![]()

1

Evolution of Wireless Sensor Networks

“What a heavy burden is a name that has become too famous”

– Voltaire

We have come quite far since cavemen utilized fire to detect lions approaching their caves. Fire, serving both as a deterrent and a detector (via resulting shadows), was one of man’s earliest sensing mechanisms. Thousands of years later, we have the technology to detect traces of pheromones, intrusion of malaria-mosquitoes, send biological sensors down the blood stream and report forest fires by harvesting power from the pH imbalance surrounding tree roots1. Not long after the emergence of wireless networks, practitioners integrated wireless tethering to deliver sensing into regions never thought possible; both in the extremities of the Earth, and within our own bodies.

Wireless sensor networks (WSNs) have evolved from many domains and due to various application demands. Today, the view of “what a WSN comprises” differs significantly, and is almost always a function of the domain of interest. Thus, WSN definitions are generally either vague or non-inclusive. It is misleading to tie definitions to WSN predecessors without context.

In this chapter we begin our journey with WSNs from their establishment, to current norms and commonalities in design. Hence, we address a developmental view, based on chronological advancements in telecommunications. Understanding what a WSN is, and the static nature of its initial propositions and design parameters, opens the door for the discussion of novel paradigms in WSNs; namely the topic of this book. We focus our discussions on paradigm shifts that render WSNs dynamic, both in operation and utility.

1.1. The progression of wireless sensor networks

First, it is important to note the static nature of many of the early designs and deployments of WSNs. In the mid-1990s the rise of mobile ad hoc networks (MANets) caused a stir in communications research and industry. Simply, being able to construct and utilize a wireless network on the go, without establishing a fixed topology or tending to its operation frequently, struck practitioners in this domain with significant ideas for advancements. A detailed overview of MANets and their pertinent challenges was presented by Chlamtac, Conti and Liu in [CHL 03]. Integrating MANets with sensors lead to the development of WSNs by the late 1990s.

The diversity of assumptions made on what a WSN comprises, resulted in a wide range of architectures that are dubbed sensor networks. However, they mostly maintain a number of properties; namely wireless communication, coordinated operation and reporting to sink(s). An intrinsic umbrella is to maintain energy efficient operation in all WSN protocols.

As WSN architectures and protocols evolved, their tasks extended beyond sheer reporting. Their complexity expanded many folds in the events to be detected, redundancy in reporting required, density of deployments, quality of data, coverage span and reliability. Significant control overhead resulted from mandating coordination, especially when driven by attempts to synchronize sensor node operation. More importantly, the advent of real-time sensing applications mandated that WSNs operate reliably under significant constraints of time and power consumption. A comprehensive survey on synchronization problems in WSNs is presented in [SUN 05] and highlights how a single requirement can significantly impact operational mandates of a WSN and increase its overhead without improving the quality of the data collected.

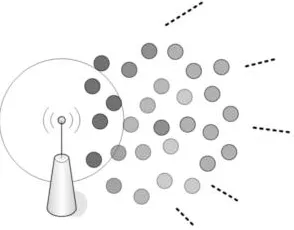

As our requirement for WSN coverage and geographical span grew, single-hop communication with the sink became impractical. The simple task of sensing and reporting – over multi-hop – resulted in bottlenecks of energy dissipation and time latency issues, demonstrated in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1. Typical energy and time latency bottlenecks around the sink in a multi-hop WSN. For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/oteafy/sensornetworks.zip

Thus, it was clear that the simple operation of sense, report and relay was not efficient for WSNs. Not only did it burden all nodes that detect an event with reporting it, but it increased overall traffic in the network and depleted its energy reservoirs at exponential rates. Accordingly, many approaches for duty cycling (having nodes sleep for a percentage of their lifetime to preserve power) emerged. Moreover, protocols attempting to relocate the sink, deploy multiple sinks and adapting sink power to cover a larger span of the network have emerged. Ultimately, arguments for bringing the data closer to the sink, or vice versa, dominated the literature on relocation for enhanced connectivity. Today, there is no single solution, and neither argument prevails. Realistically, as in most scenarios of WSNs, the deciding factor is the application at hand.

However, manipulating sink and node locations resulted in significant work on WSN deployment and mobility. Researchers attempted to study the effect of relocating nodes for improving coverage and connectivity, and the impact of error on each. A comprehensive study was presented in [XU 10]. A related field of study investigates the impact of placement on node operation, and how it could be incorporated in the design of the network. This is evident in arguments for deterministic node placement and random deployment; such as when thrown in the field from a plane (e.g. over volcanoes). An important aspect of node placement is deployment overhead. While grid-based deployments were long favored in research due to leverage in modeling and planning, realistically deployments were seldom grid-based.

As the case for random deployments became more prominent, researchers investigated the merit of dense deployments to assure feasible coverage. That is, since we are “throwing in” nodes to cover a given region, what is the cost-benefit analysis of throwing in more nodes to ensure that all the area required is indeed covered. Thus, significant research emerged on the impact of varying nodal density in random deployments. Arguments in support of dense deployments cited the value of redundancy in reports to achieve higher reliability, improving failure mitigation schemes as nodes are prone to faults, and prolonging network lifetime as we employ advanced duty cycling schemes. However, researchers have argued that improving the quality of nodes and ensuring minimalistic operational mandates – in addition to reducing the overhead of synchronizing duty cycles – would yield more efficient WSNs, especially as we avoid unnecessary contention over an already strained medium. Simply put, what we gain in reliability we lose in MAC contention and synchronization efforts, not to mention the cost of all the extra nodes.

To improve the node operation, attempts were made to study the effect of integrating redundant components on nodes in case some fail or for utilizing each component at the desired level of operation when needed. Others attempted to study the different operation levels within a single node, practically duty cycling its individual components instead of the node as a whole. This approach, along with others that opened up the view of a sensing node as a number of components, rather than a single black box, is the topic of the second core of this book.

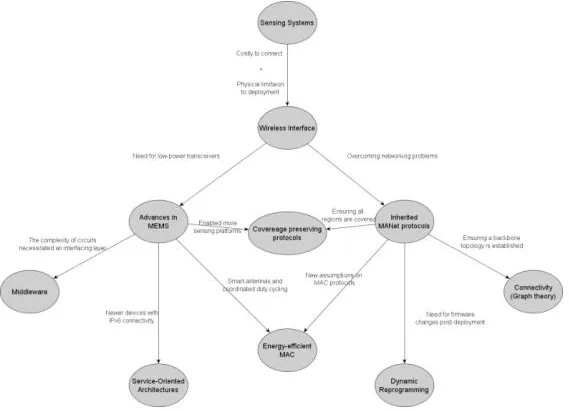

There are indeed many fields of research in WSNs. However, the general aim of improving functional capacity while maintaining energy efficient operation is predominant. In Figure 1.2, we highlight major domains of influence in the development of WSNs from its ancestors, and causalities that are evident in this field.

1.2. Remote sensing: in retrospect

Environmental phenomena and monitoring triggered the very first documented automated sensing system. Back in 1939, a pioneering attempt of monitoring weather conditions resulted in an autonomous weather station. It collected frequent samples, and was powered with gasoline; enough to sustain operation for four months. The operators at the time would visit the station at the end of the operational period to refuel and to retrieve the manifests of readings collected over the time [HAR 06].

Figure 1.2. Evolution of sensing systems and influence of related technologies

As early as that deployment, it was notable that environmental phenomena impose the most restrictive factors. The issue of accessing information was somehow mitigated by the introduction of remote satellite sensing in the 1970s. The first major project, named Landsat, has collected imagery over the years and been recognized as a vital database for researchers in many fields. After seven phases, Landsat 8 was launched into space in February 2013. More details about the utility and impact of the Landsat project are presented by Loveland, Cochrane and Henebry in [LOV 08b].

Other systems have adopted satellite communication to report the collected information from remote sites, yet major hindrances in lifetime and cost effectiveness of payload communication have deemed them infeasible in most scenarios. Such scenarios include monitoring wild life inhabitants, the physical impact of wind, rain, earthquakes and even abruptions of volcanoes. Many sensing systems remain wired to date due to the foreseen communication costs. However, current wired sensing systems are maintained mainly as a resilience measure for harsh environments. The notion of a WSN, which is as resilient as wired sensing networks is improving, with new designs specifically targeting harsh environments.

1.3. Inherited designs and protocols from MANets

Adopting an ad hoc topology for wireless communication has been a major implication for categorizing WSN under MANets. However, many of the properties shared between both types of network have inhibited the progression of WSNs. A major domain has been the substantial overhead of control messages exchanged. While nodes in MANets have the batteries to carry such a load (and are mostly rechargeable), WSNs are seldom equipped with enough power to coordinate their operation with neighboring nodes.

Many of the primary medium access control (MAC) schemes for WSNs were adopted from MANets. This was first spurred by the use of ALOHA-based systems, and subsequent collision resolution MAC protocols. Even more, collision avoidance protocols that spurred from wired networks, such as carrier sense multiple access (CSMA), that carried on to CSMA/CA (collision avoidance) and are widely adopted in MANets, have been utilized in early WSNs. However, the field of MAC protocols for WSNs reached saturation by the mid-2000s, and advancements in this field are mostly incremental. Interested readers may refer to the survey presented by Demirkol et al. in [DEM 06], and explore further details in the comprehensive survey by Naik and Sivalingam [NAI 04].

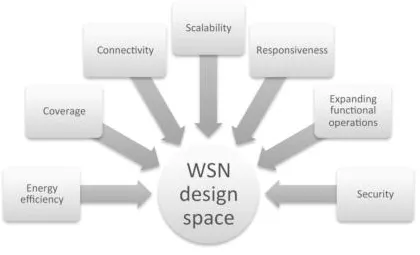

In general, the design space of WSNs varies significantly according to the application at hand. The current status quo is significantly diverse, resulting in a view that is equally disparate of what WSNs can do, and the protocols that govern their operation. However, the spectrum of design considerations for WSNs is consistently similar. In Figure 1.3, we present the major domains that encapsulate the design space of WSNs. While this depiction is not comprehensive, it represents the mainstream.

Figure 1.3. The fundamental design space of WSNs

1.4. Book outline

This book is organized under three cores. The first core addresses definitions and principles in WSNs, advancing through the history of sensing systems and how progression in mobile ad hoc networks (MANets) has aided the design and implementation of WSNs and more importantly, on the design and deployment aspects that render WSNs dynamic. We then emphasize two core phases. First, the middleware that supported WSN development and newer models that adopt light-weight operating systems for task allocation and resource management, in addition to the remote reprogramming paradigm that enables code redistribution. Second, a significant direction in post-deployment network management is presented in Chapter 3, highlighting the emphasis on node mobility and self-healing paradigms.

The second core, first elaborates on current hindrances in WSN design and deployment, and investigates two prominent technologies that have a significant impact on our understanding and realization of WSNs. Namely, the rise of service-oriented networks, including notable work in public sensing systems, and the hype around integrating cloud-sensing paradigms toward more enabling infrastructures. The advent of IPv6 in WSN research has caused a significant stir of arguments on the trade-off of connectivity versus longevity under an Internet-driven paradigm.

Third, we highlight a significant contribution in dynamic WSN paradigms. First, we set the formal representation of resources utilized in networked sensing systems, and elaborate on their viability both in stationary and mobile environments. We thereby int...