- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Lepidoptera and Conservation

About this book

The third in a trilogy of global overviews of conservation of diverse and ecologically important insect groups. The first two were Beetles in Conservation (2010) and Hymenoptera and Conservation (2012). Each has different priorities and emphases that collectively summarise much of the progress and purpose of invertebrate conservation.

Much of the foundation of insect conservation has been built on concerns for Lepidoptera, particularly butterflies as the most popular and best studied of all insect groups. The long-accepted worth of butterflies for conservation has led to elucidation of much of the current rationale of insect species conservation, and to definition and management of their critical resources, with attention to the intensively documented British fauna 'leading the world' in this endeavour.

In Lepidoptera and Conservation, various themes are treated through relevant examples and case histories, and sufficient background given to enable non-specialist access. Intended for not only entomologists but conservation managers and naturalists due to its readable approach to the subject.

Much of the foundation of insect conservation has been built on concerns for Lepidoptera, particularly butterflies as the most popular and best studied of all insect groups. The long-accepted worth of butterflies for conservation has led to elucidation of much of the current rationale of insect species conservation, and to definition and management of their critical resources, with attention to the intensively documented British fauna 'leading the world' in this endeavour.

In Lepidoptera and Conservation, various themes are treated through relevant examples and case histories, and sufficient background given to enable non-specialist access. Intended for not only entomologists but conservation managers and naturalists due to its readable approach to the subject.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Lepidoptera and Invertebrate Conservation

Introduction

Lepidoptera, the butterflies and moths, have for long been familiar both to naturalists and people in many other walks of life. Butterflies, arguably the most popular of all insect groups, have been a major focus for collectors and other hobbyists, as symbols of the wealth and health of the ecosystems that support them – and those interests have also contributed to concerns arising from their declines and, in a few cases, well publicised extinctions. The clearly documented losses of taxa such as the Large copper (Lycaena dispar dispar) from the fens of eastern England in the mid nineteenth century (Duffey 1977, Feltwell 1995) and reported decline of the Xerces blue (Glaucopsyche xerces) a decade or so later in the western United States (where it became extinct later: Pyle 2012), for example, each mark the beginnings of concern for insect conservation in those regions. More widely, the popularity of butterflies and later extinctions (such as of yet another lycaenid, the Large blue, Maculinea arion, in Britain as recently as 1979: Thomas 1991) have led to studies on these insects forming the strongest foundation of the developing science of insect conservation. Several factors contribute to this – simple aesthetics are important in creating a liking and sympathy for conspicuous insects, whether they are tiny lycaenids, as the above cases, or large and spectacular tropical swallowtails or birdwings (Papilionidae) such as those that enthralled explorers of then remote parts of the world during the Victorian era, and continue to do so. That era saw the proliferation of natural history documentation, prompted in part through the ‘philatelic approach’ to collecting, with progressive accumulation of distribution records, biological and life history details. These interests induced production of increasingly complete and sophisticated illustrated handbooks that enabled hobbyists to identify their study objects with reasonable certainty and summarise biological and distributional information, and so to confidently contribute further to the record of fact and inference that has provided a vital legacy to present-day students. This legacy is geographically biased, of course, but the 200 years and more of accumulated information has rendered the butterflies of Britain, followed by those of some other parts of the northern temperate zones, the best documented of all regional insect faunas. In short, they are informative as examples and models for emulation and understanding to biologists seeking a foothold in the daunting world of invertebrate diversity. Importantly, they are accessible to non-specialists, encouraged by the wealth of well illustrated identification guides and authoritative but non-technical information available.

Butterflies are unusual, also, in their cultural connotations, with artistic roles since pre-Columbian years (Pogue 2009) including representation in the ancient art from many parts of the world, as well as presence in literature, myth and religion – the latter including symbolised connection to the soul in several distinct cultures. That, in general, people ‘like butterflies’ and do not fear them as harmful renders them popular and powerful ambassadors for the wealth of insect life. However, there is also suggestion that the appeal of such insects may link to ‘academic disapproval’ and deter young scientists from taking up study of the group. Study of such aesthetically pleasing insects is occasionally associated with second-rate intellect, so that supervisors may lead potential lepidopterist graduate students to turn their focus to ‘insect taxa that are judged to be more academically respectable’ (Kristensen et al. 2007). Simplistically, butterflies, together with a few families of larger showy moths (notably hawkmoths, Sphingidae, and silk moths, Saturniidae) and the brightly coloured day-active burnets (Zygaenidae), are commonly regarded as ‘beginners' bugs’, simply because they are attractive and accessible easily by non-specialists. The reality is far different, as much recent literature – some cited in later chapters – demonstrates!

However, the butterflies are only a small component of one of the largest insect orders. They comprise only some 20,000 named species, a total surpassed by each of several individual families of moths which comprise, perhaps, a further 350,000 species. Powell (2003) estimated global Lepidoptera species richness as ‘certain to exceed 350,000 species’ with considerable uncertainty over what the real total may be, and rather more than 160,000 species having been named. These are distributed amongst about 124 families grouped into 47 superfamilies (Kristensen 1999). More recently, and incorporating the uncertainty implied here, Kristensen et al. (2007) estimated that ‘There are considerably more than a quarter-million Lepidoptera species, probably in the order of magnitude of half a million, but there are not a million – let alone several millions’. The theme of taxonomic diversity is revisited in Chapter 2, and is noted here simply to emphasise that we are dealing with an enormous group of insects – confidently amongst the four largest orders of insects as they are at present understood, and probably the smallest of the four – and amongst which biological and taxonomic knowledge is very uneven (Scoble 1992). Estimates of species numbers are difficult, not least because of the great variety of species concepts used in modern biology, and the transition from simple morphospecies to greater appreciation of intrinsic variation may affect the number of entities recognised very considerably.

Our confidence from studies on butterflies dissipates rapidly when confronted with our ignorance over many moths. The ‘accessibility’ of butterflies contrasts markedly with the confusions that flow from many small moths, and is coupled also with the very different image many people have of moths, as annoying, drab, nocturnal pests: each a sweeping generalisation to which there are many exceptions! The masterly introductory chapter to ‘Moths’ (Majerus 2002) gives much background to this dichotomy of perceptions. Progressive incorporation of moths to augment the conservation perspective founded in butterflies (Chapter 4) is enriching the themes underpinning much insect conservation and enlarging appreciation of the biological templates against which insect diversity can be appraised. Majerus (2002) ventured that, for Britain, the strong faunistic knowledge has rendered Lepidoptera the most suitable group for studying the impacts of anthropogenic changes on terrestrial fauna. Many others have expressed similar confidence.

Biological background

Lepidoptera are not an ancient order. Unlike the Coleoptera, accepted widely as the most diverse of all insect orders and which occur in the fossil record from the Permian era some 250 million years ago, Lepidoptera proliferated only in the Cretaceous period, developing and radiating in parallel with the flowering plants and so broadly ‘only’ about 100 million years old. The fossil record is very sparse: Kristensen and Skalski (1999) estimated that only 600–700 specimens of fossil Lepidoptera were then known, a high proportion of them in resins, and including Baltic amber as a major source. Although some fossils believed to be Lepidoptera occur nearly 200 million years ago in the Jurassic, the major lineages of the order seemingly developed much more recently. Details will continue to be refined as further evidence accumulates, as will how angiosperm development really fostered diversification of Lepidoptera (Powell 2009). However, the Lepidoptera constitutes perhaps the largest single evolutionary lineage adapted to depend on living plants (Powell & Opler 2009).

Those early coevolutions with angiosperms apparently founded the two major ecological roles associated with modern Lepidoptera. Many adult Lepidoptera feed on plant nectar, and collectively display a range of features that render many of them effective, and sometimes highly specific, pollinators. Larvae, caterpillars, of most Lepidoptera are chewing herbivores and, whilst most feed on or in foliage, particular taxa may exploit virtually any part of a plant. Lepidoptera are widely considered the most important insect group of defoliators. Many species are very specialised in feeding habit, and strict host plant specificity is common; that specificity may extend from plant taxon to tissue, growth stage, season, degree of exposure (sun or shade environments) and many other restrictions that may influence resource accessibility and suitability, and which must be considered in conservation management. The key realisation is simply that every species of Lepidoptera comprises two very different biological entities, with larva and adult disparate in form and habits; they occupy different habitats (commonly at different times of the year with little or no seasonal overlap) and exploit different resources, so have different ecological pressures and needs for conservation. For many species, the larva, although less often observed, is the dominant stage, far longer lived than the relatively transient adult stage. In essence, the two stages are ‘twin’ organisms and the needs of both are central to conservation. Those needs include, as examples, how adults track nectar sources for food and find suitable oviposition sites, and how larvae find and exploit plant or (rarely) other foods, withstand depredations of predators and parasitoids and later find suitable pupation sites. Adults may need to disperse actively, sometimes over large distances as seasonal migrants, with most caterpillars in contrast dispersing rather little from where they eclose. Intricate behavioural cues and ecological strategies and specialisations are rife amongst Lepidoptera, and understanding and heeding these is another important component of conservation. Activity of both stages is influenced strongly by temperature and a range of other environmental features, as well as the accessibility of key foodstuffs – often very specific – that have led to highly characteristic seasonal and spatial patterns of development. Dispersion of the key resources (Chapter 7) from local to landscape scales is thus a critical aspect of conservation, with many of the trophic associations long entrenched over evolutionary time.

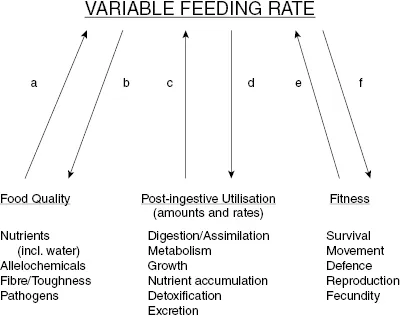

In common with many other insect herbivores, a particular obligatory food plant species may not always be suitable, but factors such as water or nitrogen content, exposure of the plant and presence of plant defensive chemicals influence local or seasonal exploitation. Figure 1.1 illustrates some of these constraints and, as Slansky (1993) commented, ‘For a caterpillar … feeding involves much more than merely filling its gut with the nearest available plant tissue’. However, it is commonplace for a suitable food plant species to be much more widely distributed than a specialist insect herbivore, and reasons for herbivore absence at places well within its range and dispersal capability are often anomalous. ‘Host quality’ factors affect plant suitability in time and space, and also influence incidence and abundance of the Lepidoptera (Dennis 2010).

Fig. 1.1 Interactions between feeding rate and food quality, food utilisation and fitness in insect herbivores: (a) food quality can affect feeding rate, and (b) feeding may affect food quality; (c) post-ingestive food utilisation can affect feeding rate, and (d) the converse; (e) fitness components may affect feeding rate, and (f) feeding affects fitness (Source: Slansky 1993. Reproduced with permission of John Wiley & Sons.).

Understanding these factors is critical in fine-scale conservation management, and their elucidation may involve very detailed study. The Sandhill rustic moth (Luperina nickerlii leechi, Noctuidae, Chapter 5, p. 51) is known only from one site in Cornwall, southern England, where caterpillars are associated with sand couch-grass (Elytrigia juncea). There are large areas on the site where the plant occurs but the moth does not (Spalding et al. 2012). Luperina is associated with abundant host plant cover and high numbers of stems and rhizomes – but is also restricted to areas with bare ground and levels of disturbance, so that the suitability of the host plants represents ‘a fine balance between disturbance and vegetation condition’. Discussed in detail by Spalding et al. 2012, maintenance of suitable conditions involves attention to creating areas of bare ground with coarse shingle and extensive, vigorous patches of Elytrigia, and few other competing plants. Occasional disturbance may be beneficial, deterring establishment of competing vegetation.

Most present-day associations with host plant taxa are outcomes of long evolutionary associations (Powell et al. 1999), but many geographical gaps in knowledge persist, and much of the interpretation of host–plant relationships has arisen from northern temperate region studies. A key presumption in conservation is that natural associations involving native plants and native insects are the ideal target for sustainability. In other cases, however, alien plants (such as weeds or ornamentals) may be adopted as resources and add further, sometimes complex, dimensions to conservation management. Native Lepidoptera may ‘switch’ to utilise such alien hosts, which can become important components of the species' ecology – for example, as substitutes for natural hosts that have declined or been lost to development. Thus, in North America, the endan...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1: Lepidoptera and Invertebrate Conservation

- 2: The Diversity of Lepidoptera

- 3: Causes for Concern

- 4: Support for Flagship Taxa

- 5: Studying and Sampling Lepidoptera for Conservation

- 6: Population Structures and Dynamics

- 7: Understanding Habitats

- 8: Communities and Assemblages

- 9: Single Species Studies: Benefits and Limitations

- 10: Ex Situ Conservation

- 11: Lepidoptera and Protective Legislation

- 12: Defining and Alleviating Threats: Recovery Planning

- 13: Assessing Conservation Progress, Outcomes and Prospects

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Lepidoptera and Conservation by T. R. New in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Biology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.