eBook - ePub

Labor in America

A History

Melvyn Dubofsky, Joseph A. McCartin

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Labor in America

A History

Melvyn Dubofsky, Joseph A. McCartin

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book, designed to give a survey history of American labor from colonial times to the present, is uniquely well suited to speak to the concerns of today's teachers and students. As issues of growing inequality, stagnating incomes, declining unionization, and exacerbated job insecurity have increasingly come to define working life over the last 20 years, a new generation of students and teachers is beginning to seek to understand labor and its place and ponder seriously its future in American life. Like its predecessors, this ninth edition of our classic survey of American labor is designed to introduce readers to the subject in an engaging, accessible way.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Labor in America an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Labor in America by Melvyn Dubofsky, Joseph A. McCartin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Storia & Storia nordamericana. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Conditions of Labor in Colonial America

The development of the American colonies depended upon human labor. That labor came in a variety of forms – free, slave, bonded, skilled, unskilled, agricultural, and artisanal. In the first two and a half centuries of colonization, the area of the New World now known as the eastern United States was an overwhelmingly rural society. Especially during the colonial period (1619 to 1776), and for some time afterward, upwards of 90 percent of the people lived in the countryside. The vast majority of free people were also self-employed, either as independent farmers, artisans, or in a host of urban retail trades and professions.

From the onset, the American colonies included a number of bustling seaport cities. In the cities a real need existed for casual day laborers and hired craftsmen, both of whom were paid wages. Moreover, as the southern colonies shifted their agricultural base from the production of food crops for local consumption to cash crops (first tobacco and rice, then cotton) for sale in the world market, the need for laborers mounted.

To satisfy the rising demand for labor in a new land, potential employers turned mostly to indentured servants and enslaved Africans. For the seventeenth century and much of the eighteenth century, free independent wage laborers formed a small part of the colonial labor force. At first, indentured servants – those who signed contracts of indenture in Britain or on the Continent, and those “redemptioners” whose cost of passage to the New World was paid by their indenture (sale) at auction in their port of arrival – formed the bulk of a labor force in which waged work proved the exception. Indentured laborers worked the tobacco farms of the Chesapeake region, provided household labor on farms and in city homes in all the colonies, and engaged in all sorts of other labor for their masters and mistresses. As the southern colonies found an increasing demand for their agricultural products abroad, whether in the English metropolis, the Caribbean sugar islands, or on the European continent, indentures failed to satisfy the planters' demand for labor. The African slave trade held out a remedy. Not only did the slave trade seem to offer an endless supply of bound labor, but African slaves, unlike indentured Europeans, were bound in perpetuity and defined as chattel (property), while their children inherited their parents' bound status. The advantages that slave labor provided in comparison to indentured labor led more prosperous landowners and merchants in the northern colonies to turn to slave labor as well. Over the course of the next two centuries, as indentured labor decreased, slave labor increased.

Free workers, a minority of the total colonial labor force, included such skilled craftsmen as carpenters and masons, shipwrights and sailmakers, as well as tanners, weavers, shoemakers, tailors, smiths, coopers (barrel makers), glaziers (glass makers), and printers. A number of less skilled but also putatively free laborers found employment as carters, waterfront workers, and in other irregular forms of work. The skilled craftsmen among these workers at first plied their trades independently, but as the centers of population grew, master workmen set up small retail shops and employed journeymen who worked for wages and apprentices who offered their services in return for learning the craft. The journeymen may have earned a wage but they were not entirely free laborers; instead, they were ordinarily bound by contracts that determined their length of employment and forbade them to leave their position until full satisfaction of the contract.

By the close of the eighteenth century, these journeymen had begun to form local trade societies – the genesis of the first unions and of what was to become, in time, the organized labor movement. They did so because their interests began to clash with the goals of their masters, who had become increasingly interested in increasing their profits at the expense of their journeymen and apprentices. Masters who had once toiled alongside their apprentices and journeymen often evolved into merchant-capitalists who marketed the goods produced by their waged employees.

The simple economic pattern of those distant days bears no resemblance to the complex economy of the twenty-first century. The status of a small handful of independent artisans and mechanics has little relationship to that of the many millions of waged and salaried workers in twenty-first-century society. Certain underlying conditions, however, were operative in colonial days that would strongly influence the whole course of American labor.

From the first, the history of labor in America was affected by the availability of arable land. As long as land was abundant and European settlers could seize it from indigenous tribes of native Americans who occupied it – which was the case from the seventeenth century to the close of the nineteenth century – life for the majority tended to be salutary. Regardless of class, most New World residents enjoyed more material comforts, better health, and greater life expectancies than their Old World counterparts. That at least is the evidence as compiled by scholars who have studied and accumulated statistical data about morbidity, mortality, and body types. The abundance of land also made it more difficult for the colonial upper class to transport English feudal patterns, which required common people to defer to their social betters, to the new environment. This reality encouraged farmers, artisans, and ordinary workers to assert their own independence and equality, and to become active participants in a vigorous movement for broader democracy. No matter how much America changed in the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, white workers maintained their belief that they should be free and equal citizens in a democratic republic. Such beliefs endowed American workers and their institutions with a distinctive character.

The early settlers had no more than landed in Virginia and Massachusetts than they realized the imperative need for workers in the forest wilderness that was America. In the first voyage to Jamestown and three succeeding expeditions, the Virginia Company had sent over to the New World a motley band of adventurers, soldiers, and gentlemen. In growing despair of establishing a stable colony out of such unsatisfactory material, Captain John Smith finally entered a violent protest. “When you send again,” he wrote home emphatically, “I entreat you rather send but thirty carpenters, husbandmen, gardeners, fishermen, masons, and diggers of trees' roots, well provided, than a thousand such as we have.”

Plymouth fared better. Artisans, craftsmen, and other laborers largely made up the little band of Pilgrims, and the Bishop of London rudely characterized even their leaders as “guides fit for them, cobblers, tailors, feltmakers, and such-like trash.” Among the Puritan settlers of Massachusetts Bay in 1630 there was also a majority of artisans and tillers of the soil. In spite of this advantage, the founders of New England soon felt, as had those of Virginia, the scarcity of persons content with performing the humble tasks of society. Governor Winthrop of Massachusetts wrote despairingly in 1640 of the difficulty of keeping wage earners on the job. They were constantly moving on to frontier communities where pay was higher, or else were taking up land to become independent farmers. Cotton Mather made it “an Article of special Supplication before the Lord, that he would send a good servant.”

While tillers of the soil and “diggers of trees' roots” were a primary consideration in these early days of settlement, the demand for skilled workers rapidly mounted. The colonists were compelled to become carpenters and masons, weavers and shoemakers, whatever their background, but both on southern plantations and in New England towns, trained artisans and mechanics were always needed. In time, on southern plantations masters tutored some of their slaves in the skills of such necessary trades as carpentry, masonry, blacksmithing, and even cordwaining (shoemaking). Learning went both ways, as slaves taught masters in the South Carolina Low Country how to adopt rice-growing practices they had used on West Africa's Grain Coast. Rice production was so labor intensive that the Low Country became home to the colonies' largest plantations.

The ways in which the labor problem was met varied greatly in different parts of America. The circumstances of early settlement and natural environment led New England to rely more on free workers than indentures, while the South was ultimately to depend almost wholly on slaves from Africa. In the majority of colonies during the seventeenth century, and continuing on through the eighteenth century in the middle colonies, the bulk of the labor force was recruited from indentured servants. It is probable that at least half of all the colonists who came to the New World arrived under some form of indenture and took their place as free citizens only after working out their terms of contract.

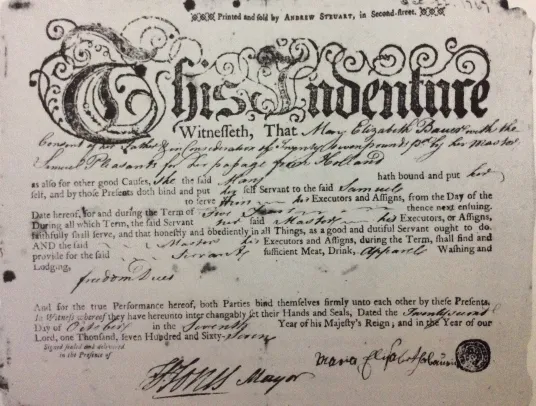

Figure 1.1 Certificate of indenture, 1767. This certificate bound one Mary Elizabeth Bauer to Samuel Pleasants for five years of labor in return for his payment of her passage to the American colonies. (Historical Society of Pennsylvania).

There were three sources for such bound labor: men, women, and children whose articles of indenture were signed before leaving the Old World; the redemptioners, or so-called free-willers, who agreed to reimburse their passage money by selling their labor after landing in the colonies; and convicts sentenced to transportation to America. Once in the colonies, these various groups coalesced into the general class of bound servants, working without wages and wholly under their masters' control for a set number of years.

So great was the demand for labor that a brisk trade developed in recruiting workers. Agents of the colonial planters and of British merchants scoured the countryside and towns of England, and somewhat later made their way to Europe, especially the war-devastated areas of the Rhineland, to advertise the advantages of emigrating to America. At country fairs they distributed handbills extravagantly describing the wonders of this new land, where food was said to drop into the mouths of the fortunate inhabitants and every man had the opportunity to own land. The promises held forth by the agents were often so glowing and enthusiastic that the poor and aspiring gladly signed articles of indenture with little realization of the possible hardships of the life upon which they were embarking. The “crimps,” agents who worked the English countryside, and the so-called “newlanders” operating on the Continent, did not hesitate at fraud and chicanery.

Thousands of persons were “spirited” out of England under these circumstances, and far from trying to prevent such practices, the local authorities often encouraged them. The common belief that England was overpopulated led them to approve heartily of the overseas transportation of paupers and vagabonds, the generally shiftless who might otherwise become a burden upon the community. Indeed, magistrates sometimes had such persons rounded up and given the choice between emigration and imprisonment. It was also found to be an easy way to take care of orphans and other minors who had no means of support; the term “kidnapping” had its origin in this harsh mode of peopling the colonies.

In 1619, the Common Council of London “appointed one hundred Children out of the swarms that swarme in the place, to be sent to Virginia to be bound as apprentices for certain yeares.” The Privy Council initially endorsed the move and authorized the Virginia Company to “imprison, punish and dispose of any of those children upon any disorder by them committed, as cause shall require; and so to Shipp them out for Virginia, with as much expedition as may stand for convenience.” Some 40 years later, the Privy Council appears to have become aroused over the abuse of this practice by the Virginia Company. Two ships lying off Gravesend were discovered to have aboard both children and other servants “deceived and inticed away Cryinge and Mourning for Redemption from their Slavery.” It was ordered that all those detained against their will should be released at once. Most often, however, the line between voluntary and involuntary transportation – especially when it involved young children and the poor – was very hard to draw.

As time went on, prisons contributed an increasing number of emigrants who crossed the Atlantic as “His Majesty's Seven-Year Passengers.” They were at first largely made up of “rogues, vagabonds and sturdy beggars” who had proved “incorrigible.” However, during the eighteenth century more serious offenses were added to the list for which transportation overseas was meted out. The prerevolutionary roster of such immigrants in one Maryland county, adding up to 655 persons and including 111 women, embraced a wide range of crimes – murder, rape, highway robbery, horse-stealing, and grand larceny. Contemporary accounts succinctly described many of the women as “lewd.”

The colonies came to resent bitterly this influx of inmates from English prisons – “abundance of them do great Mischiefs…and spoil servants, that were before very good” – and they found it increasingly difficult to control them. But in spite of these protests, the practice was continued, and in all some 50,000 convicts are believed to have been transported, largely to the middle colonies. In Maryland, a favored dumping ground, they made up the bulk of indentured servants throughout the eighteenth century.

“Our Mother knows what is best for us,” a contributor to the Pennsylvania Gazette groused in 1751. “What is a little Housebreaking, Shoplifting, or Highway-robbing; what is a son now and then corrupted and hanged, a Daughter debauched, or Pox'd, a wife stabbed, a Husband's throat cut, or a child's brains beat out with an Axe, compared with this Improvement and Well peopling of the Colonies?” Benjamin Franklin bitterly declared that the policy of “emptying their jails into our settlements is an insult and contempt the cruellest, that ever one people offered another.”

Although contemporaries and subsequent scholars emphasized the involuntary aspects of colonial immigration and the role played in the migration stream by paupers and criminals, the most recent research discloses a different reality. First, in the New World, indentured servitude largely replicated English patterns of rural employment with variations to adapt it to colonial conditions. Second, the immigration of indentured servants proved a rational response to the realities of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century markets for skilled and unskilled labor; it effectively redistributed labor from a sated English market to a hungry colonial one. Third, the indentured servants were a cross-section of the English laboring classes. As the economist David Galenson observes in his book, White Servitude in Colonial America (1981), “the indentured servants probably came in significant numbers from all levels of the broad segment of English society bounded at one end by the gentry, and at the other by the paupers.”

The first African slaves arrived in Virginia not long after the founding of the colony. At first little distinguished the status of slaves from that of indentured laborers, and the two groups often worked together, especially on the tobacco plantations of the Chesapeake and Virginia, socialized together, and even mated. While slaves lacked contracts that specified the terms and duration of their service, their future paths seemed partly open. Some slaves took advantage of the demand for labor to negotiate arrangements with their masters that allowed them to hire themselves out and accumulate savings, eventually purchasing their freedom. In the 1660s, in some areas of Virginia nearly one-third of African Americans were free people.

Over time, however, at first slowly and then more rapidly in one colony after another, lawmakers began to d...