eBook - ePub

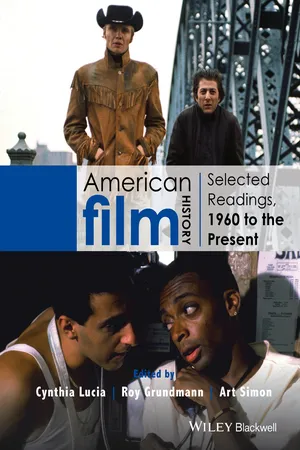

American Film History

Selected Readings, 1960 to the Present

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

American Film History

Selected Readings, 1960 to the Present

About this book

From the American underground film to the blockbuster superhero, this authoritative collection of introductory and specialized readings explores the core issues and developments in American cinematic history during the second half of the twentieth-century through the present day.

- Considers essential subjects that have shaped the American film industry—from the impact of television and CGI to the rise of independent and underground film; from the impact of the civil rights, feminist and LGBT movements to that of 9/11.

- Features a student-friendly structure dividing coverage into the periods 1960-1975, 1976-1990, and 1991 to the present day, each of which opens with an historical overview

- Brings together a rich and varied selection of contributions by established film scholars, combining broad historical, social, and political contexts with detailed analysis of individual films, including Midnight Cowboy, Nashville, Cat Ballou, Chicago, Back to the Future, Killer of Sheep, Daughters of the Dust, Nothing But a Man, Ali, Easy Rider, The Conversation, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, Longtime Companion, The Matrix, The War Tapes, the Batman films, and selected avant-garde and documentary films, among many others.

- Additional online resources, such as sample syllabi, which include suggested readings and filmographies, for both general and specialized courses, will be available online.

- May be used alongside American Film History: Selected Readings, Origins to 1960 to provide an authoritative study of American cinema from its earliest days through the new millennium

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access American Film History by Cynthia Lucia, Roy Grundmann, Art Simon, Cynthia Lucia,Art Simon,Roy Grundmann, Cynthia Lucia, Art Simon, Roy Grundmann in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film History & Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

1960–1975

1

Setting the Stage

American Film History, 1960–1975

Profound changes rocked American cinema in the second half of the twentieth century, many of which reflected new directions in the history of the nation. A number of these developments occurred or, at least, got under way in the 1960s. By mid-decade, the anxiety that American society had initially kept at bay through a spirit of hope and renewal fully came to the fore, and forces of social and moral cohesion rapidly gave way to tendencies of questioning and confusion. From social rebellion and economic inequality there emerged an impulse toward cultural experimentation that also affected American films, but that, in the late 1970s and 1980s, would give way again to more conservative tendencies, as American politics shifted to the right and the US film industry reconsolidated and eventually reorganized itself on a global scale.

Film Industry Decline and Transformation

The old studio system of five majors (MGM, RKO, Warner Bros., Paramount, and Twentieth Century-Fox), vertically integrated with their own theaters guaranteeing certain exhibition of their films, and three minor studios that did not own theaters (Columbia, Universal, United Artists) had been in place for over 30 years. By the early 1960s this system was largely defunct, its remnants subject to a series of mergers, acquisitions, and restructurings that would install a new generation of leaders at the top of the industry. Their predecessors, the legendary moguls, had run Hollywood as the nation's main purveyor of mass entertainment by defining movie-going as first and foremost a family affair. The new crop faced a dramatically shrinking audience base resulting from demographic shifts brought on by suburbanization and a widening generation gap. During the 1960s, when the nuclear family grew less stable, the industry survived, in part, by targeting the youth market, while not losing sight, for a time at least, of its general audience. And while the relative stability of the classical era had yielded long tenures for studio bosses, enabling them to impart their artistic imprimatur, from the 1960s forward, heads of production became cogs within sprawling corporate structures. In this climate, the rare producers able to flourish long enough to develop a creative oeuvre were semi-independent makers of B-movies, like Roger Corman, and, more recently, writer-director-producers epitomized by Steven Spielberg, whose tycoon status signals a different order of independence.

Hollywood in the 1960s not only found itself in search of a product and an audience, but the industry was also saddled with growing doubt as to how American it indeed was. By 1966, 30 percent of American films were independently produced and 50 percent were so-called runaway productions – films made in Italy, Spain, and other European countries that beckoned with cheap, non-unionized labor. By that time, also, the effects of the 1948 Paramount Decree, which forced the studios to divest their ownership of theaters, loosened Hollywood's stranglehold on the domestic market. Beginning in the 1950s, exhibitors' burgeoning independence had opened the door to foreign imports. Between 1958 and 1968, the number of foreign films in US distribution would gradually exceed the number of domestic productions (Cook 2004, 427). While in 1955 television was Hollywood's only serious competitor on the media market, ten years later American viewers had an unprecedented array of choices. They could buy a movie ticket to The Sound of Music or stay home and watch the Ed Sullivan Show; they could (fairly easily) see François Truffaut's Jules and Jim (1963) or seek out numerous other examples of what would become known as the golden age of European art cinema – or, starting in the mid-1960s, they could catch the rising tide of third world films. If they were not keen on reading subtitles, their options included artistically ambitious independent films by such directors as John Cassavetes or quirky, independently made horror and exploitation flicks by the likes of George A. Romero and Russ Meyer. Or they could seek out innovative documentaries made in direct cinema style, or avant-garde films like Andy Warhol's The Chelsea Girls (1966), which had made the leap from urban underground venues and college film societies into commercial exhibition.

In order to minimize risk, studios began to strike international financing deals that shifted their role to co-producer or distributor of internationally made films, exposing the industry to a wave of foreign talent and new artistic influences. Filmmakers like John Schlesinger and Roman Polanski would parlay their new wave cachet into international careers and relocate to the US. Others, like Michelangelo Antonioni and UK-based American expatriate Stanley Kubrick, directed projects that, while financed by Hollywood, were shot overseas. A new generation of American directors, including Arthur Penn, Sidney Lumet, and John Frankenheimer, who had come from television and also were attuned to foreign film, would also help broaden the aesthetics of American films to a significant degree. The so-called “movie brats” of the late 1960s and early 1970s, the first generation of directors trained in film school, including Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, and Brian De Palma, would extend this trend.

By the early 1970s, Hollywood had assimilated stylistic elements from numerous outside sources. The pre-credit sequence it took from television. The long take – while already present in 1940s prestige productions and 1950s widescreen cinema – was extended further through emerging auteurs influenced by European art cinema, independent documentaries, and the avant-garde. These cinemas also helped trigger the opposite trend in Hollywood – the acceleration of cutting and the fragmentation of the image into split screens, multiple slivers (showcased in the credit sequence of The Thomas Crown Affair, 1968), or collage-type arrays (as featured in the famous “Pusher Man” sequence from the 1972 blaxploitation film Superfly). Finally, the prominence of new wave cinemas inspired a loosening of Hollywood continuity editing conventions. Individualists like Sam Peckinpah, who pioneered slow motion, and Hal Ashby, who popularized the use of telephoto lenses, further broadened the formal palette of studio releases.

When Hollywood staged a return to classical topics and treatments during the Reagan era, some of these devices would be toned down. What ultimately characterizes the era from the late 1960s to the present, however, is the studios' openness to using most any formal and narrative technique, provided it can be placed in the service of contemporary Hollywood storytelling. Since the 1990s, especially, the increased accessibility of filmmaking equipment (brought about by the digital revolution), the diversification of exhibition outlets (generated by the internet and convergence culture), and the emergence of new generations of auteurs (like Steven Soderbergh, Gus Van Sant, Baz Luhrmann, Todd Haynes, Joss Whedon, and Guillermo del Toro, who work on a global scale and cross over between big studio and indie productions, as well as between film and television) have generated a more elastic, globalized film aesthetic for a youth audience weaned on graphic novels, YouTube, and cellphone movies.

Cold War Anxiety

Even before the emergence of the late 1960s counterculture and its wide-ranging critique of American institutions, filmmakers challenged the long-standing political consensus that had underwritten the Cold War.1 After over half a century in which the movies had lent their support to American military campaigns, celebrating the GIs and the officers who led them, a cluster of films released between 1962 and 1964 no longer marched in step with the Pentagon. Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964) and Fail-Safe (1964) told essentially the same story, the former through black humor and the latter through straight drama. Both questioned the hydrogen bomb as a peacekeeping device and argued that the technology of destruction threatened humanity's power to control it. Although Fail-Safe ended with a powerfully frightening montage of freeze frames showing people on the streets just before nuclear detonation – vividly illustrating a population at the mercy of the nuclear age – it was Dr. Strangelove's absurdist satire and its eerily incongruent ending – as bombs explode to the song “We'll Meet Again” – that would resonate for decades after its release. Here, citizens are totally absent as the buffoons in charge of their safety channel their own sexual fears and fantasies into a race toward the apocalypse. Seven Days in May (1964) imagined a coup d'état planned within the Joint Chiefs to stop the President on the verge of signing a treaty with the Soviets. Even more shocking, if ideologically less coherent, as R. Barton Palmer argues in Volume I of this series, was The Manchurian Candidate (1962), a returning veteran story at its cruelest, in which Raymond Shaw, falsely decorated a Korean War hero, is brainwashed to become a communist assassin. Caught in the crossfire between Red China and the US, sacrificed by his power hungry mother, and forced to kill his wife, Shaw embodies the myriad suicidal and twisted psycho-sexual impulses woven into Cold War thinking.

Gender Roles and Sexual Mores in Early 1960s Hollywood

During the 1960s, the movies' representation of gender and sexuality underwent dramatic changes, particularly in regard to Hollywood's portrayal of women. Initially, however, change seemed slow to come, as Hollywood's star machinery reflected 1950s ideals of beauty and morality. The reigning box office star from 1959 to 1963 was Doris Day, whose persona in a string of popular, old-fashioned comedies combined Cold War ideals of feminine virtue and propriety with increasingly progressive attitudes towards female independence. In contrast to the best screwball comedies of the 1930s, in which a man and a woman meet, fall in love, separate, and then “remarry” as true equals, in Day's films marriage was not merely the default mode of heterosexual partnership. It became the idealized goal of her protagonists who, in their mid- to late thirties, were afraid of missing the boat that would carry them into the connubial haven of motherhood and domesticity. Glossy Madison Avenue settings in Pillow Talk (1959) and That Touch of Mink (1961) function as a backdrop for Day's smartly coutured female professionals, as she conveys her characters' conflicted feelings about acting on or reining in her carnal desires with comic verve – all indicative of pressure on Hollywood to acknowledge, however timidly, American women's increasing sexual agency.

Fear of female sexual independence also played itself out in a number of early 1960s dramas about prostitutes: the Hollywood prestige film Butterfield 8 (1960) starring Elizabeth Taylor, the quirky overseas production Never on Sunday (1960) shot by grey-listed Hollywood director Jules Dassin, and two of Billy Wilder's satirical comedies, Irma La ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- The Editors

- Title page

- Copyright

- Acknowledgments

- Preface

- Part I 1960–1975

- Part II 1976–1990

- Part III 1991 to the Present

- Index

- EULA