- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Basic Guide to Dental Radiography

About this book

Basic Guide to Dental Radiography provides an essential introduction to radiography in the dental practice. Illustrated throughout, this guide outlines and explains each topic in a clear and accessible style.

- Comprehensive coverage includes general physics, principles of image formation, digital image recording, equipment, biological effects of x-rays and legislation

- Suitable for the whole dental team

- Illustrated in full colour throughout

- Ideal for those completing mandatory CPD in radiography

- Useful study guide for the NEBDN Certificate in Dental Radiography, the National Certificate in Radiography or the Level 3 Diploma in Dental Nursing

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

General physics

ATOMS AND MOLECULES

Whenever setting out on a project of this type, it is difficult to know what to use as your starting point.

Let us start by looking at what makes up the world as we know it.

We look around and see lakes, mountains, fields, etc., but what if we could look into these things and see what makes them what they are?

We would see atoms and molecules.

There can’t be many people who have not heard of these, but what are they?

Atoms and molecules are linked to elements and compounds (here is the problem – almost every time we mention anything, it will lead us straight to something else we need to know).

Elements are single chemical substances such as oxygen, hydrogen, sulphur, etc. We can take a large amount of an element and keep cutting it down to make it smaller and smaller, but there is a limit to how small we can make it.

We come to a point where all that we have is a single atom of the substance; if we then cut it to an even smaller size, we will be breaking down the atom, and it will no longer be that particular substance.

- Atoms are the smallest particle of an element that can exist and still behave as that element.

Breaking down an atom eventually produces just a collection of the bits that make up the atom.

Here we go again! What is smaller than an atom? Or what are atoms made of?

There are many so‐called fundamental particles that make up the atoms that provide the basic building blocks for all of the things that we see, touch and know of. Some of these fundamental particles are only now being discovered.

For the purposes of fulfilling the basic guide brief, we will concentrate on only three types of particle: protons, neutrons and electrons.

Protons and neutrons are large (that’s relative; remember we would need very powerful microscope to see even these particles), and electrons are small.

To represent the difference in these particles in a way you can visualise, think of placing a single grape pip on the ground and then standing a person 6 ft tall next to it.

The grape pip represents the size of an electron, and the 6‐ft‐tall person the size of a proton or a neutron. Protons and neutrons are slightly different in size, but for our purposes they can be considered to be the same, but electrons are 1840 times smaller than either of the other two particles.

The protons and electrons each have an electrical charge and these charges are of opposite poles (like the two ends of a battery). The protons have a positive charge (+ve), and the electrons a negative charge (−ve).

Despite the relative size difference of the particles, the two charges, although opposite poles (or signs), are of equal size or strength.

So the positive charge on one large proton is completely cancelled out by the negative charge on one tiny electron.

Neutrons have no charge at all (they are neutral).

How do these particles fit together to make an atom?

Figure 1.1 shows what has become an accepted idea of the appearance of an atom.

Figure 1.1 Classic basic model for the structure of the atom

There is a large central nucleus, containing protons and neutrons with the electrons circling in a number of orbits at different distances from the nucleus. These orbits have traditionally been called electron shells or energy shells.

This model will be adequate for our understanding, but do remember that the electron orbits are not all in the same plane. The atom is three‐dimensional, and the electron orbits taken all together would make a pattern much more like looking at a football.

This makes sense if you think of the electron orbits as actual shells; they completely surround the nucleus much like the layers of an onion. This is difficult to demonstrate on a flat page, and we have become used to the picture as shown (Figure 1.1) with lots of circles having the same centre.

The number of protons in the nucleus tells us what sort of atom it is. A nucleus containing 6 protons would be a carbon nucleus, 11 protons sodium, and 82 protons lead. The number of protons present is the atomic number of the element and of course of the atom; the number of protons in fact tells us what chemical substance the atom is.

The protons in the nucleus all have a positive charge, and the tendency for positive charges is to push each other apart just like two magnetic north or two south poles would. They need something to keep them from pushing each other away; this function is performed by the neutrons. The neutrons don’t do this job alone, but for the purposes of this particular text, we need look no further into nuclear forces. At very low atomic numbers, there will be equal numbers of protons and neutrons; however as atomic number increases, the higher concentration of positively charged protons needs a higher number of neutrons to overcome the forces of repulsion between them.

The number of electrons in each orbit is specific and is determined by the following formula:

where E is the number of electrons and n is the number of the electron shell.

So, the closest shell to the nucleus is number 1. In that shell, you can have 2 × 12 electrons.

12 is 1 × 1 so that 1 multiplied by 2 tells us we can have two electrons in the first shell.

In the second shell we can have 2 × 22. So 2 × 2 (n2) = 4 multiplied by 2 gives 8.

In the third shell 2 × 32 gives 2 × 9. So 18 electrons would be allowed in shell 3.

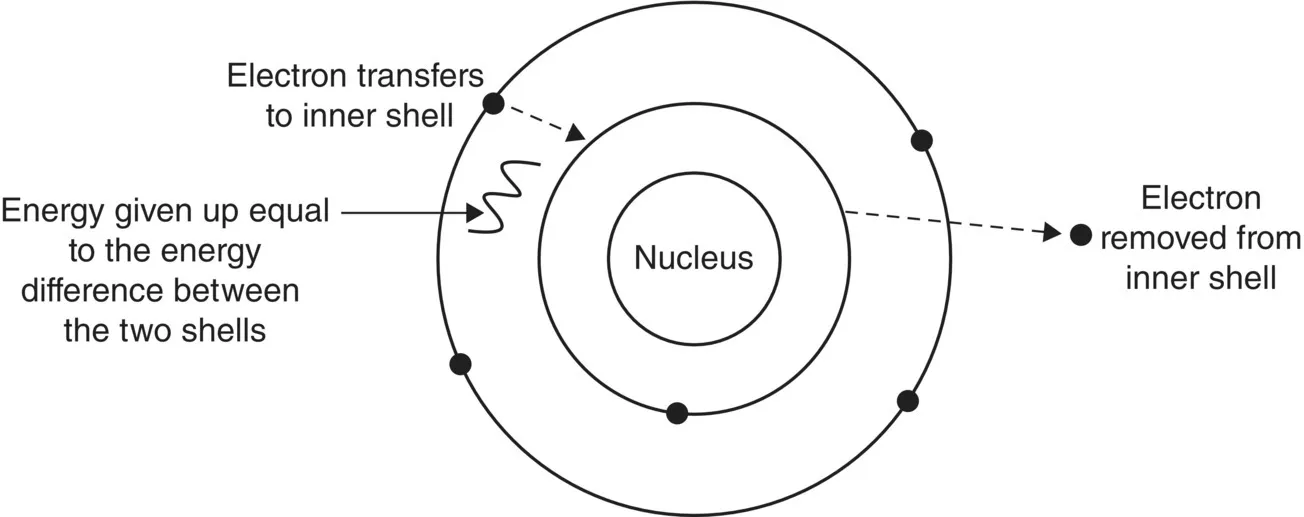

No electrons can be positioned in shell 2 if shell 1 is not full and none in shell 3 if shell 2 is not full. That is to say that all inner shells must be filled before outer shells can contain any electrons. If an electron were removed from an inner shell, then one would move down from an outer shell to fill the gap. (This becomes important when we consider the effects of exposure to radiation.)

The process works like this because atoms always exist in their lowest energy state (ground state) and inner shell electrons are the low energy ones. So if we take out a low‐energy inner shell electron, the atom is at a higher level of energy than it could be, so an electron from a shell further out falls to fill the gap and in the process gives up some of its energy.

The electron filling the gap will give up some energy because it can only be in the lower shell if it has the correct level of energy. This process will continue until the exchange takes place at the outermost shell of the atom. There will then be an electron space free in the outer shell of the atom (the one that is the greatest distance from the nucleus) (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 Redistribution of electrons to the atoms’ lowest energy state

From the previous descriptions, it is clear that most of the mass of an atom (it’s easier to think of this as weight or ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter 1: General physics

- Chapter 2: X‐ray production

- Chapter 3: X‐ray interaction with matter

- Chapter 4: Principles of image formation

- Chapter 5: Imaging with dental X‐ray film

- Chapter 6: Digital imaging recording

- Chapter 7: X‐ray equipment

- Chapter 8: Radiation doses and dose measurement

- Chapter 9: Biological effects of X-rays

- Chapter 10: Legislation: Ionising Radiations Regulations 1999 (IRR 1999)

- Chapter 11: Legislation: Ionising Radiation (Medical Exposures) Regulations 2000 (IR(ME)R 2000), Statutory Instrument 1059

- Chapter 12: Quality assurance

- Chapter 13: Dental intra‐oral paralleling techniques

- Chapter 14: Orthopantomography

- Chapter 15: Other dental radiographic techniques

- Appendix A: Adequate training

- Appendix B: Image quality troubleshooting

- Index

- End User License Agreement

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Basic Guide to Dental Radiography by Tim Reynolds in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Dentistry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.