eBook - ePub

Equitation Science

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Equitation Science

About this book

A new edition of a highly respected textbook and reference in the rapidly emerging field of equitation science. Equitation Science, 2nd Edition incorporates learning theory into ethical equine training frameworks suitable for riders of any level and for all types of equestrian activity. Written by international experts at the forefront of the development of the field, the welfare of the horse and rider safety are primary considerations throughout. This edition features a new chapter on research methods, and a companion website provides the images from the book in PowerPoint.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Introduction – The Fascination with Horses and Learning

Introduction

Everyone who spends time with horses will from time‐to‐time become fascinated by their behaviour and learning abilities. One does not have to search for long to find reports of extraordinary learning performance in individual horses; examples range from ‘Clever Hans’, the horse that appeared to be able to count and read but, even more interestingly, was responding to very subtle cues from human bystanders; to reports of horses being able to open box doors and gates (Figure 1.1), to everyday accounts of circus and sports horses performing precise movements in response to small cues from their trainers or riders (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.1 ‘Horses on the run’: In 2013, the story about Mariska hit the world press after her owner posted a YouTube video showing how Mariska could open not only her own box door but also make her way to open the doors of the other horses’ boxes.

(Photo courtesy of Sandy and Don Bonem.)

Figure 1.2 Horses can learn to respond to and differentiate between light tactile cues from their riders, regardless of the type of gear used.

(Photo courtesy of Dr. Portland Jones and Sophie Warren.)

Humans have been fascinated by animal learning for centuries and, since the 1800s, scientists from various fields have investigated the mammalian and avian brain to understand how animals of different species learn and adapt to their environments. The best‐studied species are rodents and birds, primarily because these species are easy to study and to keep in a laboratory. Despite the evolutionary differences between these species, remarkable similarities exist in the way they learn. This has resulted in the development of ‘learning theory’, a set of principles that apply to all animals and explain how animals learn. Learning theory has revolutionised the way humans think about animal training, and learning theories are applied with great success in the training of, for example, dogs, marine and other zoo animals (Figure 1.3). Indeed, it is difficult to find a modern training manual for these animals that does not use learning theory as a basis. Learning theory establishes clear guidelines and training protocols for correct training practices and methods of behaviour modification. It is truly fascinating, easy to relate to and simple to understand. Throughout this book, we will repeatedly refer to ‘learning theory’ as simply a comprehensive term for ‘the ways in which animals learn’.

Figure 1.3 Modern training manuals for many species are based on learning theory.

Similarly, more and more horse‐trainers use and teach learning theory and understand the opportunities it can offer trainers in every discipline. Like all other animals, horses learn in predictable and straightforward ways. However, traditional horse‐training differs fundamentally from the food‐based training methods used for marine mammals, exotic carnivores and most companion animals, because it largely relies on what is termed ‘negative (subtraction) reinforcement’. During their early training, horses learn that the correct response results in the reduction of pressure from the bit via the reins when they stop or slow. Pressure from the rider’s legs or spurs is reduced when the horse moves forward. To be effective and humane, the application of pressure must be subtle and its removal immediate once the horse complies. This reliance on pressure and the release of pressure underlines the need to ensure that training programmes are effective and humane. Science can and should step in to measure, analyse and interpret what we do with and to horses.

Understanding the rules of learning can help horse‐trainers work with their horses in a way that maintains the horse’s welfare as paramount. Learning theory is not necessarily an ethical theory but it helps us train horses in a way that makes it as easy as possible for the horse to respond and succeed during training. Furthermore, it allows us to avoid behavioural side effects such as fear or aggression, caused by inappropriate training.

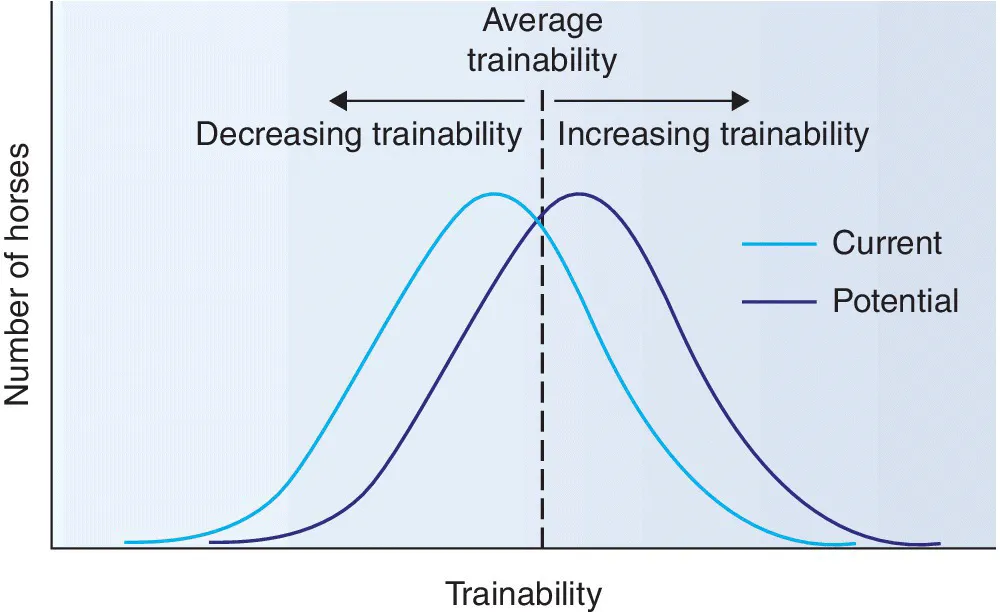

Veterinary epidemiologists, whose job it is to describe the spread and impact of disorders, often talk about wastage within a population. This is the percentage of animals or, in the case of working animals, the percentage of potential working days lost through illness or disease. Problem behaviours are the cause of much of this wastage, and in the world of the riding horse it is more significant than many of us would like to imagine (Hothersall and Casey, 2012). A global improvement in application of learning theory, particularly the timing and consistency of pressure and release, could lead to a significant increase in the number of horses considered to be trainable (Figure 1.4).

Figure 1.4 Theoretical normal distributions to show how the numbers of horses that cope with training can be increased by using more enlightened approaches.

(Reproduced from Equine Behavior, copyright Elsevier 2004.)

Horses are being confused on a very regular basis by less‐than‐ideal handling and become unusable or, worse, dangerous as a result (Hawson et al., 2010a). For example, Buckley (2007) reporting on 50 out of 84 Pony Club horses, noted that this focal sub‐set of owners reported a total of 251 misbehaviour days during a 12‐month period. Importantly, on more than half of these days, this misbehaviour was classified as dangerous enough to cause potential injury to horse and/or rider. Horse‐riding is generally considered to be more dangerous than motorcycle riding, skiing, football and rugby (Ball et al., 2007). In Australia, horse‐related injuries and death exceed those caused by any other non‐human species (domestic or otherwise) (AIHW National Injury Surveillance Unit, 2005).

Among non‐racehorses, previous studies indicate that up to 66% of euthanasia in horses between 2 and 7 years of age was not because of health disorders (Ödberg and Bouissou, 1999). The implication is that they were culled for behavioural reasons. Clearly, this level of behavioural wastage is unacceptably high. The likelihood is that many such horses are mistrusted or labelled troublesome. With their reputation for being dangerous preceding them, they are met with an escalation of tension in the reins or pressure from the rider’s legs, the very forces they have learned to fear and avoid. Difficult horses go from one home to the next and are often forced to trial new ways of escaping pressure and satisfying competing motivations.

The Scientific Approach

Science is sometimes accused of objectifying animals, but the emergence of animal welfare science has already created changes in legislation that have improved animal wellbeing. It has shown us how modern diets may prompt obsessive–compulsive disorders; how weaning can affect social relations among animals; and how the behaviour of a breed can be a product of its shape.

It is the rigour of the scientific approach that ensures that we arrive as closely as possible to the truth about horses. The scientific method sometimes seems tedious because of its insistence in dismantling the elements of the questions piece by piece and its tactic in not setting out to prove a hypothesis but to disprove the null hypothesis (the non‐existence of it). It is rather like the legal notion of innocent until proven guilty. Similarly, in science it is empty until proven full. An important tenet in behaviour science is Lloyd Morgan’s canon, which dictates that in no case should an animal activity be interpreted in terms of higher psychological processes if it can be reasonably interpreted in terms of processes that stand lower in the scale of psychological evolution and development. Occam’s razor (The Law of Parsimony) is a more general maxim that decrees that in making explanations, you should not make more assumptions than the minimum needed, so if a phenomenon can be explained in terms of simple rather than more complex ways, it is more likely to be correct. The more assumptions you have to make, the more unlikely an explanation is. This principle underpins all scientific theory building. It is easy to make rash assumption...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- About the Companion Website

- 1 Introduction – The Fascination with Horses and Learning

- 2 Ethology and Cognition

- 3 Anthropomorphism and the Human–Horse Relationship

- 4 Non-associative Learning

- 5 Associative Learning (Attractive Stimuli)

- 6 Associative Learning (Aversive Stimuli)

- 7 Applying Learning Theory

- 8 Training

- 9 Horses in Sport and Work

- 10 Apparatus

- 11 Biomechanics

- 12 Unorthodox Techniques

- 13 Stress and Fear Responses

- 14 Ethical Equitation

- 15 Research Methods in Equitation Science

- 16 The Future of Equitation Science

- Glossary of the Terms and Definitions and of Processes Associated with Equitation

- References

- Index

- End User License Agreement

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Equitation Science by Paul McGreevy,Janne Winther Christensen,Uta König von Borstel,Andrew McLean in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Equine Veterinary Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.