- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Psychology of Interpersonal Violence

About this book

The Psychology of Interpersonal Violence is a textbook which gives comprehensive coverage of interpersonal violence — exploring the various violent acts that occur between individuals in contemporary society.

- Examines in detail the controversial use of corporal punishment

- Explores ways that psychology can add to our understanding of interpersonal violence

- Offers directions for future research that can help to prevent or reduce incidents of interpersonal violence

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Psychology of Interpersonal Violence by Clive R. Hollin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psicologia & Psicologia forense. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Interpersonal Violence

Violence is a part of all our everyday lives. We read about violence in our morning newspaper, we hear about it in the daily news on the radio and television. We read murder mysteries for fun and play computer games that involve mayhem and death. Krug, Mercy, Dahlberg, and Zwi (2002) make the observation that “About 4400 people die every day because of intentional acts of self-directed, interpersonal, or collective violence. Many thousands more are injured or suffer other non-fatal health consequences as a result of being the victim or witness to acts of violence” (p. 1083). The accompanying costs are played out in the short-term costs of treating victims and helping families while the longer-term costs may be felt by victims whose lives are irrevocably changed and by the costs incurred in bringing the aggressor to justice.

We also know that violence comes in many shapes and forms. A report published by the World Health Organization (WHO; Krug et al., 2002) refers to three distinct classes of violence: first, self-directed violence as with suicide and self-harm; second, interpersonal violence, which is taken to be physical or sexual violence against a family member, a partner, or within the broader community; and third, collective violence in the sense of violent acts by large groups of people or by states such as so-called ethnic cleansing, terrorism, and war.

It is the second of the WHO classes of violence, interpersonal violence, which is of concern here.

What exactly is meant by the term interpersonal violence? “Interpersonal” can be understood in its literal sense to mean between people; however, “violence” is a little more problematic. The word “violence” is often used interchangeably with “aggression”. However, aggression is not the same as violence and it is used differently according to context. In everyday use we use aggression as an adjective to help describe certain forms of behaviour: we may say that a football team has an aggressive style of play, which is very different to saying a team has a violent style of play. In ethology the term “aggression” may be used in the sense of an instinct which, given the right environmental stimuli, leads to fighting between members of the same species (Lorenz, 1966). Tinbergen’s (1948) famous study of the three-spined stickleback provides an example of instinctive aggression. Tinbergen showed that when a male stickleback is faced with a strange male intruding into its territory, it is the perception of the intruder’s red colouration which is the key stimulus that releases aggression in the territorial male. It seems that at some seaside resorts (I took the picture below near Filey in Yorkshire) the birdlife has become overly aggressive.

It is possible that, like sticklebacks, humans have evolved to possess an aggressive instinct that may help explain human conflict (LeBlanc & Register, 2003). However, unlike sticklebacks, for humans there are the complicating factors of the powerful influence of previous learning together with our cognitions in the form of appraisals of the situation and our personal intentions. Siann (1985) is helpful with the suggestion that with respect to interpersonal transactions the term “aggression” refers to the intention to hurt another person but without necessarily causing any physical injury. In a similar vein, Anderson and Bushman (2002) state that “All violence is aggression, but many instances of aggression are not violent. For example, one child pushing another off a tricycle is an act of aggression but is not an act of violence” (p. 29). This latter view suggests a continuum that stretches from aggression at one end to violence at the other: Anderson and Bushman suggest the tipping point from aggression to violence is reliant upon the associated level of harm: “Violence is aggression that has extreme harm as its goal (e.g., death)” (p. 29).

Yet further, an important distinction may be drawn between reactive aggression and proactive aggression (sometimes called hostile aggression and instrumental aggression respectively). The term “reactive aggression” refers to impulsive acts of violence in which the aggressor’s psychological state is dominated by a negative affect such as anger. On the other hand, “proactive aggression” refers to premeditated acts of violence, typically carried out to achieve a personally satisfying goal such as financial gain or revenge (Polman, Orobio de Castro, Koops, van Boxtel, & Merk, 2007). As Babcock, Tharp, Sharp, Heppner, and Stanford (2014) point out, the terms “impulsive violence” and “premeditated violence” are also in use, with some overlap with reactive and proactive. The reactive/proactive distinction will be used here, acknowledging that other terms may carry similar if not identical meanings.

Thus, we can arrive at the understanding, as used in this text, that interpersonal violence is the direct, often face-to-face, actions of an individual, including acts of neglect, which inflict emotional, psychological, and physical harm on other people. These acts of violence may be carried out with premeditation or in the heat of the moment.

The complexity of violence has led to various theories from disciplines ranging from anthropology to zoology (Mider, 2013). However, an overview of contemporary psychological accounts of interpersonal violence provides the starting point here.

Psychological Accounts of Interpersonal Violence

There are several theoretical models with a psychological emphasis which have been formulated to provide an account of interpersonal violence. These various models seek to explain acts of interpersonal violence by drawing together in a cogent way a variety of psychological and social factors. In addition, there is a range of biological factors, although these are typically associated with aggression generally rather than interpersonal violence specifically (e.g., Farrington, 1997; Olivier & van Oorschot, 2005; Tiihonen et al., 2010; Umukoro, Aladeokin, & Eduviere, 2013).

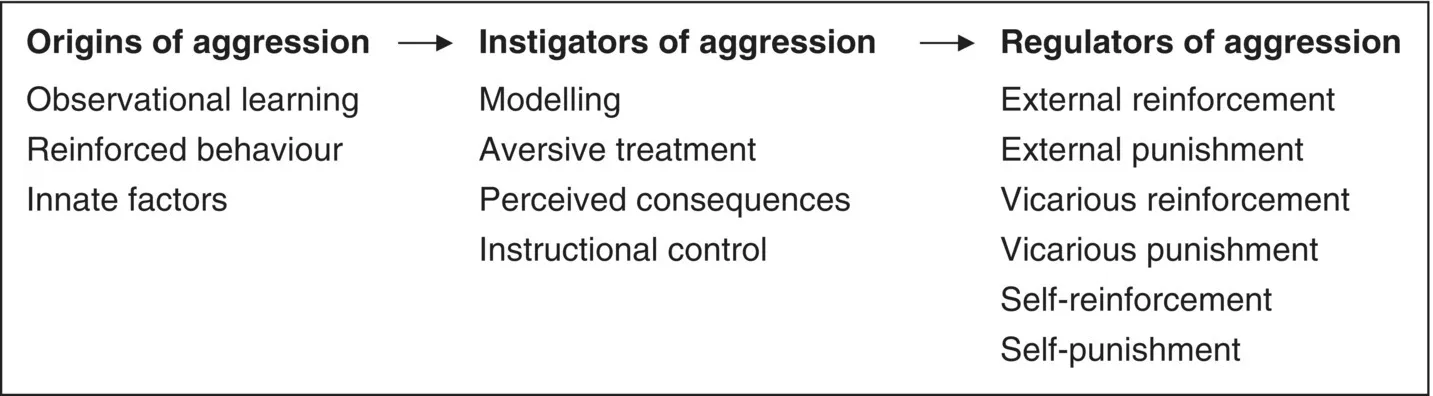

In the first psychological model, shown in streamlined form in Figure 1.1, Bandura (1978) describes a tripartite system, based on social learning theory, that relates to the origins, instigators, and regulators of aggressive behaviour.

Figure 1.1 Bandura’s Social Learning Model of Aggression.

Source: After Bandura, 1978.

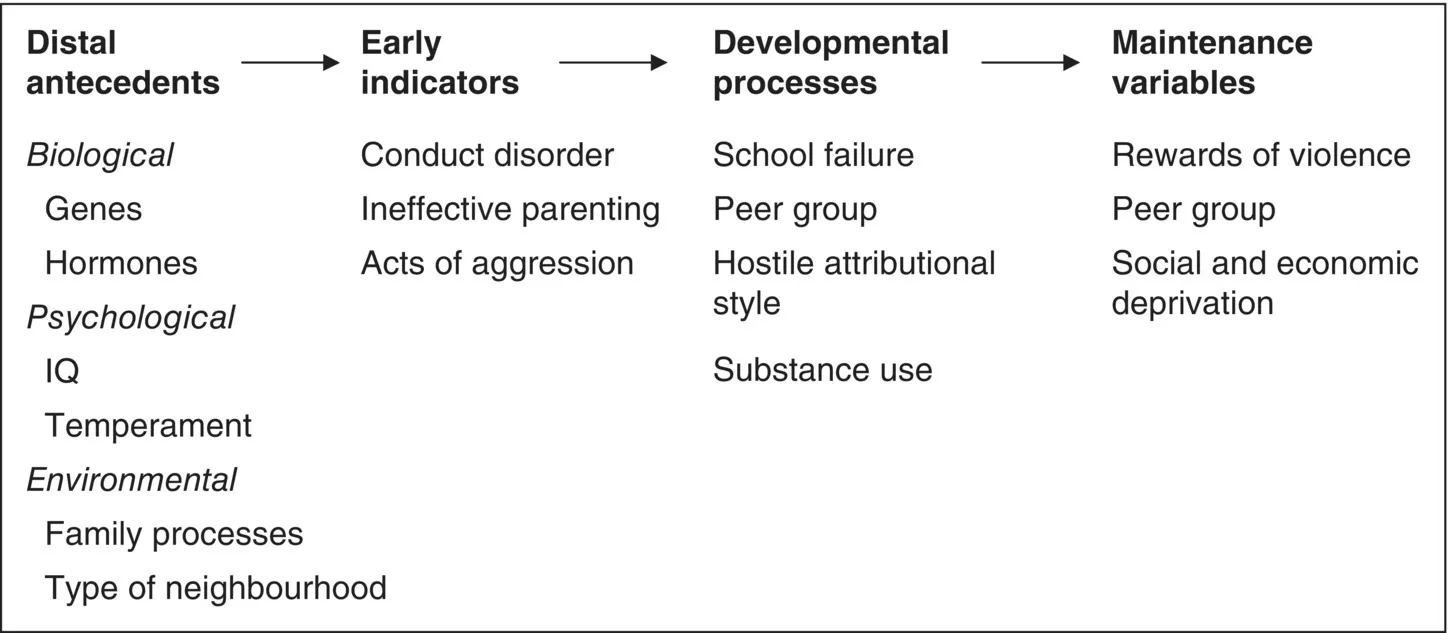

The model of the aetiology of violent behaviour presented by Nietzel, Hasemann, and Lynam (1999), also drawing on behavioural theory, describes four stages in the development and maintenance of violent behaviour. As illustrated in Figure 1.2, this model progresses through the lifespan identifying the various types of biological, psychological, and social risk factors which may be present at different times.

Figure 1.2 Developmental Model of Violence.

Source: After Nietzel et al., 1999.

There is, not surprisingly, a reasonable degree of overlap between these two models: for example, Bandura’s innate factors are congruous with Nietzel et al.’s biological antecedents, while the importance given by Bandura to reinforcement as a regulator of behaviour is mirrored in Nietzel et al.’s maintenance variables. As noted by Nietzel et al., the evidence base for the importance of the different variables is varied in strength, as is the evidence for the strength of relationships between the variables both within and across stages. Finally, there may be more than one pathway through the model so that individual differences in constitution and experience produce several combinations of variables which may be important in different circumstances.

The General Aggression Model (GAM), as formulated by Anderson and Busman (Anderson & Bushman, 2002; DeWall, Anderson, & Bushman, 2011), places an emphasis on the individual taking part in a social interaction that culminates in a violent act. The GAM views social interactions as a sequence of exchanges, each of which is termed an episode, involving verbal and nonverbal behaviour. The main components of the GAM, not unlike other models, consist of inputs from the person and the situation, the person’s internal affective and cognitive state which is the route through which the input information is processed, and finally the outcomes of appraisal and the nature of the individual’s decision on how to act.

These psychological models all highlight the importance of three, interconnected, areas: first, the formative factors in an individual’s development which are associated with the likelihood of violent conduct; second, the environments in which violence occurs; and third the psychological and social processes which occur during the act of violence. However, before looking at these three areas in more detail, there is one more variable to consider, the gender of the violent person.

Gender

Inspection of the criminal statistics reveals that there is a gender divide as far as crime, including violent crime, is concerned (Ministry of Justice, 2010a). It is clear from the criminal statistics that men are significantly more involved in crime, including violent crime, than women. However, while a man or a woman may be convicted of the same violent crime, it does not follow that the factors associated with the development and maintenance of that violent act are identical for men and women (Collins, 2010; Putallaz & Bierman, 2004). It is likely that there are some background factors, such as poverty and harsh parenting, which are common to violent men and to violent women, and some gender-specific factors such as prosocial attitudes and emotional problems (Hollin & Palmer, 2006; Manchak, Skeem, Douglas, & Siranosian, 2009).

Crick and Grotpeter (1995) suggest that there is a relationship between gender and type of violence. They note that research typically finds that male children use physical aggression to a degree not seen in female children. However, they make the point that just because young girls do not hit, the assumption cannot be made that they are not aggressive; rather, the aggression may take forms other than hitting. Crick and Grotpeter note in support of their hypothesis that girls’ aggression is often relational rather than physical: relational aggression is characterised by attempting to harm other children by damaging their friendships, excluding them from social activities and social groupings, and by spreading false stories so leading to the child’s rejection by other children.

Cross and Campbell (2011) make a similar point about older age groups: men are more likely than women to use severe forms of violence such as kicking and punching which inflict physical injury. When the form of violence shifts to less physically aggressive acts, such as hurtful gossip and persistent teasing, so the gender difference is lost. An American study reported by Zheng and Cleveland (2013) compared the developmental trajectories of young men and women, aged between 15 and 22 years, with regard to acts of both violent and non-violent delinquency. They reported that at lower levels of delinquency there were only minimal variations in delinquency between the genders. However, at the higher levels of delinquency, which Zheng and Cleveland called chronic, the delinquent acts were violent in ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- 1 Interpersonal Violence

- 2 “Everyday” Violence

- 3 Violence at Home

- 4 Criminal Violence

- 5 Sexual Violence

- 6 Where To Next?

- References

- Index

- End User License Agreement