with the social graces expected of a young woman of means in the colonial era. As an adult, she was a talented cook and a skilled hostess (Anthony, 1990; Watson, 2002). Her education would also have been one based on domesticity. This practical education was supplemented by lessons in music and dancing, likely from visiting tutors, and by exposure to the teachings of the Anglican Church (Anthony, 1990; Watson, 2002). As an adult, Martha was an active churchgoer, an avid reader of the Bible, and a religious, but not pious woman.

Mrs. Washington enjoyed literature and was a prolific letter writer, traits she likely fashioned as a child. However, she was an inconsistent speller—she spelled phonetically. This feature caused her some embarrassment during George Washington’s military and political career. During her married life, Mrs. Washington was also a practitioner of homeopathic medicine. She kept a book of home cures she relied on when friends and family members were taken ill. The tragic loss of her children and other loved ones would contribute to Martha’s behaving much like a hypochondriac. For instance, she discussed matters of health in many of her surviving letters and she worried about every sneeze and cough. More adventurous as a teenager, Martha developed great skill on horseback. She abandoned riding later in life, perhaps on account of the weight she gained, but she always enjoyed carriage rides (Brady, 1996; Watson, 2002).

Mrs. Custis

As a teenager, Martha Dandridge likely had several suitors on account of her family’s social status. She was described as being of average physical attractiveness, with almond-shaped, hazel eyes, medium-brown hair, and a soft, round face (Anthony, 1990; Watson, 2002). Standing roughly five feet in height, Martha was thin as a young woman. A computerized “age-regression” of an existing portrait—a version of which now hangs in Mount Vernon—has confirmed her former svelte visage (Farr, 2012). The more recognizable plump, matronly physique and demeanor identified with her in her later years appear to have come about around the time of motherhood, as evidenced by surviving portraits and letters. Paintings of the mature woman represent someone who seems reluctant to “sit” for the artist. She was a private individual who did not like being the focus of an artist’s brush. As a result, in the paintings Martha stares blankly back at the viewer, often wearing her signature white bonnet, which was somewhat fashionable for women of the time (Watson, 2000b).

Martha’s father, John Dandridge, was an elder at St. Peter’s Church, where the Dandridges were active members. This connection to the church made possible her first marriage. Also serving as a deacon at St. Peter’s was Daniel Parke Custis. It appears that Martha first caught Custis’s attention when she was only seventeen, although he likely knew her from the time she was a child. Twenty years Martha’s senior, Custis was born in 1711 and was heir to one of the colony’s largest tobacco plantations. One of the most eligible bachelors in the colony, Custis had never married and was thirty-nine when he wed John Dandridge’s nineteen-year-old daughter.

Little is known about the courtship (Fields, 1994: 421, 430, 434), but Daniel’s father (also a John) was initially opposed to the union. John Custis, a difficult and temperamental man, believed that his son would be marrying well below the family’s social standing. Virginia was perhaps the colony most conscious of social class, and such marital concerns among its elite were not uncommon. Moreover, the elder Custis had derailed his son’s earlier plans to marry other women, and for similar reasons (Brady, 1996). The details are vague, but it is known that John Custis ultimately changed his mind about the wedding after meeting the teenager, which suggests that Martha was a confident and impressive young woman (Watson, 2002). The couple married in 1750 at the Custis home, which was located roughly thirty miles from Williamsburg and was known ironically as “the White House.”

As the wife of a tobacco heir, Martha enjoyed a comfortable and affluent home life. However, her marriage was filled with hardships. One of them was motherhood. The young bride had four children over a period of less than six years. The children were Daniel Parke (1751–1754); Frances Parke (1753–1757); John Parke (1754–1781), nicknamed “Jacky”; and Martha Parke (1756–1773), known as “Patsy.” Tragically, Martha’s first two children died in infancy, Frances when Martha was pregnant with John and Daniel a few months later, during the year in which John was born. To make matters worse, Martha’s own father died in 1756—the year in which her last child, the one named after her, was born. In the following year her husband, who had often struggled with health issues, passed away. After just eight years of marriage, Martha had given birth to four children, buried two of them, and lost her father and her husband. She was only twenty-six at the time.

There was little time for mourning. The Custis widow had two infant children at home. She was also responsible now for the large and lucrative Custis estate and plantation. During the difficult years when she was still married, her father-in-law also died. Because her husband had no living siblings, she was now the sole heir to the family tobacco fortune. Not only was she confronted with the management of several large homes, the plantation, and the many slaves owned by the Custis family, but a long-running, complicated, and potentially ruinous lawsuit hung over the Custis business. The legal matter came to the fore after Daniel Custis’s death (Anthony, 1990; Brady, 1996). The fact that Daniel Custis did not leave behind a will and had not resolved the lawsuit suggests that he died suddenly and unexpectedly.

Martha nevertheless demonstrated great business acumen in dealing with the will, the lawsuit, and operations on the plantation. Some surviving letters reveal that the widow hired some of the leading attorneys and politicians in Virginia to represent her (Fields, 1994: 29–31, 54, 437; Watson, 2000b). The lawsuit was resolved to her satisfaction and, under Martha’s guidance, an extensive plantation with thousands of acres of land, several buildings, and a large workforce thrived. She also wisely decided to continue correspondence and business relations with her late husband’s partners and representatives, both in Virginia and in England. In one letter she notified a group of London merchants associated with Daniel:

I take the Opportunity to inform you of the great misfortune I have met with in the loss of my late Husband … As I now have the Administration of his Estate and the management of his Affairs of all sorts I shall be glad to continue the correspondence which Mr. Custis carried on with you.(Fields, 1994: xx)

Domestic Tranquility

Like Daniel Custis, George Washington, too, probably knew Martha well before they married, although no firm documentation exists on the matter (Fields, 1994: 445, 447). The two young Virginians lived not far from each other, were of roughly the same age (she was one year his senior), and likely attended some of the same social events in Williamsburg during the popular winter social season (Watson, 2000b). However, she was much higher on the social scale than Washington, whose father died when he was young and who lacked the advantage of a higher education or opportunity to travel.

As a young military officer, Washington was highly ambitious and the prospects of marrying a wealthy, established woman would have attracted him (Anthony, 1990). Indeed, as a young man Washington had unsuccessfully attempted to court daughters of prominent families. He also nurtured an infatuation with an older, wealthy woman named Sally Cary Fairfax, who happened to be married to one of his neighbors (Brady, 1996). For her part, it is probable that Martha, on account of social norms and gender roles of the time, would have been eager to remarry rather quickly. It would help to have someone who could manage the estate and business and could serve as a father to her young children.

Unfortunately no letters survive about their courtship (Fields, 1994). Many years later, however, Martha’s grandson, George Washington Custis, did tell the story of how the two met in 1758 (Watson, 2002). According to his account, Washington, a young colonial military officer at the time, was traveling to Williamsburg on business when he stopped to rest and water his horse near the home of a prominent neighbor and associate of the Custis widow by the name of Chamberlayne. Washington was invited to dine at the Chamberlayne home but declined, invoking the urgency of getting to Williamsburg for a meeting of great importance to his career. However, the young officer changed his mind when Chamberlayne informed him that his house gues...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Table of Contents

- Notes on Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter One: Martha Washington

- Chapter Two: Abigail Adams

- Chapter Three: Martha Jefferson Randolph, First Daughter

- Chapter Four: James and Dolley Madison and the Quest for Unity

- Chapter Five: Elizabeth Monroe

- Chapter Six: A Monarch in a Republic

- Chapter Seven: Rachel Donelson Robards Jackson

- Chapter Eight: Angelica Singleton Van Buren, First Lady for a Widower

- Chapter Nine: The Ladies of Tippecanoe, and Tyler Too

- Chapter Ten: Sarah Polk

- Chapter Eleven: Margaret Taylor, Abigail Fillmore, and Jane Pierce

- Chapter Twelve: Harriet Rebecca Lane Johnston

- Chapter Thirteen: Mary Todd Lincoln

- Chapter Fourteen: Eliza McCardle Johnson and Julia Dent Grant

- Chapter Fifteen: Lucy Webb Hayes, Lucretia Rudolph Garfield, and Mary Arthur McElroy

- Chapter Sixteen: Rose Cleveland, Frances Cleveland, Caroline Harrison, Mary McKee

- Chapter Seventeen: Ida McKinley

- Chapter Eighteen: Edith Kermit Carow Roosevelt

- Chapter Nineteen: Helen Herron Taft

- Chapter Twenty: Ellen Axson Wilson

- Chapter Twenty One: Edith Wilson

- Chapter Twenty Two: Florence Kling Harding

- Chapter Twenty Three: Grace Coolidge

- Chapter Twenty Four: The Historiography of Lou Henry Hoover

- Chapter Twenty Five: Anna Eleanor Roosevelt

- Chapter Twenty Six: Eleanor Roosevelt

- Chapter Twenty Seven: Elizabeth Virginia “Bess” Wallace Truman

- Chapter Twenty Eight: Overrated Pleasures and Underrated Treasures

- Chapter Twenty Nine: Jacqueline Kennedy

- Chapter Thirty: Lady Bird Johnson

- Chapter Thirty one: An Unlikely First Lady

- Chapter Thirty Two: Betty Ford

- Chapter Thirty Three: Eleanor Rosalynn Smith Carter

- Chapter Thirty Four: Nancy Reagan

- Chapter Thirty Five: Barbara Pierce Bush

- Chapter Thirty Six: Barbara Pierce Bush

- Chapter Thirty seven: Hillary Rodham Clinton

- Chapter Thirty Eight: Laura Welch Bush

- Chapter Thirty Nine: First Lady Michelle Obama

- Chapter Forty: First Lady Michelle Obama

- Index

- End User License Agreement