Fracking

Further Investigations into the Environmental Considerations and Operations of Hydraulic Fracturing

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Fracking

Further Investigations into the Environmental Considerations and Operations of Hydraulic Fracturing

About this book

Since the first edition of Fracking was published, hydraulic fracturing has continued to be hotly debated. Credited with bringing the US and other countries closer to "energy independence, " and blamed for tainted drinking water and earthquakes, hydraulic fracturing ("fracking") continues to be one of the hottest topics and fiercely debated issues in the energy industry and in politics.

Covering all of the latest advances in fracking since the first edition was published, this expanded and updated revision still contains all of the valuable original content for the engineer or layperson to understand the technology and its ramifications. Useful not only as a tool for the practicing engineer solve day-to-day problems that come with working in hydraulic fracturing, it is also a wealth of information covering the possible downsides of what many consider to be a very valuable practice. Many others consider it dangerous, and it is important to see both sides of the argument, from an apolitical, logical standpoint.

While induced hydraulic fracturing utilizes many different engineering disciplines, this book explains these concepts in an easy to understand format. The primary use of this book shall be to increase the awareness of a new and emerging technology and what the various ramifications can be. The reader shall be exposed to many engineering concepts and terms. All of these ideas and practices shall be explained within the body. A science or engineering background is not required.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Chapter 1

Environmental Impact – Reality and Myth and Nero Did Not Fiddle While Rome Burned

- ongoing mistrust of data and findings due, in great part, to semantics, and

- by the industry initially refusing to disclose the chemical makeup of fracking fluids and the additives used to enhance hydraulic fracturing.

1.1 The Tower of Babel and How it Could be the Cause of Much of the Fracking Debate

Chapter 2

Production Development

- Tight Gas: Wells produce from regional low-porosity sandstones and carbonate reservoirs. The natural gas is sourced (formed) outside the reservoir and migrates into the reservoir over time (millions of years). Many of these wells are drilled horizontally, and most are hydraulically fractured to enhance production.

- Coal Bed Natural Gas (CBNG): Wells produce from the coal seams, which act as source and reservoir of the natural gas. Wells frequently produce water as well as natural gas. Natural gas can be sourced by thermogenic alterations of coal or by biogenic action of indigenous microbes on the coal. There are some horizontally drilled CBNG wells, and some that receive hydraulic fracturing treatments. However, some CBNG reservoirs are also underground sources of drinking water, and as such, there are restrictions on hydraulic fracturing. CBNG wells are mostly shallow, as the coal matrix does not have the strength to maintain porosity under the pressure of significant overburden thickness.

- Shale Gas: Wells produce from low permeability shale formations that are also the source for the natural gas. The natural gas volumes can be stored in a local macro-porosity system (fracture porosity) within the shale, or within the micro-pores of the shale or it can be adsorbed onto minerals or organic matter within the shale. Wells maybe drilled either vertically or horizontally, and most are hydraulically fractured to stimulate production. Shale gas wells can be similar to other conventional and unconventional wells in terms of depth, production rate, and drilling.

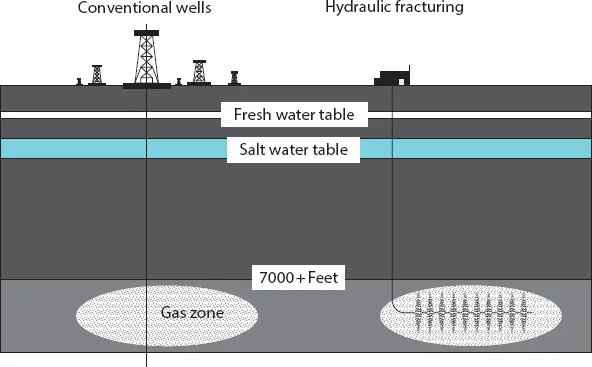

- An initial length of steel pipe, called conductor casing, is inserted into a vertical wellbore soon after drilling begins. This is done to stabilize the well as it passes through the shallow sediments and soils near the surface.

- Once conductor casing is set, operators continue drilling and insert a second casing, called surface casing, from the ground surface and extending past the depth of all drinking water aquifers.

- After allowing the cement behind the casings to set (cementing is described in detail in the following section), operators continue drilling for approximately 10 to 50 feet before stopping to test the integrity of the cement process by pressurizing the well.

- In horizontal wells, after drilling the horizontal section of the well, operators run a string of production casing into the well and cement it in place.

- Operators then perforate the production casing using small explosive charges at intervals along the horizontal wellbore where they intend to hydraulically fracture the shale.

- Acid stage; consisting of several thousand gallons of water mixed with a dilute acid such as hydrochloric or muriatic acid: This serves to clear cement debris in the wellbore and provide an open conduit for other frack fluids by dissolving carbonate minerals and opening fractures near the wellbore.

- Pad stage; consisting of approximately 100,000 gallons of slickwater without proppant material: The slickwater pad stage fills the wellbore with the slickwater solution (described below), opens the formation, and helps to facilitate the flow and placement of proppant material.

- Prop sequence stage; which may consist of several sub-stages of water combined with proppant material (consisting of a fine mesh sand or ceramic material, intended to keep open, or “prop,” the fractures created and/or enhanced during the fracturing operation after the pressure is reduced): This stage may collectively use several hundred thousand gallons of water. Proppant ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Preface

- List of Contributors

- An Introduction to Hydraulic Fracturing

- Chapter 1: Environmental Impact – Reality and Myth and Nero Did Not Fiddle While Rome Burned

- Chapter 2: Production Development

- Chapter 3: Fractures: Their Orientation and Length

- Chapter 4: Casing and Cementing

- Chapter 5: Pre-Drill Assessments

- Chapter 6: Well Construction

- Chapter 7: Well Operations

- Chapter 8: Failure and Contamination Reduction

- Chapter 9: Frack Fluids and Composition

- Chapter 10: So Where Do the Frack Fluids Go?

- Chapter 11: Common Objections to Drilling Operations

- Chapter 12: Air Emissions Controls

- Chapter 13: Chemicals and Products on Locations

- Chapter 14: Public Perception, the Media, and the Facts

- Chapter 15: Notes from the Field

- Chapter 16: Migration of Hydrocarbon Gases

- Chapter 17: Subsidence as a Result of Gas/Oil/Water Production

- Chapter 18: Effect of Emission of CO2 and CH4 into the Atmosphere

- Chapter 19: Fracking in the USA

- Appendix A: Chemicals Used in Fracking

- Appendix B: State Agency Web Addresses

- Bibliography

- Index

- End User License Agreement