![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction to Global Macro Hedge Funds

Joseph G. Nicholas

Founder and Chairman of HFR Group

The global macro approach to investing attempts to generate outsized positive returns by making leveraged bets on price movements in equity, currency, interest rate, and commodity markets. The macro part of the name derives from managers’ attempts to use macroeconomic principles to identify dislocations in asset prices, while the global part suggests that such dislocations are sought anywhere in the world.

The global macro hedge fund strategy has the widest mandate of all hedge fund strategies whereby managers have the ability to take positions in any market or instrument. Managers usually look to take positions that have limited downside risk and potentially large rewards, opting for either a concentrated risk-taking approach or a more diversified portfolio style of money management.

Global macro trades are classified as either outright directional, where a manager bets on discrete price movements, such as long U.S. dollar index or short Japanese bonds, or relative value, where two similar assets are paired on the long and short sides to exploit a perceived relative mispricing, such as long emerging European equities versus short U.S. equities, or long 29-year German Bunds versus short 30-year German Bunds. A macro trader’s approach to finding profitable trades is classified as either discretionary, meaning managers’ subjective opinions of market conditions lead them to the trade, or systematic, meaning a quantitative or rule-based approach is taken. Profits are derived from correctly anticipating price trends and capturing spread moves.

Generally, macro traders look for unusual price fluctuations that can be referred to as far-from-equilibrium conditions. If prices are believed to fall on a bell curve, it is only when prices move more than one standard deviation away from the mean that macro traders deem that market to present an opportunity. This usually happens when market participants’ perceptions differ widely from the actual state of underlying economic fundamentals, at which point a persistent price trend or spread move can develop. By correctly identifying when and where the market has swung furthest from equilibrium, a macro trader can profit by investing in that situation and then getting out once the imbalance has been corrected. Traditionally, timing is everything for macro traders. Because macro traders can produce significantly large gains or losses due to their use of leverage, they are often portrayed in the media as pure speculators.

Many macro traders would argue that global macroeconomic issues and variables influence all investing strategies. In that sense, macro traders can utilize their wide mandate to their advantage by moving from market to market and opportunity to opportunity in order to generate the outsized returns expected from their investor base. Some global macro managers believe that profits can and should be derived from other, seemingly unrelated investment approaches such as equity long/short, investing in distressed securities, and various arbitrage strategies. Macro traders recognize that other investment styles can be profitable in some macro environments but not others. While many specialist strategies present liquidity issues for other, more limited investing styles in charge of substantial assets, macro managers can take advantage of these occasional opportunities by seamlessly moving capital into a variety of different investment styles when warranted. The famous global macro manager George Soros once said, “I don’t play the game by a particular set of rules; I look for changes in the rules of the game.”

SUMMARY

Global macro traders are not limited to particular markets or products but are instead free of certain constraints that limit other hedge fund strategies. This allows for efficient allocation of risk capital globally to opportunities where the risk versus reward trade-off is particularly compelling. Whereas significant assets under management can prove an issue for some more focused investing styles, it is not a particular hindrance to global macro hedge funds given their flexibility and the depth and liquidity in the markets they trade. Although macro traders are often considered risky speculators due to the large swings in gains and losses that can occur from their leveraged directional bets, when viewed as a group, global macro hedge fund managers have produced superior risk-adjusted returns over time.

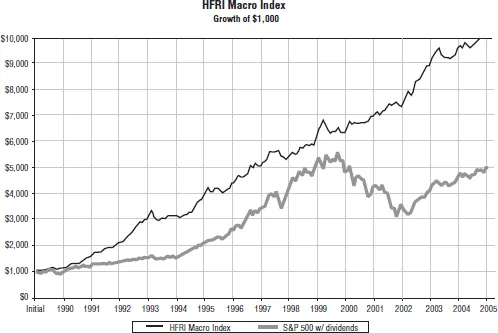

From January 1990 to December 2005, global macro hedge funds have posted an average annualized return of 15.62 percent, with an annualized standard deviation of 8.25 percent. Macro funds returned over 500 basis points more than the return generated by the S&P 500 index for the same period with more than 600 basis points less volatility. Global macro hedge funds also exhibit a low correlation to the general equity market. Since 1990, macro funds have returned a positive performance in 15 out of 16 years, with only 1994 posting a loss of 4.31 percent. (See Figure 1.1.)

In light of the correlation, volatility, and return characteristics, global macro hedge fund strategies are a welcome addition to any portfolio.

![]()

Chapter 2

The History of Global Macro Hedge Funds

The path to today’s style of global macro investing was paved by John Maynard Keynes a century ago. For an economist, Keynes was a renaissance man. Not only was he the father of modern macroeconomic theory but he also advised world governments, was involved in the Bloomsbury intellectual circle, and helped design the architecture of today’s global macroeconomic infrastructure by way of the World Bank and International Monetary Fund. At the same time, he was also a successful investor, using his own macroeconomic principles as an edge to extract profit from the markets. Some say he was the first of the modern global macro money managers.

In the words of Keynes’ biographer Robert Skidelsky, “[Keynes] was an economist; he was an investor; he was a patron of the arts and a lover of ballet. He was a speculator. He was also confidant of prime ministers. He had a civil service career. So he lived a very full life in all those ways.”

Keynes speculated with his personal account, invested on behalf of various investment and insurance trusts and even ran a college endowment, each of which had different goals, time horizons, and product mandates. Upon his death, he left a substantial personal fortune primarily a result of his financial market activities.

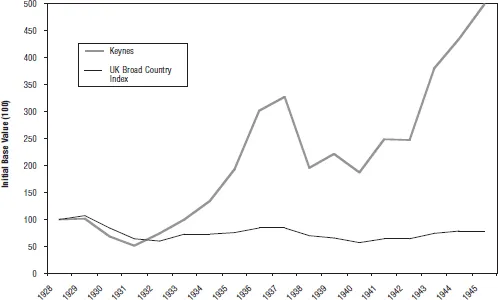

Evidence of Keynes’ investing acumen can be found in the returns of the King’s College Cambridge endowment, the College Chest, for which he had total discretion as the First Bursar. A publicly available track record shows he returned an average of 13.2 percent per annum from 1928 to 1945, a time when the broad UK equity index lost an average of 0.5 percent per annum. (See Figure 2.1.) This was quite a feat considering the 1929 stock market crash, the Great Depression, and World War II occurred over that time frame.

But, like all great investors, Keynes first had to learn some difficult lessons. He was not immune to blowups in spite of his superior intellect and understanding of global markets. In the early 1900s, he successfully speculated in global currencies on margin before switching to the commodity markets. Then, during the commodity slump of 1929, his personal account was completely wiped out by a margin call. After the 1929 setback, his greatest successes came from investing globally in equities but he continued to speculate in bonds and commodities.

Skidelsky adds, “His investment philosophy. . .changed in line with his evolving economic theories. He learned a lot of his theory from his experience as an investor and this theory in turn modified his practice as an investor.”

Keynes’ distaste of floating currencies (ironically his original vehicle of choice for speculating) eventually led him to participate in the construction of a global fixed currency regime at Bretton Woods in 1945. The post-World War II economic landscape, coupled with the ensuing Cold War–induced peace and the relative stability fostered by Bretton Woods, led to a boom in developed-country equity markets starting in 1945 and lasting until the early 1970s. During that time, there were few better opportunities in the global markets than buying and holding stocks. It wasn’t until the breakdown of the Bretton Woods Agreement in 1971, and the subsequent decline in the U.S. dollar, that the investment universe again offered the opportunities that spawned the next generation of global macro managers.

POLITICIANS AND SPECULATORS

Recent history is riddled with examples of politicians attempting to place blame on speculators for shortcomings in their own policies, and the breakdown of Bretton Woods was no exception. When the currency regime unraveled, President Nixon attempted to lay blame on speculators for “waging an all-out war on the dollar.” In truth, his own inflationary policies are more often cited as the underlying problem, with speculators a mere symptom of the problem.

THE NEXT GENERATION OF GLOBAL MACRO MANAGERS

The next round of global macro managers emerged out of the breakdown of the Bretton Woods fixed currency regime, which untethered the world’s markets. With currencies freely floating, a new dimension was added to the investment decision landscape. Exchange rate volatility was introduced while new tradable products were rapidly being developed. Prior to the breakdown of Bretton Woods, most active trading was done in the liquid equity and physical commodity markets. As such, two different streams of global macro hedge fund managers emerged out of these two worlds in parallel.

The Equity Stream

One stream of global macro hedge fund managers emerged out of the international equity trading and investing world.

Until 1971, the existing hedge funds were primarily focused on equities and modeled after the very first hedge fund started by Alfred Winslow Jones in 1949. Jones’s original structure is roughly the same as most hedge funds today: It was domiciled offshore, largely unregulated, had less than 100 investors, was capitalized with a significant amount of the manager’s money, and charged a performance fee of 20 percent. (Allegedly, the now standard 20 percent performance fee was modeled by Jones upon the example of another class of traders who demanded a profit sharing arrangement that provided the proper incentive for taking risk: Fifteenth-century Venetian merchants would receive 20 percent of the profits from their patrons upon returning from a successful voyage.)

The A.W. Jones & Co. trading strategy was designed to mitigate global macro influences on his stock picking. Jones would run an equally weighted “hedged” book of longs and shorts in an attempt to eliminate the effects of movements by the broader market (i.e., stock market beta). Once currencies became freely floating, though, a new element of risk was added to the equation for international equities. Whereas managers using the Jones model sought to neutralize global macro–induced moves, the global macro managers who emerged from the international equity arena sought to take advantage of these new opportunities. Foreign exchange risk was treated as a whole new tradable asset class, especially in the context of foreign equities where currency exposure became a major factor in performance attribution.

Managers from this stream such as George Soros, Jim Rogers, Michael Steinhardt, and eventually Julian Robertson (Tiger Management) were all too w...