Handbook of Safety Principles

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Handbook of Safety Principles

About this book

Presents recent breakthroughs in the theory, methods, and applications of safety and risk analysis for safety engineers, risk analysts, and policy makers

Safety principles are paramount to addressing structured handling of safety concerns in all technological systems. This handbook captures and discusses the multitude of safety principles in a practical and applicable manner. It is organized by five overarching categories of safety principles: Safety Reserves; Information and Control; Demonstrability; Optimization; and Organizational Principles and Practices. With a focus on the structured treatment of a large number of safety principles relevant to all related fields, each chapter defines the principle in question and discusses its application as well as how it relates to other principles and terms. This treatment includes the history, the underlying theory, and the limitations and criticism of the principle. Several chapters also problematize and critically discuss the very concept of a safety principle. The book treats issues such as: What are safety principles and what roles do they have? What kinds of safety principles are there? When, if ever, should rules and principles be disobeyed? How do safety principles relate to the law; what is the status of principles in different domains? The book also features:

• Insights from leading international experts on safety and reliability

• Real-world applications and case studies including systems usability, verification and validation, human reliability, and safety barriers

• Different taxonomies for how safety principles are categorized

• Breakthroughs in safety and risk science that can significantly change, improve, and inform important practical decisions

• A structured treatment of safety principles relevant to numerous disciplines and application areas in industry and other sectors of society

• Comprehensive and practical coverage of the multitude of safety principles including maintenance optimization, substitution, safety automation, risk communication, precautionary approaches, non-quantitative safety analysis, safety culture, and many others

The Handbook of Safety Principles is an ideal reference and resource for professionals engaged in risk and safety analysis and research. This book is also appropriate as a graduate and PhD-level textbook for courses in risk and safety analysis, reliability, safety engineering, and risk management offered within mathematics, operations research, and engineering departments.

NIKLAS MÖLLER, PhD, is Associate Professor at the Royal Institute of Technology in Sweden. The author of approximately 20 international journal articles, Dr. Möller's research interests include the philosophy of risk, metaethics, philosophy of science, and epistemology.

SVEN OVE HANSSON, PhD, is Professor of Philosophy at the Royal Institute of Technology. He has authored over 300 articles in international journals and is a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Engineering Sciences. Dr. Hansson is also a Topical Editor for the Wiley Encyclopedia of Operations Research and Management Science.

JAN-ERIK HOLMBERG, PhD, is Senior Consultant at Risk Pilot AB and Adjunct Professor of Probabilistic Riskand Safety Analysis at the Royal Institute of Technology. Dr. Holmberg received his PhD in Applied Mathematics from Helsinki University of Technology in 1997.

CARL ROLLENHAGEN, PhD, is Adjunct Professor of Risk and Safety at the Royal Institute of Technology. Dr. Rollenhagen has performed extensive research in the field of human factors and MTO (Man, Technology, and Organization) with a specific emphasis on safety culture and climate, event investigation methods, and organizational safety assessment.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

1

Introduction

1.1 Competition, Overlap, and Conflicts

1.2 A New Level in the Study of Safety Principles

1.3 Metaprinciples of Safety

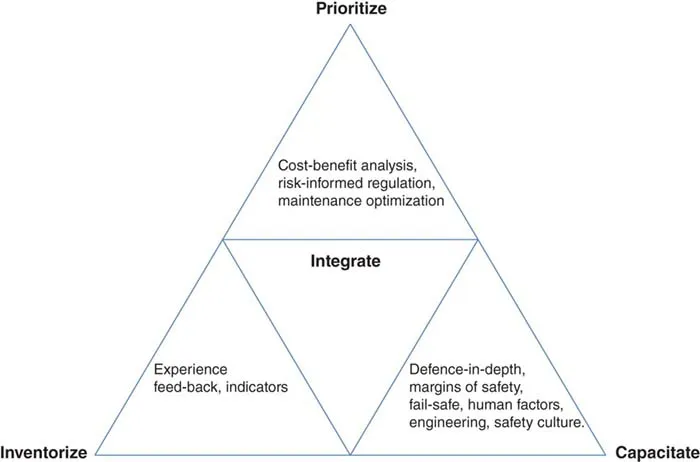

- Inventorize. Identify and assess specific safety problems in planned or existing systems.

- Capacitate. Investigate what capacities the system has to deal with safety-related problems and how those capacities can be improved. Many of these principles are applied in the design phase but can also be implemented as a consequence of applying problem-finding principles in existing systems.

- Prioritize. Set priorities among the potential improvements.

- Integrate. Make safety management coherent and comprehensive, for example, by using general quality principles and integrated safety management principles.

Table of contents

- Cover

- Operations Research and Management Science

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Preface

- List of Contributors

- 1: Introduction

- 2: Preview

- Part I: Safety Reserves

- Part II: Information and Control

- Part III: Demonstrability

- Part IV: Optimization

- Part V: Organizational Principles and Practices

- Index

- EULA